“It is one thing to dance as though nothing has happened; it is another to acknowledge that something singularly awful has happened . . . and then decide to dance.”

|

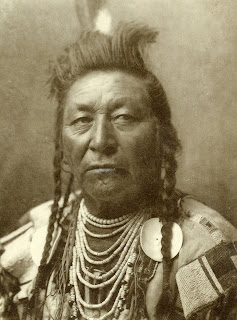

| Chief Plenty Coups |

On Friday I found that, as a liberal religious person, and although not myself a Liberal Democrat, I took very seriously Nick Clegg’s feeling expressed in his resignation speech that, “Fear and grievance have won, liberalism has lost.” Miliband could have added that so, too, had socialism lost.

But whether or not you agree with these conclusions, following the election questions inevitably arise for many of people, about who they are, and how they are to go on?

This general, very human, matter struck me as something that can meaningfully, usefully, and non-party politically, be talked about within our own community on this Sunday following the election.

It sent me back to a very beautiful and poignant book I introduced you to in 2011, “Radical Hope — Ethics in the Face of Cultural Devastation” by Jonathan Lear (Harvard University Press, 2008) which “raises a profound ethical question that transcends . . . time and challenges us all: [namely] how should one face the possibility that one’s culture might collapse?” As Lear says, “This is a vulnerability that affects us all — insofar as we are all inhabitants of a civilization, and civilizations are themselves vulnerable to historical forces.” This allows Lear to ask us a couple of important questions, “How should we live with this vulnerability? Can we make any sense of facing up to such a challenge courageously?”

But before turning to Lear’s case study it is important to recall that our own religious tradition was born out of a major collapse and trauma. Jesus was, as you all know, a faithful if radical Jew and, at the heart of Jewish life in Jesus’ time was the Temple in Jerusalem where he famously overturned the money changers tables because they were misusing this holiest of places. Without the Temple many people believed that there could be no (proper) Jewish people nor religion.

The first Temple, known as Solomon’s Temple (for which there has been found no archeological evidence by the way), was believed to have been destroyed in 586 BCE by Nebuchadnezzar II, when the Jewish leadership of the Kingdom of Judah were forced into exile in what is known as the Babylonian captivity.

Under Cyrus the Great of Persia (c. 600 or 576–530 BCE) it became possible both to re-establish the city of Jerusalem and to rebuild of the Temple, a task completed in c. 516 BCE, traditionally under Ezra-Nehemiah and so one traumatic destruction of the temple was survived.

But then, in 70 CE, under the Emperor Titus, the Romans decisively ended the four-year long Jewish Revolt by destroying the Temple a second time. The Temple was never rebuilt and the structure and shape of Judaism was radically and irrevocably changed. This traumatic event helped give prominence both to the local synagogue and the teachers of the Torah, the Rabbis. It also necessarily contributed to the development of the distinctive, domestic character of Judaism as we know it today, with it’s many home rituals.

But then, in 70 CE, under the Emperor Titus, the Romans decisively ended the four-year long Jewish Revolt by destroying the Temple a second time. The Temple was never rebuilt and the structure and shape of Judaism was radically and irrevocably changed. This traumatic event helped give prominence both to the local synagogue and the teachers of the Torah, the Rabbis. It also necessarily contributed to the development of the distinctive, domestic character of Judaism as we know it today, with it’s many home rituals.It is also important to understand that it was in this new Jewish context that Jesus’ own teaching and example came to flourish and, in the hands of the disciples and their followers, it eventually developed into the religion we know as Christianity. It was not simply the trauma of Jesus’ execution that drove the development of Christianity, it was also the trauma of losing the Second Temple and the collapse of the culture that centred upon it.

Only an acceptance of this allowed our forebears meaningfully to imagine that Jesus had promised to the Samaritan woman that it was possible to worship God no longer in the Temple (or, for the woman, on Mount Gerizim) but in spirit and in truth anywhere and everywhere (John 4:20-24).

|

| Crow Indians c. 1878-1883 |

Consequently, when the white European settlers came and not only destroyed the buffalo herds but also outlawed intertribal conflict, what it was to be a Crow was immediately placed in danger. Their remarkable chief, Plenty Coups (1848–1932), said of this period, “when the buffalo went away the hearts of my people fell to the ground, and they could not lift them up again. After this nothing happened.”

But what does this mean? To answer this let’s begin by concentrating on hunting buffalo.

Lear notes there is something here we are liable to miss if we are not careful because, when we say “It is no longer possible to hunt buffalo”, we are speaking of two things (Jonathan Lear “Radical Hope”, Harvard University Press, 2006, p. 38ff).

The first is that “Circumstances are such that there is no practical possibility of our hunting for buffalo” — i.e. there are simply no longer any buffalo to hunt.

The second is that we mean “The very act of hunting buffalo itself has ceased to make sense.”

Not clear about the difference? Well, Lear gives us a modern illustration to help:

Consider a person who goes into her favourite restaurant and says to the waiter, “I’ll have my regular, a buffalo burger medium rare.” The waiter [replies], “I’m sorry madam, it is no longer possible to order buffalo; last week you ate the last one. There are no more buffalo. I’m afraid a buffalo burger is out of the question.” Now consider a situation in which the social institution of restaurants goes out of existence. For a while there was the historical institution of restaurants — people went to special places and paid to have meals served to them — but for a variety of reasons people stopped organising themselves in this way. Now there is a new meaning to “it is no longer possible to order buffalo”; no act could any longer count as ordering. In general [Lear continues] these two sense of impossibility are not clearly distinguished because they often go together. (Jonathan Lear “Radical Hope”, Harvard University Press, 2006, pp. 38-39).

