The Sinai Schema—some theological thoughts on the Prime Minister's Christmas message—Holy Innocents' Day

|

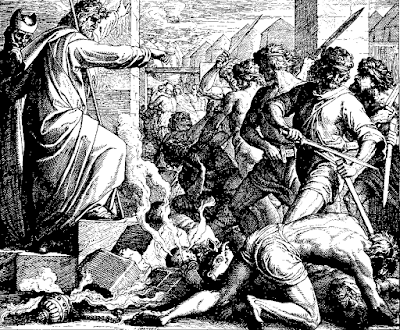

| Massacre of the Innocents by Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld (1794–1872) |

It is worth remembering that these stories are not historical accounts, rather they are etiological tales, i.e. tales designed to "explain" the origins of various religious practices, norms, natural phenomena, names of places and peoples etc. and that, therefore, as Peter Sloterdijk observes, "The true location of these events is purely in the stories themselves" ("In the Shadow of Mount Sinai", Polity Press, p. 27).

Given that the wider context of my words includes the horrific conflict going on in Syria it is not inappropriate to observe that, although Holy Innocents' Day is observed in the UK tomorrow, the 28th December, in the Western Syrian Christian tradition, it observed today.

From the publisher’s introduction to Peter Soloterdijk’s essay, “In The Shadow of Mount Sinai” (Polity Press, 2015):

“At the core of monotheism is the logic of belonging to a community of confession, of being a true believer — this is what Sloterdijk calls the Sinai Schema. To be a member of a people means that you submit to the beliefs of the community just as you submit to its language. Monotheism is predicated on the logic of one God who demands your utmost loyalty. Hence at the core of monotheism is also the fear of apotheosis, of heresy, of heterodoxy. So monotheism is associated first and foremost with a certain kind of internal violence, namely, a violence against those who violate their membership through a break in loyalty and trust.”

From the British Prime Minister, David Cameron’s Christmas 2015 message:

“It is because [our armed forces] face danger that we have peace. And that is what we mark today as we celebrate the birth of God’s only son, Jesus Christ – the Prince of Peace. As a Christian country, we must remember what his birth represents: peace, mercy, goodwill and, above all, hope. I believe that we should also reflect on the fact that it is because of these important religious roots and Christian values that Britain has been such a successful home to people of all faiths and none.”

—o0o—

Address

One of the many joys and privileges of training for ministry at Oxford was having the opportunity to meet and get to know, just a little, an historian whose 1952 book, “Hitler: A Study in Tyranny” was profoundly influential upon my own early thinking about history, Alan Bullock (1914-2004). He was also a lifelong Unitarian, his father had been a Unitarian minister, and he generously gave me some of his time in conversation about life, the universe and everything. On one occasion after Sunday chapel in Harris Manchester College I asked him what was the single most important thing he felt he had learnt from his study of figures like Hitler and Stalin? Without hesitation he replied that whenever you saw or heard expressions of the kind of ideology that might lead down similar, extremely dark paths, you were to challenge it, even if you only overheard it casually mentioned in the queue at a Post Office. I vowed that day to follow his advice.

But, as my own thinking has become more experienced, developed and nuanced (which is not the same as it being right, of course!) I have come to see how hard these kinds of dark paths are to identify in their earliest stages. Calling out something early on risks you being accused at best of foolishness and, at worst, of being necessarily alarmist and unreasonable. But this week, in David Cameron’s Christmas message, I heard some words that I think need to be called out as being something that, if followed through on, lies at the start of a very dark path indeed. I am deeply disturbed by them.

Here’s the relevant paragraph again:

“It is because [our armed forces] face danger that we have peace. And that is what we mark today as we celebrate the birth of God’s only son, Jesus Christ – the Prince of Peace. As a Christian country, we must remember what his birth represents: peace, mercy, goodwill and, above all, hope. I believe that we should also reflect on the fact that it is because of these important religious roots and Christian values that Britain has been such a successful home to people of all faiths and none.”

Firstly I point to his use of the highly-charged theological phrase, “God’s only son, Jesus Christ – the Prince of Peace.” Secondly, I point to this phrase’s use in the explicit context of a deepening and increasingly out of control armed conflict with certain groups holding to a particularly extreme, literalist, interpretation of another monotheistic tradition, namely, Islam.

Although I have my suspicions, I need to be clear that I don’t really have a clue about whether or not Cameron actually believes his own statement in any literal, theological way, but I do know that he’s playing with fire here because, as a politician, these words take him directly into the violence that lies at the heart of monotheism—a violence born out of the belief that "because our god is like no other, our people is like no other" (Sloterdijk, p. 21).

Let me briefly but, I hope, carefully take apart this power-keg I think Cameron is playing with.

Central to monotheism is a belief in a single, only God. As the Hebrew Scriptures put it in the first of the ten commandments found in Exodus 20:1–17, and then at Deuteronomy 5:4–21: “Thou shalt have no other gods before me”; as Jesus puts it in John 17:3 “And this is life eternal, that they might know thee the only true God, and Jesus Christ, whom thou hast sent”; as the 112th sura of the Qur’an, “Sūrat al-Tawhīd”, puts it, “Say: He is Allah, the One and Only; Allah, the Eternal, Absolute; He begetteth not, nor is He begotten; And there is none like unto Him.”

It is believed by each of these groups that with this single God they have made some kind of covenant and that this same God has divinely revealed to them certain authoritative eternal laws, texts, practices and people. The primary model for this monotheistic covenantal relationship is, of course, the one found in the Hebrew texts and a primary story within this model is the story of the Golden Calf that we heard earlier in our readings.

