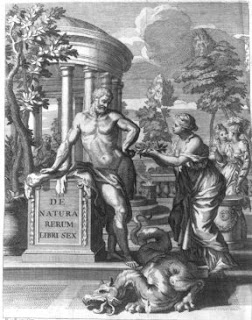

Nature's gifts are simple . . . the simple pleasures of friends stretched out on a grassy knoll (De Rerum Natura, Bk. 2)

This week I want to begin with two observations. The first is the round of continuing bad news on the financial front. I mention it because I don't think any of us can get away from it. Not to speak of it would be, not so much like avoiding the elephant in the room, but the herd of elephants trashing the room. I know it is preying on the minds of many of us and getting a lot of us down and this means, I think, that how we might respond to it continues to be worth addressing in this religious context.

This week I want to begin with two observations. The first is the round of continuing bad news on the financial front. I mention it because I don't think any of us can get away from it. Not to speak of it would be, not so much like avoiding the elephant in the room, but the herd of elephants trashing the room. I know it is preying on the minds of many of us and getting a lot of us down and this means, I think, that how we might respond to it continues to be worth addressing in this religious context.Which point brings me to my second observation, namely the coming of Spring. The flowers and blossom are coming out and are a wonderful boost to morale and our general sense of well-being. Today I'm going to suggest that a certain kind of practical meditation on Nature is going to be hugely helpful to us.

But, especially in liberal religious circles, there is a very danger in pointing to Spring and the natural world for 'help' and inspiration because, even when it sounds lovely and appealing, it can easily turn out to be no more than a mere whistling in the wind. Many liberal sermons on Nature are no more than a turning aside from the major and problematic issues of the day to a purely romantic ideal. Religion becomes merely hedonistic flower-sniffing and far from a coherent, practical philosophy. I think I have told you the story of a profoundly frustrating meeting I had to attend at which was being discussed a new collection of prayers and meditations which contained a lot (and I mean a lot) of nature poetry and natural imagery. The convenor - an insightful and gentle man by the name of Dr Beverly Littlepage - finally lost his patience in this sea of flowers and assorted greenery and uttered out loud, "Look, we've counted all the daffodils now, so can we do something more useful instead."

So yes, let us by all means look at the natural world (something Jesus constantly encouraged us to do even though his conclusions about what this showed were, in significant respects, almost certainly radically different from those I think it shows) but this looking must go on to say something or better still, show something, substantive that is more than merely a temporary calming response to our troubles. Epicurus sets us off in the right direction in one of his preserved sayings, no.12:

It is impossible for someone ignorant about the nature of the universe but still suspicious about the subjects of the myths to dissolve his feelings of fear about the most important matters. So it is impossible to receive unmixed pleasures without knowing natural science.

This is not to say anything hopelessly hubristic but, as I noted a few weeks ago it is, in the modern context (i.e. not Epicurus' Greece), to say that although our study of nature does not tell us precisely what she is, when pressed tenaciously enough, she does sometimes tell us clearly what she is not. What she has told us she is not allows us to suggest that Epicurus' practical four-part cure remains a good practical model we can still follow, namely, that studying Nature we can see that we neither need to fear God/the gods nor death; that the necessary goods of life are easy to obtain; and that the evils of life are easy to endure. These four things being played out, of course, against the background of his three goods which are to do this in the company of friends, whilst developing a certain kind of self-sufficiency and to live an analysed life.

It is against this backdrop that I now offer you, as an antidote to the gloom and doom of the times, a lovely and practical thing you can do. It is taken from Lucretius' glorious poem De Rerum Natura (The Nature of Things) which is a poetical exposition of Epicurus' philosophy:

We all know that the body's needs are modest and few: it wants not to suffer pain and it likes things that feel good. Nature's gifts are simple. She does not care for fancy decorations, gilded torcheres in the shape of human arms that light long corridors that lead to grand salons where nightly revels take place. She does not delight in elaborate gewgaws, garnitures of silver and gold, or panelled crossbeams overhead that resound from the plucked strings of the lyre. She has no need to improve on the simple pleasures of friends stretched out on a grassy knoll beneath the arching branches of living trees near water purling in some brook. What riches can equal that? Let it be spring when the weather is perfect and flowers bloom, punctuating the meadow with various colours. The body's aches and fevers flee no quicker on purple couches in tapestried chambers than under a poor man's ragged blanket.

Bk II line, 220ff - trans. David R. Slavitt

Epicurus and Lucretius are suggesting (and I agree with them) that the plain truth of the matter is that all the deepest and most real pleasures and delights we can have as human beings are available to us only when we consciously gather amongst friends who, after a long reflection on the workings of natural world, become ever more happy and secure in their sense of absolute belonging to the natural world and who begin to delight in all its workings - come rain or shine. It should be clear that is as true in times of economic growth (even when it was as distorted as were the last twenty years) as it is in times of very serious contraction. The cure is always available in the world, through the world.

But one of the traditional responses religion makes in troubled times is to point to a supposed world beyond the natural and physical - to that which is meta-natural, i.e. meta-physical. I may once have been able (or thought I was able) to do something along these lines but, after long reflection I realise I cannot any longer so I will leave such speculations to you as individuals. But what I can do is call us back into this life - whatever its difficulties - and to say clearly that we must work our hardest at making it as good as it can be. This isn't to say that there is only a miserable grinding away to be had but rather it is to say that we must learn to enjoy again properly to enjoy the transient pleasures of life as they present themselves and to enjoy them with care, attention, gentleness and respect for other's enjoyment and the long-term health of our planet.

It is a call to come back to the earth and this means going out into Nature and, in a disciplined way becoming ever more deeply mindful of it as it presents itself to us and then to take time to interpret our place within it. Today I'm suggesting that, over the next few weeks, you take time to lie down on a grassy knoll somewhere with a friend (whether husband or wife, lover or purely platonic friend), say by the river at Grantchester, and to converse with each other about the truth that there is nothing better or more pleasurable in the world than this.

But remember this is not an merely an asinine suggestion just to go out into Nature and have a nice day. I'm saying that when you do it with the right attitude the answer to the problem of life is to be found in this contemplation and one's fear of myths (whether of religion or a certain kind of economics) disappears and the possibility of true pleasure returns.

Comments

However the other approach, to insist on "Nature red in tooth and claw" is also flawed.

So the Epicurean response that you advocate makes much more sense in that it is balanced - like Emerson's ideas about polarity, or the Taoist concept of Yin and Yang. It is the dynamic balance of nature that we must emulate and contemplate, not just wax lyrical about the daffodils.