Theatre or Spectacle? A critical question about the forthcoming Royal Wedding

READINGS: 1 Timothy 2:1-4 (trans. David Bentley Hart)

READINGS: 1 Timothy 2:1-4 (trans. David Bentley Hart)First of all, therefore, I encourage petitions, prayers, intercessions, thanksgivings to be made on behalf of all human beings, on behalf of kings and of all who hold preeminence, so that we might lead a tranquil and quiet life in all piety and solemnity. This is a good and acceptable thing before our saviour God, who intends all human beings to be saved and to come to a full knowledge of truth.

From Faith of the Faithless: Experiments in Political Theology by Simon Critchley (Verso Press, 2012 pp. 51-53)

In [Rousseau’s Letter to D’Alembert of 1758] he restates Plato’s critique of the tragic poets in the Republic where theatre is excluded from the well-ordered polis because it is the mimesis or imitation of a mere appearance, rather than an attention to the true form of things which should be the proper concern of the philosopher.

This critique of theatre . . . runs together with Rousseau’s proposal to replace theatre with civic spectacle. What is essential to such spectacles is precisely that they are not representations but the presence to itself of the people coming together outdoors in daylight and not dallying in the darkness of the theatre, whose very architecture, says Rousseau, is reminiscent of Plato’s cave:

“Plant a stake crowned with flowers in the middle of a square, gather the people together there, and you will have a festival. Do better yet, let the spectators become an entertainment to themselves, make them actors themselves, do it so that each see and loves himself in the others so that all will be better united.”

In the civic spectacle, the people do not passively watch a theatrical object of representation, but rather become the actors and enactors of their own sovereignty Rousseau’s defense of popular sovereignty in The Social Contract is of a piece with his critique of any and all forms of representative government. The only way of attaining political legitimacy is to root sovereignty in the will of the people not in some external, representative authority. The people should be the actors in the theatre of their state. In this context, festival becomes the lived manifestation of popular sovereignty, the reinforcement of the people’s individual and collective autonomy that allows for the identification between law and patriotism, where the latter is the glue connecting the people to the former.

The civic festival is the enacting of the general will without the mediation of representation.

—o0o—

ADDRESS

Theatre or Spectacle? A critical question about the forthcoming Royal Wedding

As I begin this address it seems worth reminding you of my address on April 15 entitled, “Some irregular thoughts on Anarcho-Monarchism” in which I hope I made it clear why the question of how one is governed is clearly not simply a secular, technical question but always in some fashion a principled theological and, therefore, religious one and that this is why questions related to those who govern us are wholly appropriate things to consider in a church setting.

Christianity’s relationship with state or civic power in general has always been complex and problematic. On the one hand there have been many periods when those who were in power have threatened the freedom of religious communities and, on the other, when religious communities have themselves become directly linked to power they have often, in their turn, threatened the freedom of others. But, whatever you think about the overall rightness or wrongness of mixing religion with state and civic power, our reading from 1 Timothy (2:1-4) which we heard earlier expresses what has become in our own age the default position of most churches.

But this compromise — and compromise is not necessarily a dirty word — with those who are currently in power should, at the same time, never ever be used to stop us from turning a critical eye upon such matters and today, following the example of the great essayist Michel de Montaigne (Essay 56 On Prayer) I want to do this by “seeking the truth not laying it down.”

It is in this spirit of enquiry that today that, again following Montaigne, the “notions which I am propounding have no form and reach no conclusion” because I want simply to leave you with an important question concerning the difference between theatre and spectacle and whether the Royal Wedding celebrations next weekend are the former, or the latter. What you then do with your answer to this question I leave entirely for you to decide.

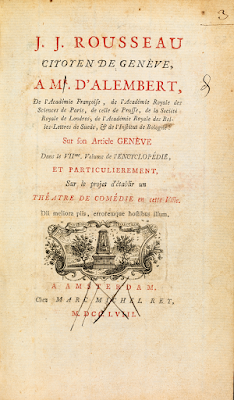

The most influential attempt within our own Western European culture to differentiate between theatre and spectacle was made by Rousseau who, following Plato, was very suspicious of theatre. Simon Critchley reminds us that:

In [his “Letter to D’Alembert” Rousseau] restates Plato’s critique of the tragic poets in the “Republic” where theatre is excluded from the well-ordered polis because it is the mimesis or imitation of mere appearance, rather than attention to the true form of things which should be the proper concern of the philosopher (Faith of the Faithless, Verso Press, 2012, p. 51).

Given this Rousseau proposed that theatre should be replaced with civic spectacle because what is essential to such spectacles is precisely that they are “not representations but the presence to itself of the people coming together outdoors in daylight and not dallying in the darkness of the theatre, whose very architecture, says Rousseau, is reminiscent of Plato's cave”:

“Plant a stake crowned with flowers in the middle of the square, gather the people together there, and you will have a festival. Do better yet; let spectators become an entertainment to themselves; make them actors to themselves; do it so that each sees and loves himself in the others so that all will be better united” (ibid p. 52).

