Evolution Sunday - Anecdote of a Jar

This Sunday marks the sixth annual Evolution Weekend the ongoing goal of which is, as it's founder the biologist Michael Zimmerman notes, "to elevate the quality of the discussion on this critical topic, and to show that religion and science are not adversaries. Rather, they look at the natural world from quite different perspectives and ask, and answer, different questions." It is a project I'm am very pleased to be supporting once again.

Now although Zimmerman's statement seems to us to be a fairly straightforward and uncontroversial statement, in truth, so much is hidden within it that it is worth taking the time to take a closer look. When we do we see, I think, something not only of general interest but also something which can help us bring about a much needed change in the way we look at, see, and live in the world.

Mention of 'the world' brings us to a topic that is often explored on this day namely its creation and when we hear this we tend straight-away to think that this must be to talk about the creation of all the material stuff out of which our world is made. But today I'm not interested in rehearsing any of the standard issues and controversies relating to creation and creationism. Instead, I want to look at another way in which the world is created for us and which is at least as important to us as living, breathing human-beings as is the physical/material creation that usually gets talked about. It is the creation of the world of practices into which we are thrown from birth and which always-already shapes our being-in-the-world and how we may, as we discover new scientific information about the world, create new worlds of practices more consonant with our changed understanding and knowledge.

But that this kind of creation has occurred is hard to see simply because, as a common way of putting it goes, we are rather like fish who, swimming in water, simply do not notice it is there.

But we are different from fish in that we do have the capacity to notice we are shaped by our environment - both physical and cultural - and that once we notice this we can, to some extent, change our world - or at least how we see, understand and live in our world. This means that, in principle at least, that though at times in our history we get trapped and damaged by old world-views we can find ways to access new and potentially more flourishing visions through which we may better fulfil our human potential. Key to this is the development of at least two interconnected things.

The first, is to develop ways by which we might take care regularly to notice the water through which we are currently swimming. Here, some kind of mindfulness practice is vital and that's something we try to do in the evening service. Perhaps, we should be doing it in the morning too . . .

The second, is then to find modest practical responses to what we have seen so that we may actually help slowly to transform our view of the world and, together, begin to create a new, more healthy one that we feel would be appropriate to let recede into the background and become, by degrees, simply the new clear and healthy water through which we swim.

A homely glimpse of kind of thing we need to be doing can be found in Wallace Stevens' poem 'Anecdote of a Jar.' What follows is, of course, simply my reading of the poem - assisted by the work of Dreyfus and Kelly in 'All Things Shining' - and it is important to remember that other people have understood the poem differently.

I placed a jar in Tennessee,

And round it was, upon a hill.

It made the slovenly wilderness

Surround that hill.

The wilderness rose up to it,

And sprawled around, no longer wild.

The jar was round upon the ground

And tall and of a port in air.

It took dominion every where.

The jar was grey and bare.

It did not give of bird or bush,

Like nothing else in Tennessee.

So let's look closely at what might be going on. First of all you need to remember that Stevens' seems to want to show us what the process of creating a new world *looks* like, i.e. not a creation of a new physical world but simply a new world of practices.

Stevens' genius is in seeing a number of things. The first is that he saw we can't use something so new that it makes absolutely no sense to us. So, for example, if he had decided to place on that Tennessee hill a 'schrubel-fink-hurt-mandelikon' (I've just made that up of course!) we'd all shake our heads in frustrated puzzlement at this nonsense no-thing - that is if we could recognise a 'schrubel-fink-hurt-mandelikon' in the first place! If we did this then we'd just be written off as a madman and women.

The second thing he saw was that neither could we place upon the hill something that has too much current meaning for us in our culture. So, for example, if he had placed a church upon that hill in Tennessee it would have brought with it far, far, too much of the old world to affect the kind of radical change he wants to show us we can bring about. Such things must now be edged to the margins.