If only the first possibility had played out it would have been bad enough but, for the Crow, both occurred.

Now let’s turn to war and to an act which was for the Crow closely bound up with it, namely, the Sun Dance. This dance was a prayer-filled ritual asking for God’s help in winning military victory. But, as Lear points out, what is one to do with the Sun Dance when it has become impossible to fight — impossible in both the senses I’ve just noted. In essence a culture facing this kind of cultural devastation has three choices:

1. Keep dancing even though the point of the dance has been lost. The ritual continues, though no one can any longer say what the dance is *for*.

2. Invent a new aim for the dance. The dance continues, but now its purpose is, for example, to facilitate good negotiations with whites, usher good weather for farming, or restore health to a sick relative.

3. Give up the dance. This is an implicit recognition that there is no longer any point in dancing the Sun Dance. It is also to give up, of course, any hope of continuing as a Crow people.

By 1875 the Crow finally chose the third option. When, ten years later and by now on the reservation, Plenty Coups said “After this, nothing happened” Lear points out it is tempting to think that Plenty Coups simply meant no traditionally important events like the Sun Dance happened any more.

But, as Lear observes, it is

“also possible to hear him bearing witness to a deeper and darker claim: namely, that no one dances the Sun Dance any more because it is no longer possible to do so. . . . One might still teach people the relevant steps; people might learn how to go through the motions; and they can even call it the ‘Sun Dance’; but the Sun Dance itself has gone out of existence” (Jonathan Lear “Radical Hope”, Harvard University Press, 2006, pp. 36-37).

Remember that the two central shaping activities (hunting buffalo and the warrior life) that gave everything to the Crow had just gone out of existence. Imagine, just imagine, how that felt to the members of the tribe now herded together on their reservation. It is no wonder there were such high levels of depression and despair amongst Native American peoples.

But now I can turn to the theme of radical hope.

The Crow decided that they did want to survive in some fashion — it was a deep, existential decision — and to do this they first had to acknowledge that the old ways of living life had gone. For Plenty Coups that involved “the stark recognition that the traditional ways of structuring significance and meaning had been devastated.” But, in his beautiful book, Lear believes that for the Crow this recognition was not an expression of despair but the only way to avoid it. He points out that one must recognise the destruction that has occurred if one is to move beyond it. (Today, I particularly want to stress this point).

Having acknowledged this Plenty Coups and other members of his tribe returned to their old stories and dreams (dreams and their interpretation were, as I’m sure you know, key in tribal life) and they found ways radically to re-interpret them to find a traditional way Crow forward. There are some beautiful and moving examples of this in Lear’s book but I’ll just use that of the Sun Dance as it is here that I find a convergence with what I’m trying to say today.

In 1941, sixty-six years after they abandoned the Sun Dance, the Crow decided they wanted to re-introduce it but, at that point, they found that the steps of their version no longer existed in the memory of single member of the tribe. However, they pressed on by seeking out the leaders of the Sun Dance among the Shoshone tribe in Wyoming and, in so doing, learned the steps that their traditional enemies had danced when they hoped to defeat the Crow in battle — this is, of course, an important moment of reconciliation. But, you might ask, was this, is this, the maintenance of a sacred tradition or is it, to quote Lear “a nostalgic evasion — a step or two away from a Disneyland imitation of ‘the Indian’?.”

Lear thinks everything hinges on Plenty Coups' declaration that after the buffalo had gone and the warring had stopped “nothing happened” because it lays down something key if a genuinely vibrant tradition is to be maintained or reintroduced. As Lear says:

“It is one thing to dance as though nothing has happened; it is another to acknowledge that something singularly awful has happened . . . and then decide to dance” (Jonathan Lear “Radical Hope”, Harvard University Press, 2006, p. 153).

Because this acknowledgement was made the Crow's decision to dance again helped them, not only survive in some real and meaningful traditional way, but also eventually successfully to bring some of their unique traditional insights to the common table of modern American culture.

Plenty Coups is now a national hero and stands as a powerful example of reconciliation. The singularly awful happening the Crow experienced has not gone away but they have redeemed it — not only for themselves but, potentially, for the whole of modern USA as their stories have commingled and the resulted in an enrichment of the whole. Not everything Crow was salvageable but something was. They have been able to go on and to find ways to bring something meaningful of their old values and vision into the present.

None of this is to diminish or deny the horror they experienced as their culture collapsed around them. That will, forever, remain. But they did find an extraordinarily courageous way to keep continuity with the Crow faith through it all and it is a story we would do well to honour and learn from.

And, lastly, as I wrote this piece I was reminded of some words spoken in 1946 by the Unitarian minister, A. Powell Davies (1902-1957) to whom I introduced you a couple of weeks ago:

“Faith begins after you have faced the worst; faith is born from reality. Anything which comes in any other way is not faith and in the day of trial it lets us down. [If] We endure the pain just as though we did not have it [then we] are shrunken by pain into littleness or bitterness. But when reality is faced, the pain is endurable and the soul grows greater” (The Mind and Faith of A. Powell Davies, ed. William O. Douglas, Doubleday & Co., 1959, p. 273).

Comments

Details of the conference are here: http://www.climatepsychologyalliance.org/radical-hope-cultural-tragedy-conference-18th-april-2015-3/

Thanks for that bit of information. Most interesting. I see all the places are booked so that bodes well for the conference. I hope it goes well and I'd be interested to hear something of what transpires during it.

Best wishes and thanks again for dropping by the blog.

Andrew