Somewhere inbetween ghosts and demagoguery—or, what to do now there is now no such thing as “Unitarianism”

|

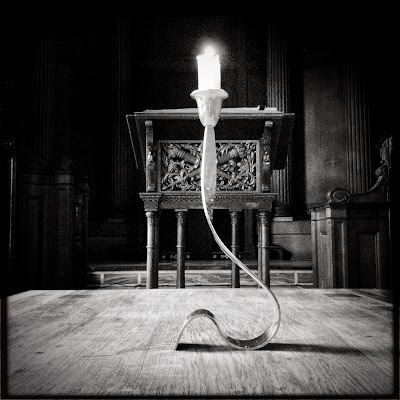

| Lit candle in the Cambridge Unitarian Church, Emmanuel Road |

The Five Points of Calvinism which both Universalists such as John Murray (1741-1815) and Unitarians such as James Freeman Clarke (1810-1888) rejected are often known by the acronym: T.U.L.I.P.

TOTAL DEPRAVITY : Because of the fall, man is unable of himself savingly to believe the gospel.

UNCONDITIONAL ELECTION : God’s choice of certain individuals unto salvation before the foundation of the world rested solely in His own sovereign will.

LIMITED ATONEMENT : Christ’s redeeming work was intended to save the elect only and actually secured salvation them. His death was a substitutionary endurance of the penalty of sin in the place of certain specified sinners.

IRRESISTIBLE GRACE : In addition to the outward general call to salvation which is made to everyone who hears the gospel, the Holy Spirit extends to the elect a special inward call that inevitably brings them to salvation.

PERSEVERANCE OF THE SAINTS : All who were chosen by God, redeemed by Christ, and given faith by the Spirit are eternally saved. They are kept in faith by the power of Almighty God and thus persevere to the end.

It was this kind of pernicious and cruel theology that we, as a liberal church tradition, have consistently opposed; a opposition most famously summed up by Alfred S. Cole who, in his Our Liberal Heritage, famously imagined the spirit of the times (the zeitgeist) saying to the English Universalist John Murray:

“Go out into the highways and by-ways of America, your new country. . . . You may possess only a small light, but uncover it, let it shine, use it in order to bring more light and understanding to the hearts and minds of men and women. Give them, not hell, but hope and courage. Do not push them deeper into their theological despair, but preach the kindness and everlasting love of God.”

—o0o—

From “A Theology of Personal and Societal Transformation: The Bicentennial Legacy of James Freeman Clarke” by Paul S. Johnson (Minns Lectures 2010)

In his history, The Unitarians and the Universalists, David Robinson asserts that James Freeman Clarke (1810-1888) was “one of the most important churchmen in nineteenth century Unitarianism and may be thought of as the most representative figure among the Unitarian clergy and leadership.” (Robinson, 1985, p. 234)

[. . .]

In 1886 Clarke published a series of essays under the title of Vexed Questions in Theology. The lead essay, The Five Points of Calvinism and the Five Points of the New Theology, contained the five points of Unitarianism for which he is principally remembered. Clarke begins the essay by naming the five points of Calvinism . . .

[. . .]

Revolving around the ideas of sin and salvation, these doctrines omit, claimed Clarke, the principle truths Jesus taught—“love to God, love to man, forgiveness of enemies, purity of heart and life, faith, hope, peace, resignation, temperance, and goodness.” Truer to Jesus’ teaching are the five new points he suggests: the fatherhood of God, the brotherhood of man, the leadership of Jesus, salvation by character, and the continuity of human development in all worlds, or the progress of mankind onward and upward forever. These five points, which Clarke hoped would become the basis for a universal religion encapsulate what he had preached and written in his forty-three year ministerial career and thus are very good way of presenting his underlying theology and then relating them to contemporary Unitarian Universalism.

—o0o—

ADDRESS

Somewhere inbetween ghosts and demagoguery—or, what to do now there is now no such thing as “Unitarianism”

One of the consequences of being asked to write and record the early Sunday morning reflections for BBC Radio Cambridgeshire this month in five, two-and-a-half minute pieces was how it forced me to think clearly about what positive, unequivocal philosophical religion or religious philosophy I, personally, would like to pass on to anyone listening. I realized that it could only be a modern version of the philosophical approach first offered to the world in Athens some 2,000 years ago by Epicurus and then Lucretius. For those interested in hearing or reading what I’ve been saying, you can do that here.