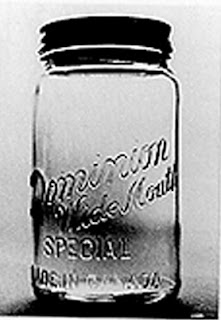

Stevens' seems to have seen that, instead, we need to use something which we still recognise in our culture but which is for us, at present, marginal, surprising and odd. However, for all that, it is important that the resonances which the idea/object carries with it are ones we think should be more valued and central than they are in our own present culture. We now know Stevens chooses a jar. Now why he might have made that apparently odd choice we'll get to in a moment. In all likelihood the jar was a screw-top preserving-jar made by a company called 'Dominion', a fact which allows a felicitous pun to be made which we'll come to in a moment.

So now Stevens does this very odd thing indeed - he places the jar on a hill in Tennessee. Tennessee I take to be an expression of the realm of our existent everyday culture and practices. The placing of the jar in this context (this world of everyday practices - Tennessee) way makes us notice - or perhaps better, creates in us a way of seeing this landscape in a new way. The jar gathers the whole landscape in a new way - it makes the slovenly wilderness surround that hill and, lo, it is suddenly ordered differently.

I think Steven's use of the pejorative adjective 'slovenly' is important. Alone, 'wilderness', often carries with it a strong sense of something positive, natural, untainted pure and uplifting. But by adding the adjective 'slovenly' to it Stevens' seems to succeed in articulating the condition many of us feel our modern culture to be in, i.e. a somewhat disordered cultural landscape of isolation, disorder and anomie and, what is worse, one which we have come to feel has often been created by our own slovenly lack of care and engagement.

So, the placing of the jar firstly reveals for us (and allows us to talk about) the condition we are in. But that is, thankfully, only the beginning of the process for the jar, now standing there, 'tall and of a port in air', begins a gathering up of the disordered, slovenly wildness and, in the light of the jar, a new order of understanding begins to appear. I take 'a port of air' to speak of the calm ordered air inside the jar as opposed to the wild and unpredictable winds that surround it on the hilltop. The jar functions, therefore, as a port in the air just as a coastal port functions in relation to the open and rough sea. It is, therefore, a strong symbol of new calm and order that has, importantly Stevens and us, no old metaphysical baggage and, because of this the jar is 'grey and bare'.

Anyway - in the light of this new grey and bare symbol of order and calm taken from the margins of our culture and now placed in a central position - the slovenly wilderness 'rises up' in our eyes with a new meaning, role and purpose and is no longer wild nor slovenly - we begin to see the world and its ordering differently, under a new aspect. This 'new' understanding also begins to spread out into the wider world - it 'sprawls around' Stevens' says because, as we know, the process of a wider cultural re-ordering is always a one which can take many centuries fully to play out.

This re-ordering Stevens now says 'takes dominion everywhere.' The pun is, it seems, upon the name of the jar itself and it is a very felicitous one because it resonates with an aspect of our language that still seems essential to us as human beings, namely 'god' language. Here's what I mean.

Stevens' concludes his poem by noting that the jar "did not give of bird or bush,/Like nothing else in Tennessee." I take this to mean that Stevens can see that the jar, so oddly brought in from the margins and suddenly placed at the centre of our world, becomes something not quite like other natural things in the world, like birds and bushes. Standing there, gray and bare, it does not speak to us - does not give - in the same way that beings like birds or bushes do. In a rather Heideggarian and non-religious sense the jar becomes a placeholder for that mysterious groundless creativity we have been used to call god and, in 'god' language, such a god has dominion over the whole world (as does a new paradigm).

To conclude - remember Stevens' jar is not itself that which will gather a new world, instead it simply stands as a sort of blueprint of what we need to do to help bring about a new world. The question for us as a contemporary liberal religious community that knows the old ways and old God of monotheism no longer works, is what is the thing or things we might bring in from the margins of our culture and make central so as to gather up our world differently and more healthily? What might be for us the jar? What might be for us the 'god' that takes dominion everywhere and which can properly replace our old bankrupt concepts of God?

APPENDIX

Additional things noted by people in the period of conversation which immediately follows the address and the musical offering:

1. The need to ensure that with any ordering there remains some space for mystery.

2. Tennessee is mountainous so putting the jar on a *hill* is to put something odd in an odd place that most Tennesseans would not even notice as some kind of upland.

