Some personal reflections on the twentieth anniversary of the events of September 11th, 2001

A recorded version of the following piece can be found at this link

On Tuesday, September 11th 2001, I was just over a year into my ministry at the Cambridge Unitarian Church. I was working in my study on the church premises (where I am recording this today) and had just stopped to make a cup of tea after my lunch. I turned on the radio to listen to the 2pm news to find that both towers of the World Trade Center had been hit by aircraft and were ablaze. Not surprisingly, like everyone else, I was truly shocked by what I was hearing, so shocked in fact that I knew I needed both human company and to see myself whether this was really happening. Since my wife, Susanna, was at work and we did not have a television I left my study and went a few hundred yards down the road to an Italian café called “Savino’s” where the coffee was (and is) good, where they had a television, and where I knew I’d find some people wth whom I could speak. I ordered my coffee while I, and everyone else in the small room, stared up uncomprehendingly at the events unfolding on TV. I stayed there for a couple of hours watching the horror until I knew Susanna would be back from work when I went home to be with her as she tried to contact her sister who lived in New York only a few blocks from the Twin Towers to check she had not been hurt. Thankfully she had not been hurt physically but, like many New York residents, it’s true to say she’s never fully recovered from that day’s events.

The day had a big impact on my own life because until that moment very few people in British culture were even vaguely interested in my own field of expertise in religion and theology. Then, all of a sudden, the things about which I knew most became of interest to everyone. In the years which followed I found myself involved in all kinds of formal and informal conversations, meetings, conferences and courses, all of which were concerned to understand how and why religion was again seriously, and often violently, impacting on the world’s politics and our everyday lives. The most striking and memorable event for me was being asked in 2007 to chair a one-day conference at the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst, co-sponsored by NATO and the British International Studies Association (BISA), on the subject of “Engaging with Religion for Building Peace: The Experience of Afghanistan and Iraq.”

Anyway, here we are, today, on the twentieth anniversary of the attacks on the Twin Towers and the Pentagon which has come immediately after the Taliban’s recapture of Afghanistan following the chaotic US and British withdrawal from the country during the latter days of August. To say it’s a bloody mess would be the height of understatement and, speaking frankly, I can only look upon what has happened, and is happening, as expressing yet another monumental failure on the part of the so-called western liberal democracies.

It seems to me that during the intervening twenty years we have learnt very little, almost nothing. One thing we have clearly not learnt is that the number of victims of these attacks is far, far greater than the 2,996 people who died on the day but must include the hundreds and hundreds of thousands of innocent people killed in the wars launched in Afghanistan and Iraq and in the other violent interventions perpetrated by Osama Bin Laden, Ayman al-Zawahiri, George Bush Jr and Tony Blair in the years which followed.

What can someone like me say. Very little, of course, almost nothing. But the twentieth anniversary of the attacks on New York makes me feel I should try to say something useful and, on reflection, I have decided that what I said to my own congregation in Cambridge on the tenth anniversary can simply be restated today because it contains something of the very little I feel I have learnt following that dreadful day twenty years ago.

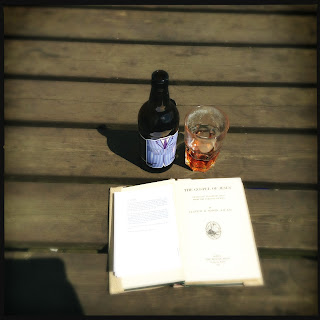

But, before I begin I want you to be aware that throughout I use the terms “9/11” and the “11th September 2001” to refer to very different things. At no point do I use them synonymously. Also, all the pictures to which I refer can be seen in my blogpost version of this talk, a link to which you can find in the episode notes.

—o0o—

“‘…how everything turns away / Quite leisurely from the disaster…’ — On the need not to talk about 9/11”

An address first given in the Cambridge Unitarian Church on September 12th, 2011.

I tried very hard to resist the pressure to speak today about “9/11” but as you all know there was no escape from it this week thanks to the many hours and countless column inches devoted to it in the media. To this one must add the plain and simple truth that for many reasons the events of that day influenced me profoundly and contributed to a major change of emphasis in my own personal political, religious and emotional way of being-in-the-world. Given these factors not to say something today about “9/11” seemed, in the end, to be odd and counter-productive.