Now, you may wonder, why am I not bringing this message to you today? Well, it’s because the opportunity to write and present these talks had another consequence in that it helped me further clarify the basic difference that exists between the personal rôle I temporarily have on the radio this month and the week to week, year to year public rôle I have here as your minister.

Whether rightly or wrongly, here on a Sunday morning, I have no mandate to offer you only my own preferred philosophical religion or religious philosophy; instead I am required to do something different, something quite unlike that required of ministers in other church settings.

To help understand just exactly what this “something different” is one needs firstly to see that until the early twentieth century things were not as they are now. Then — were Unitarians allowed by the BBC to broadcast, which we were not — the philosophical religion or religious philosophy I would have offered people on the radio would have been exactly the same as that which I offered you week by week from this lectern. This was because then there existed, more or less, something distinctive that could meaningfully be labelled “Unitarianism” — a liberal Protestant, Christian theology which promoted what its adherents believed were the truth and consequences flowing from the unity of an essentially loving God displayed, primarily and most perfectly, in the example of the fully human Jesus.

It’s important to remember that, although our denomination has always refused to adopt creedal statements of belief it has, at times, been happy to use guiding catechisms and/or general statements of belief and the most commonly adopted such statement both in the UK and the US at the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries was James Freeman Clarke’s very influential “Five Points of the New Theology” which were often framed and hung up in prominent positions in our churches.

This fact serves as a reminder that, until some ninety to a hundred years ago, a person would only become a Unitarian minister and/or join a Unitarian congregation in so far as they already subscribed — albeit completely freely and with a clean conscience — to this commonly held Unitarian denominational position, this “Unitarianism”. If you chose to join a Unitarian church you did so wanting, expecting, to hear this kind of theology preached to you week by week on a Sunday; you wanted the Five Points of the New Theology, you most certainly did not want the horrors of TULIP because you wanted not hell, but hope and courage. In short you wanted Unitarianism and Universalism and not Calvinism.

So, to return to my earlier point if, as a Unitarian minister, you were ever invited on to BBC radio to give a series of Sunday morning reflections you would have known exactly what positive, unequivocal philosophical religion or religious philosophy you wanted to pass on to the world and it was going to be the same one you offered your congregation in church later on that same day — it was Unitarianism — a religion concerned to speak about the fatherhood of God, the brotherhood of man, the leadership of Jesus, salvation by character, and the continuity of human development in all worlds or the progress of mankind onward and upward forever.

To be sure arguments were still had in the denomination over various theological details and emphases, and there were occasionally some more serious theological disputes but, in general, there existed a shared faith which was believed to help a person lead a good life and die a good death and able to say all along the way, as Martin Luther was reputed to have said, “Here I stand, I can do no other.” It was a religious faith — an “-ism” — which you wanted confidently to share with the wider world.

But this thing which could meaningfully be called “Unitarianism” received the first of two mortal blows, during the First World War. Think about it, given that during this conflict the total number of military and civilian casualties was about 40 million, Freeman Clarke’s five points began to strike more and more people as being hopelessly naïve and fatally flawed. Belief in the liberal Christian, loving kind of supernatural God which was needed to underpin Freeman Clarke’s five points was becoming increasingly untenable and Epicurus’ ancient and famous set of questions began to strike powerfully home once again:

“Is God willing to prevent evil, but not able? Then he is not omnipotent. Is he able, but not willing? Then he is malevolent. Is he both able and willing? Then whence cometh evil? Is he neither able nor willing? Then why call him God?”

The different, but intimately related, horror that was the Second World War, with its concentration-camps and nuclear weapons, dealt the second mortal blow to anything that could be called classic “Unitarianism”.

What followed was a slow but inevitable theological fragmentation in which individual ministers, members of congregations and whole congregations were each forced to try and pick up the pieces as best they could from the liberal theological wreckage of the two-world wars and put something together that was felt to be at least half-workable.

I ought to point out here that this was just as true for all other liberal protestant, Christian churches, not just our own Unitarian ones. Conservative churches had, of course, an easier time than we all did because, remember, they still had TULIP to fall back on and, underpinned as it was by a strong belief in a malevolent and brutally judgemental God, they could interpret the two world wars as being God’s just judgement upon humankind’s total depravity. But how could, how would, we liberals interpret it? Could this interpretation be done through a continued belief in and proclamation of an essentially loving God and the Five Points of the New Theology? Whatever you feel should or could have been the case, the historically arrived at answer has proven to be “No”.