3. It was humorously noted that the Dominion jar (at least the one in the picture on the order of service) was made in Canada - what might it mean to place a Canadian jar on a US hill!.

4. It is like any landscape painting - when you notice a person in a landscape that pulls the picture together.

5. A couple of people just hated the poem and, in so far as they felt they understood it, thought it was wrong-headed.

6. I had the lid on but one person thought that this made it too closed. I had in mind something Heidegger said in his Der Spiegel interview about needing a god to save us. Such a god - it seems to me - needed to be imperturbable like Epicurus' understanding of the gods (that's why I had the lid on) but, at the same time, had to be able to be seen through, transparent (again, like Epicurus' gods - who could not in a physical way causally effect the world), so that our view of the natural world could clearly be seen for what it is (that's why I took it to be a glass jar).

7. Lastly one person reminded us that the famous Scopes trial took place in Tennessee in 1925 when a high school biology teacher, John Scopes, was accused of violating the state's Butler Act that made it unlawful to teach evolution. This trial took place, of course, two years after the publication of Harmonium, the collection in which 'Anecdote of a Jar' was published. However, this unexpected resonance with a famous event concerned with the theory of evolution and its often unwelcome reception in religious circles, seemed an appropriate place to pause.

So, lots of thoughts that just carried on being expressed for another hour over coffee.

Now although Zimmerman's statement seems to us to be a fairly straightforward and uncontroversial statement, in truth, so much is hidden within it that it is worth taking the time to take a closer look. When we do we see, I think, something not only of general interest but also something which can help us bring about a much needed change in the way we look at, see, and live in the world.

Mention of 'the world' brings us to a topic that is often explored on this day namely its creation and when we hear this we tend straight-away to think that this must be to talk about the creation of all the material stuff out of which our world is made. But today I'm not interested in rehearsing any of the standard issues and controversies relating to creation and creationism. Instead, I want to look at another way in which the world is created for us and which is at least as important to us as living, breathing human-beings as is the physical/material creation that usually gets talked about. It is the creation of the world of practices into which we are thrown from birth and which always-already shapes our being-in-the-world and how we may, as we discover new scientific information about the world, create new worlds of practices more consonant with our changed understanding and knowledge.

But that this kind of creation has occurred is hard to see simply because, as a common way of putting it goes, we are rather like fish who, swimming in water, simply do not notice it is there.

But we are different from fish in that we do have the capacity to notice we are shaped by our environment - both physical and cultural - and that once we notice this we can, to some extent, change our world - or at least how we see, understand and live in our world. This means that, in principle at least, that though at times in our history we get trapped and damaged by old world-views we can find ways to access new and potentially more flourishing visions through which we may better fulfil our human potential. Key to this is the development of at least two interconnected things.

The first, is to develop ways by which we might take care regularly to notice the water through which we are currently swimming. Here, some kind of mindfulness practice is vital and that's something we try to do in the evening service. Perhaps, we should be doing it in the morning too . . .

The second, is then to find modest practical responses to what we have seen so that we may actually help slowly to transform our view of the world and, together, begin to create a new, more healthy one that we feel would be appropriate to let recede into the background and become, by degrees, simply the new clear and healthy water through which we swim.

A homely glimpse of kind of thing we need to be doing can be found in Wallace Stevens' poem 'Anecdote of a Jar.' What follows is, of course, simply my reading of the poem - assisted by the work of Dreyfus and Kelly in 'All Things Shining' - and it is important to remember that other people have understood the poem differently.

I placed a jar in Tennessee,

And round it was, upon a hill.

It made the slovenly wilderness

Surround that hill.

The wilderness rose up to it,

And sprawled around, no longer wild.

The jar was round upon the ground

And tall and of a port in air.

It took dominion every where.

The jar was grey and bare.

It did not give of bird or bush,

Like nothing else in Tennessee.

So let's look closely at what might be going on. First of all you need to remember that Stevens' seems to want to show us what the process of creating a new world *looks* like, i.e. not a creation of a new physical world but simply a new world of practices.