On the other hand I still felt a very strong desire not to talk about the matter. By this I do not mean I wished merely to ignore “9/11” but rather I wanted to find a way to make it clear that I was actively NOT talking about it and to freight this act with useful meaning.

To help me explain why I feel the need to do this I want to introduce a distinction between “9/11” and the “11th September 2001.” Thanks to an ongoing post-hoc analysis “9/11” is now the name, a proper noun, which refers to the increasingly complex story (or stories) that have grown up in the shadow of the event of the “11th September 2001.” This is not to say that this process is an [entirely] bad thing and, at its best, and when it is not merely trying to create politically expedient myths (expedient either for the USA, its allies or its enemies — real or invented), the process of turning the catastrophe into a story can help all of us find understanding, healing and acceptance.

In a book called “Young Men and Fire”, the author Norman Maclean (best known for his story “A River Runs Through It”) tried to do this about the death of thirteen Forest Service Smoke-jumpers in Mann Gulch, Montana, on 5 August 1949. The book was a product of his strong belief that “in this cockeyed world there are shapes and designs” and he felt that “if only we have some curiosity, training, and compassion and take care [also] not to lie or to be sentimental” (Maclean p. 37) then we could reveal these same shapes and designs which allowed the living to remember creatively and unsentimentally and, thereby, learn how to continue to live better and more hopefully in the days to come.

Maclean felt that:

“If a storyteller thinks enough of storytelling to regard it as a calling, unlike a historian, he must follow compassion wherever it leads him. He must be able to accompany his characters, even into the smoke and fire, and bear witness to what they thought and felt even when they themselves no longer knew. This story of the Mann Gulch fire will not end until it feels able to walk the final distance to the crosses with those who for the time being are blotted out by smoke. They were young and did not leave much behind them and need someone to remember them” (Maclean p. 102).

It strikes me that what is true of the young men who died in the Mann Gulch fire remains true of the nearly 3,000 men and women who died on the “11th September 2001” . However, I fear that the story of the whole — that is to say the story called “9/11” — has largely been co-opted by our culture for less than honourable and healing ends.

Anyway, if you want to hear about “9/11” then I simply refer you to the many politicians and cultural commentators whose words you have heard this week and will be hearing more of during the coming days, weeks and years.

But today I want to draw your attention to the day the “11th September 2001” which in a key, even fundamental respect was a day like any other. I want to do this because I think it is important to make visible a general background without which we can all too easily develop a dangerous sense of human power and control — the same sense of power and control that made possible both the events of “9/11” and which continue to cause conflict around the world. Perhaps more importantly I want to do it so that when I conclude we can simply rest silently together in non-partisan human solidarity with those who died.

But how to show you this background, this “11th September 2001”, when every memory, every picture, every piece of footage, every witness’ story of the day is by now so coloured by “9/11”? I admit that it is hard and I’m not sure I can do it but even if I succeed in giving you the briefest and most fleeting glimpse of it today then this will be sufficient.

Probably wisely, Hoepker did not feel it was appropriate to publish his photo in 2001 and it was only in 2006 that it appeared in a book and not surprisingly it quickly became a cause of controversy. As Jones tells us:

“The critic and columnist Frank Rich wrote about it in the New York Times. He saw in this undeniably troubling picture an allegory of America’s failure to learn any deep lessons from that tragic day, to change or reform as a nation: ‘The young people in Mr Hoepker’s photo aren’t necessarily callous. They’re just American.’”

However, as Jones notes,

“Rich’s view of the picture was instantly disputed. Walter Sipser, identifying himself as the guy in shades at the right of the picture, said he and his girlfriend, apparently sunbathing on a wall, were in fact ‘in a profound state of shock and disbelief.’ Hoepker, they both complained, had photographed them without permission in a way that misrepresented their feelings and behaviour.”