Anyway, all this means that since 1945 no minister, no individual member, and no congregation connected with the name Unitarian, has been able to avoid dealing with the consequences of this situation and, at present, I see three ways forward currently being attempted.

The first is an approach which acquiesces to the fragmentary state of affairs but which simultaneously claims there exists — or can exist — a kind of new-age, inter-faith inspired universalist religious approach in which all the diverse and fragmentary religions and philosophies will be shown in truth to be ONE. It is no coincidence that, at present — and not without considerable controversy among us — more and more people calling themselves “inter-faith ministers” are seeking formal positions with Unitarian congregations.

The second is to adopt some clear, narrower doctrinal philosophical stance of some sort or another. Not surprisingly, where this is attempted, for the most part, it turns out to be the current personal religious philosophy or philosophical religion of the present minister. The spectrum of such stances runs from, at one end, to the re-adoption of a clearly defined liberal Christianity (including versions of classic Unitarianism) and, at the other end of the spectrum, to the adoption of avowedly non-religious, secular approaches akin to those found in groups such as the Sunday Assembly.

Clearly both of these approaches have their advocates and, to their supporters they will no doubt, seem to have their clear advantages. Personally, I don’t find either approach at all appealing because, in their different ways, both these options seem to me to be seeking to reintroduce something they hope will become the “new-Unitarianism”. However, I am so suspicious of all collective -isms that I’m fairly certain I will go to my grave trying to subvert them all. They seem to me to be very, very dangerous things. But, as always, in the conversation which follows this address and the musical offering, you are perfectly free to disagree with me about this . . .

However, it is this opening up of my comments to disagreement and critique that brings me to a third and way of dealing with the disappearance of classic Unitarianism which doesn’t, I hope, fall into becoming an -ism and which, for good or ill, is the one being tried here.

It is a project which is designed to do two things simultaneously which are, quite deliberately, in permanent and sometimes seemingly contradictory tension. To talk in American university terms the project here attempts to offer the congregation something in which “to minor”, and something in which “to major”.

So, firstly, here’s that in which we “minor”.

This church community tries to offer a person some of the, thankfully, still serviceable critical and skeptical philosophical and religious ideas and tools left intact in the wreckage of post-war Unitarianism with which that same person can freely begin to hone a confident philosophical and religious position which they can hold with a clean heart and full pathos and which can ground their attempts to lead a good and meaningful life. Naturally, what this personal philosophical and religious position eventually turns out to be is going to differ from person to person and I hope, you have have found, or be on the way to finding, your own.

But, from the point of view of the public rôle of this church and my duty to it as minister, all these vital, actualized, personal philosophical and religious positions (including my own deeply held one that I am speaking about on the radio) are “the minor” subject, they are secondary to what it is we “major in” together.

This is because, in addition to helping each other to find a satisfactory personal philosophical and religious position, we are simultaneously engaging in the somtimes seemingly contradictory attempt to help each other also to commit to becoming men and women without fixed, final positions, becoming people who truly understand the supreme value of the freedom to be tomorrow what we are not today. Here we are together trying to become men and women ever open to what Henry David Thoreau called the “The newer testament — the Gospel according to this moment”. In other words here, together, we are majoring in becoming appropriately free spirits who have understood the supreme value of being able to change our mind if and when the evidence shows this to be necessary. This includes — of course — even being able to change our minds about our current philosophical and religious positions we’ve spent years honing.

Here, together, we learn that to be a completely unconditioned free spirit, never stopping anywhere at anytime to take a stand on any of important issues of our own day, is to be nothing more than an ineffectual ghost. Here, together, we also learn that to be a person dogmatically and uncritically committed only and forever to this or that -ism (whatever it is and no matter how carefully and rationally arrived at) is to be little more than on the way to demagoguery.

In this pleasant garden, somewhere in between ghosts and demagogues, here we try to grow the strange and rare free spirits which are the hoped-for fruit of the modest project underway here. What’s going on here is not, and cannot be, any kind of -ism — not even a new Unitarianism — but it can, and maybe even will, help you to find a firm enough personal faith which, to paraphrase the poet Mary Oliver, you can hold against your bones knowing your life depends upon it but which, when the time comes to let it go, you can let it go, let it go.

POSTSCRIPT

I tackle this same subject in a more systematic and extended way in my talk for the Sea of Faith conference in 2016 which you can find at the following link:

Comments