Now let’s note an important dynamic at play in this story. Even though the Hebrew writers have Moses first change God’s mind about wanting to destroy all his people and start over, on going down the mountain and seeing the calf and all his people dancing before it, Moses himself has a change of mind — he finds himself agreeing with God’s original decision. In a single moment he decides that continued loyalty to his people’s single God in fact trumps and breaks all the laws of that same God just given to him — including, as we shall soon horrifically see, the law not to kill. He throws down the tablets of stone upon which God has written them, takes the Golden Calf, this strange and foreign god, burns it with fire, grinds it to powder, scatters it on the water, and makes all his people drink the awful cocktail. Then, when this does not stop the people he calls out, “Who is on the Lord’s side? Come to me!”

Only the sons of Levi choose to gather around him and to them he says those awful, genocidal words:

Thus says the Lord, the God of Israel, “Put your sword on your side, each of you! Go back and forth from gate to gate throughout the camp, and each of you kill your brother, your friend, and your neighbour.”

The story tells us about three thousand of the people fell on that day and that these actions served the Lord and brought a blessing upon themselves.

The German philosopher and cultural theorist Peter Soloterdijk (b. 1947) has written about this story in an essay published just this month called “In The Shadow of Mount Sinai”:

“The covenant has the form of a non-mixing contract and a non-translation oath [i.e. a promise is made never to try and see your God in another form, say a golden calf or, another people], [and these are] combined with the highest salvific guarantees. Whoever mixes themselves is eliminated, and whoever translates falls from grace” (Sloterdijk, p. 23).

And here’s a summary of Sloterdijk’s overall view found in his essay:

“At the core of monotheism is the logic of belonging to a community of confession, of being a true believer — this is what Sloterdijk calls the Sinai Schema. To be a member of a people means that you submit to the beliefs of the community just as you submit to its language. Monotheism is predicated on the logic of one God who demands your utmost loyalty. Hence at the core of monotheism is also the fear of apotheosis, of heresy, of heterodoxy. So monotheism is associated first and foremost with a certain kind of internal violence, namely, a violence against those who violate their membership through a break in loyalty and trust.”

(The story of the massacre of the innocents echoes this schema in that Herod is presented as being frightened of losing the loyalty of his own subjects to this child Jesus, a divine representative of a different god to the one to whom Herod is, we may presume, loyal).

At this point it’s worth reminding you of something said by the insightful, if deeply problematic, German jurist and political theorist Carl Schmitt (1888–1985) in his 1922 essay “Political Theology”, namely, that:

“All significant concepts of the modern theory of the state are secularized theological concepts . . . in which they were transferred from theology to the theory of the state, whereby, for example, the omnipotent Cod became the omnipotent lawgiver” ("Political Theology," MIT Press, 1985, p. 36)

The problem is, as I see it anyway, that the religious violence of the Sinai Schema is still encoded in our secularized national political life. Indeed, because of this, Sloterdijk feels it is better to point not so much to monotheism as the problem but to something more general which is any kind of "covenantal singularization project". I think we may say that it is more helpful to think of monotheism as a subset of this latter project.

Anyway, over the last century this schema/project has been reasonably well sublimated by us within liberal democratic states, i.e. the socially unacceptable impulse to do violence to those outside your own, immediate, particular national or religious group has been transformed (often unconsciously) into a more open-hearted, understanding and tolerant way of dealing with difference.

But this shadow of the Sinai Schema means that, under certain circumstances, our politics and poorly educated politicians (at least in terms of religion and theology) are highly susceptible to becoming re-theologised and a group like ISIS seem to have realised this. They are, I think, intuitively alert to the violence that is implicit within the monotheistic, Sinai schema and they seem to be increasingly successfully in being able to lure some of our politicians into fighting them by reviving in our own countries some kind of Christian monotheism as an antidote to, in this case, “Islam”—to encourage a revival of the idea that "because our god is like no other, our people will be like no other."

I think that this has, in truth, been going on covertly for a while now (at least since the attacks in September 11, 2001 and Tony Blair's Prime Ministership) but Cameron’s explicit claim in this message that this is a Christian country (i.e. not a secular and multi-faith one) and that, at Christmas, we are centred on “God’s only son, Jesus Christ” and that this only son is, “the Prince of Peace”, i.e. not a prince of violence as (presumably) our current enemy's major religious figures are, just reeks to me of a revival of the Sinai Schema.

(As a member of the congregation perspicaciously noted, the way Cameron presents his Christmas message can easily make it look as if he thinks the British Armed Forces are acting under "the banner of Christ".)

(As a member of the congregation perspicaciously noted, the way Cameron presents his Christmas message can easily make it look as if he thinks the British Armed Forces are acting under "the banner of Christ".)

The problem is that the One God ISIS and Cameron are messing with is the kind of genie who, once out of the bottle and back in the world of politics, is not at all easy to get back in again; a fact that was noted at a conference I chaired a few years ago with both great sadness and anger by a senior NATO General who had served in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Now, I don’t know whether we can do much about this right at the moment but I am asking you to keep an eye on this tendency during the coming year and, in the spirit of Alan Bullock, to have the courage to call it out as a very dangerous thing.

The very least we can do in a liberal free-religious setting (such as the one in which this address is being given) is to draw people’s attention to this matter and, although we may not be able to put out the fire ourselves, we can usefully shout loudly “Fire!” and have at least half a chance of getting a group of effective firefighters on the scene in time to save the building that is any genuinely tolerant, secular, democratic state.

Comments