If nothing else this reveals the important truth that one cannot photograph a feeling. But another important thing of which Jones reminds us is that this was the only photograph taken that day which seems “to assert the art of the photographer.”

Jones notes that

“ . . . among hundreds of devastating pictures, by amateurs as well as professionals, that horrify and transfix us because they record the details of a crime that outstripped imagination — even Osama bin Laden dared not expect such a result — this one stands out as a more ironic, distanced, and therefore artful, image. Perhaps the real reason Hoepker sat on it at the time was because it would be egotistical to assert his own cunning as an artist in the midst of mass slaughter.”

But ten years on [and now, of course, now as I record it twenty years on] it is precisely this artistic distance that counts and which helps us glimpse something that is most certainly not the egotistical cunning of an artist. This “something” is, paradoxically, the strange closeness to the “11th September 2011” [rather than “9/11” that] the picture affords us.

In his article, Jones begins to help us to see/feel this by reminding us of the famous Renaissance painting by Pieter Bruegel, “The Fall of Icarus”, in which he depicts a peasant ploughing also seemingly untroubled on as Icarus falls into the sea to his death. This painting, along with W. H. Auden’s poem “Musée des Beaux Arts” which references it, “captures something that is true of all historical moments: life does not stop dead because a battle or an act of terror is happening nearby.”

“Musée des Beaux Arts”

About suffering they were never wrong,

The Old Masters; how well, they understood

Its human position; how it takes place

While someone else is eating or opening a window or just

walking dully along;

How, when the aged are reverently, passionately waiting

For the miraculous birth, there always must be

Children who did not specially want it to happen, skating

On a pond at the edge of the wood:

They never forgot

That even the dreadful martyrdom must run its course

Anyhow in a corner, some untidy spot

Where the dogs go on with their doggy life and the torturer’s horse

Scratches its innocent behind on a tree.

In Breughel’s Icarus, for instance: how everything turns away

Quite leisurely from the disaster; the ploughman may

Have heard the splash, the forsaken cry,

But for him it was not an important failure; the sun shone

As it had to on the white legs disappearing into the green

Water; and the expensive delicate ship that must have seen

Something amazing, a boy falling out of the sky,

had somewhere to get to and sailed calmly on.

Hoepker’s picture shows us this same truth in the visual imagery of our own age, an age in which most of us are not ploughmen but men and women whose daily work includes the possibility of taking a break in the sun by a river with friends. Like the Breughel’s ploughman, as Jones says, “The people in this photograph cannot help being alive, and showing it.”

Hoepker’s and Breughel’s picture, and Auden’s and Jones’ words shockingly (if artfully) remind us that we live in a world that in its immediate and constant unfolding is beyond any simple static human knowing and to be living is to be beyond the possibility of stopping before any event, fact or thing with our minds filled with a complete knowledge of what is going on and then to [adopt a] pose that future generations might deem appropriate. To be sure after the event we can always analyse, interpret, create healing stories or dangerous myths about these events (and these will say something meaningful to us) but we must never forget that all these activities are always undertaken against a general background of radical not-knowing and against a knowledge that, despite this, we cannot help but being alive and showing it. Is this not what was shown by all of us on the “11th September 2001” in one way or another?

“9/11” on the other hand tries, understandably, to explain, to regain some power and control over the events. This [act], inevitably, distances us from the 3,000 people who died for they most certainly did not understand, they did not have any power or control.

However, the “11th September 2001” — made accessible [to us] by Hoepker’s photo and its artistic distance — brings us, paradoxically, closer to those 3,000 people and the utter incomprehension, powerlessness and horror they felt [than almost any other picture I know]. An incomprehension, powerlessness and horror that we, too, in our own ways, also felt.

With these thoughts in mind it now behoves us to consider what we are to do as we stop sometime on this day to remember and pay respect to the dead.

Are we to remember “9/11” or the “11th September 2001”?

Are we to remember what our culture tells us the day meant and means, or are we to remember and stand in solidarity with the ordinary men and women who were doing ordinary things and in which we also acknowledge a basic aspect of the human condition, that we cannot help being alive and showing it — even in the face of such a [terrible event]?

Comments