Stevens' genius is in seeing a number of things. The first is that he saw we can't use something so new that it makes absolutely no sense to us. So, for example, if he had decided to place on that Tennessee hill a 'schrubel-fink-hurt-mandelikon' (I've just made that up of course!) we'd all shake our heads in frustrated puzzlement at this nonsense no-thing - that is if we could recognise a 'schrubel-fink-hurt-mandelikon' in the first place! If we did this then we'd just be written off as a madman and women.

The second thing he saw was that neither could we place upon the hill something that has too much current meaning for us in our culture. So, for example, if he had placed a church upon that hill in Tennessee it would have brought with it far, far, too much of the old world to affect the kind of radical change he wants to show us we can bring about. Such things must now be edged to the margins.

Stevens' seems to have seen that, instead, we need to use something which we still recognise in our culture but which is for us, at present, marginal, surprising and odd. However, for all that, it is important that the resonances which the idea/object carries with it are ones we think should be more valued and central than they are in our own present culture. We now know Stevens chooses a jar. Now why he might have made that apparently odd choice we'll get to in a moment. In all likelihood the jar was a screw-top preserving-jar made by a company called 'Dominion', a fact which allows a felicitous pun to be made which we'll come to in a moment.

So now Stevens does this very odd thing indeed - he places the jar on a hill in Tennessee. Tennessee I take to be an expression of the realm of our existent everyday culture and practices. The placing of the jar in this context (this world of everyday practices - Tennessee) way makes us notice - or perhaps better, creates in us a way of seeing this landscape in a new way. The jar gathers the whole landscape in a new way - it makes the slovenly wilderness surround that hill and, lo, it is suddenly ordered differently.

I think Steven's use of the pejorative adjective 'slovenly' is important. Alone, 'wilderness', often carries with it a strong sense of something positive, natural, untainted pure and uplifting. But by adding the adjective 'slovenly' to it Stevens' seems to succeed in articulating the condition many of us feel our modern culture to be in, i.e. a somewhat disordered cultural landscape of isolation, disorder and anomie and, what is worse, one which we have come to feel has often been created by our own slovenly lack of care and engagement.

So, the placing of the jar firstly reveals for us (and allows us to talk about) the condition we are in. But that is, thankfully, only the beginning of the process for the jar, now standing there, 'tall and of a port in air', begins a gathering up of the disordered, slovenly wildness and, in the light of the jar, a new order of understanding begins to appear. I take 'a port of air' to speak of the calm ordered air inside the jar as opposed to the wild and unpredictable winds that surround it on the hilltop. The jar functions, therefore, as a port in the air just as a coastal port functions in relation to the open and rough sea. It is, therefore, a strong symbol of new calm and order that has, importantly Stevens and us, no old metaphysical baggage and, because of this the jar is 'grey and bare'.

Anyway - in the light of this new grey and bare symbol of order and calm taken from the margins of our culture and now placed in a central position - the slovenly wilderness 'rises up' in our eyes with a new meaning, role and purpose and is no longer wild nor slovenly - we begin to see the world and its ordering differently, under a new aspect. This 'new' understanding also begins to spread out into the wider world - it 'sprawls around' Stevens' says because, as we know, the process of a wider cultural re-ordering is always a one which can take many centuries fully to play out.

This re-ordering Stevens now says 'takes dominion everywhere.' The pun is, it seems, upon the name of the jar itself and it is a very felicitous one because it resonates with an aspect of our language that still seems essential to us as human beings, namely 'god' language. Here's what I mean.

Stevens' concludes his poem by noting that the jar "did not give of bird or bush,/Like nothing else in Tennessee." I take this to mean that Stevens can see that the jar, so oddly brought in from the margins and suddenly placed at the centre of our world, becomes something not quite like other natural things in the world, like birds and bushes. Standing there, gray and bare, it does not speak to us - does not give - in the same way that beings like birds or bushes do. In a rather Heideggarian and non-religious sense the jar becomes a placeholder for that mysterious groundless creativity we have been used to call god and, in 'god' language, such a god has dominion over the whole world (as does a new paradigm).

To conclude - remember Stevens' jar is not itself that which will gather a new world, instead it simply stands as a sort of blueprint of what we need to do to help bring about a new world. The question for us as a contemporary liberal religious community that knows the old ways and old God of monotheism no longer works, is what is the thing or things we might bring in from the margins of our culture and make central so as to gather up our world differently and more healthily? What might be for us the jar? What might be for us the 'god' that takes dominion everywhere and which can properly replace our old bankrupt concepts of God?

APPENDIX

Additional things noted by people in the period of conversation which immediately follows the address and the musical offering:

1. The need to ensure that with any ordering there remains some space for mystery.

2. Tennessee is mountainous so putting the jar on a *hill* is to put something odd in an odd place that most Tennesseans would not even notice as some kind of upland.

3. It was humorously noted that the Dominion jar (at least the one in the picture on the order of service) was made in Canada - what might it mean to place a Canadian jar on a US hill!.

4. It is like any landscape painting - when you notice a person in a landscape that pulls the picture together.

5. A couple of people just hated the poem and, in so far as they felt they understood it, thought it was wrong-headed.

6. I had the lid on but one person thought that this made it too closed. I had in mind something Heidegger said in his Der Spiegel interview about needing a god to save us. Such a god - it seems to me - needed to be imperturbable like Epicurus' understanding of the gods (that's why I had the lid on) but, at the same time, had to be able to be seen through, transparent (again, like Epicurus' gods - who could not in a physical way causally effect the world), so that our view of the natural world could clearly be seen for what it is (that's why I took it to be a glass jar).

7. Lastly one person reminded us that the famous Scopes trial took place in Tennessee in 1925 when a high school biology teacher, John Scopes, was accused of violating the state's Butler Act that made it unlawful to teach evolution. This trial took place, of course, two years after the publication of Harmonium, the collection in which 'Anecdote of a Jar' was published. However, this unexpected resonance with a famous event concerned with the theory of evolution and its often unwelcome reception in religious circles, seemed an appropriate place to pause.

So, lots of thoughts that just carried on being expressed for another hour over coffee.

Comments

To me your suggestion seems highly unlikely - but I don't pretend to be an expert on Stevens just someone who loves his poetry and spends a little time with it. Thanks for dropping by the blog and asking the question.

Warmest wishes,

Andrew

I wonder if Stevens was aware of the parable when writing his "anecdote".

The parable of the empty jar found in the Gospel of Thomas is a fascinating one but I can assuredly say that Stevens did not have it in mind when he wrote his poem. The reason for my confidence is that his poem was first published in 1919 but the first English translation the Gospel of Thomas is not published until 1959, fourteen years after it had been discovered in Egypt. It is true, of course, that three fragments of the gospel were discovered before 1919 but it was only after the 1945 discovery that it became apparent they belonged to the gospel. Secondly, the parable of the empty jar was not one of those three fragments. Given this we can assuredly rule out your suggestion. Stevens died in 1955 so it unlikely, though not impossible, that he remained wholly unaware of the gospel (or the parable) to the very end of his life.

However, it's worth saying that it seems to me to be a perfectly legitimate endeavour to read texts against/with each other to generate new, contemporary ideas and insights -- as long as, of course, that one doesn't do this reading in order to obscure an historical truth, namely that Stevens did not know the parable when he wrote his poem. Slavoj Žižek, calls this ‘short-circuiting’:

‘ . . . one of the most effective critical procedures [is] to cross wires that do not usually touch: to take a major classic (text, author, notion) and read it in a short circuiting way, through the lens of a “minor” author, text or conceptual apparatus (“minor” should be understood here in Deluze’s sense: not of “lesser quality”, but marginalized, disavowed by the hegemonic ideology, or dealing with a “lower”, less dignified topic). If the “minor” reference is well chosen, such a procedure can lead to insights which completely shatter and undermine our common perceptions’ (‘The Monstrosity of Christ’, Slavoj Žižek and John Millbank, MIT, 2009, pp. vii-viii).

Thanks for writing. Much appreciated.

Best wishes,

Andrew