Simon Critchley sums up Rousseau’s basic point by noting that

“In the civic spectacle, the people do not passively watch a theatrical object of representation, but rather become the actors and enactors of their own sovereignty” (ibid p.52).

Now, in order to help get us back to my question about whether the Royal Wedding celebrations next weekend are theatre or spectacle we need to ask two supplementary ones.

The first is whether or not watching the Royal Wedding next Saturday is an example of “we the people” becoming an entertainment to ourselves in which we are the actors and enactors of our own sovereignty? In short, is the Royal Family genuinely representative of you and me and, therefore, of our sovereignty as a people?

The second is, if we take part in any other kind of celebratory public event next weekend where the Royal Family are not themselves present, are we witnessing an example of “we the people” becoming an entertainment to ourselves in which we are the actors and enactors of our own sovereignty as a people?

So are the events connected with next weekend’s Royal marriage going to be theatre or spectacle?

The only answer that could possibly satisfy us as a people (rather than as individuals) depends, of course, on whether there actually exists today something we can meaningfully call a people who might genuinely be able to experience and celebrate a shared understanding of in what consists its collective sovereignty.

I don’t think I’m saying anything particularly controversial when I note that I find it harder and harder to see what for us this genuinely collective understanding and experience of sovereignty might be. I’m haunted in this matter by a memory from my time teaching music in a Young Offenders Institution (a closed prison for under 18s) at Hollesley Bay in Suffolk during the early 90s. I was teaching guitar to a young lad who was inside for violent, armed robbery and he was struggling to recognise, let alone play, even the most simple musical example. Perhaps, I thought, he was a rare example of someone who was genuinely tone deaf. So to check I played him “Happy Birthday”. No, he told me, he didn’t know it. Now you might think that this was strong evidence in favour of my conjecture but I thought I’d try another example first and chose the British National Anthem, “God Save The Queen”. To my surprise he immediately said “Yes! I know that“ and instantly added “It’s the theme tune for the boxing.” It showed me two very disturbing things simultaneously. The first was that here was a eighteen year-old lad to whom no one had even played “Happy Birthday” and, the second, that what I had assumed would be a tune connected to a shared understanding of our sovereignty simply didn’t exist. I see no evidence that this situation has improved at all in the intervening thirty odd years.

In my own adult life my only personal experience of what seemed to me to be a genuine civic spectacle has not been had here but in France where, over the years, I have spent a good deal of time both working as a musician and also staying with various French friends for fairly extended periods.

|

| Villagers in Bédarrides (photo source) |

What struck me as I sat on a straw bale in the village square surrounded by hundreds of happy people was that this was genuinely a civic spectacle, one which was speaking about the people’s sovereignty. Firstly, even though evening was falling, we were coming together outdoors in daylight and we were not dallying in the darkness of the theatre; this lively village square was most certainly not Plato’s cave. Secondly, most people in the village were involved in the spectacle in some way or another having either made the costumes, built the sets, provided the horses and the lights, written the script or, of course, by playing the parts. They also all took time to eat and drink together before hand and continued to celebrate together long into the night after the re-enactment had finished. And, thirdly, it was clear I was witnessing a people who were (for this evening at least) an entertainment to themselves, who had become actors and enactors themselves and by so doing it was possible for them each see and love themselves in the other so that they would all be better united. This unity was no better expressed than in the collective proclamation of “liberté, égalité, fraternité” which is, of course, a succinct expression of in what consists their sovereignty as a people.

Now I am not making here a claim for the perfection or even general desirability of any or all of the five French Republics — or indeed this individual spectacle — rather I’m simply trying to point you towards in what would consist a genuine “we the people” and a genuine civic spectacle.

Of course, the history of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is very different from the French Republic and so one cannot make a simple, direct translation from one to the other. However, this illustration from France can help us ask where, if anywhere, in our own nation’s celebrations this weekend might we truly see in ourselves the actual presence of us as a people who are speaking of our sovereignty?

It matters because I’d like to believe in the possibility that as a people — and not merely as individuals — we would want each of us to see and love ourselves in others so that we can all be better united as a people. I’d genuinely like to believe that somewhere this weekend there will be a meeting of a people that is not merely the ultimately empty entertainment of which Juvenal once spoke (Satire 10.77–81), namely, bread and circuses — of the wealthy and powerful simply offering us “events” that distract us from the real, pressing questions of our age.

Now, one of the great joys and privileges of being part of a small, independent, religious community like this one is that, at our best, when we meet we are present to each other in a way that can help us see and love ourselves in others and so become better united as a community. We do this because, holding to the claim we inherit from Jesus that to love God is to love neighbour as ourselves, our self-understanding of our sovereignty as a liberal religious community is expressed by showing to each other (and those whom we meet) what this means in practice. Indeed, one of the chief reasons I continue to encourage more of you to become involved in both the active life of this community is because only this kind of real engagement with each other will ensure we here are engaged in religious spectacle and not merely creating religious theatre in which we play only with appearances.

But, alas, alack, our local community’s weekly religious spectacle, is clearly not representative of the state of affairs that generally obtains today more widely in our national civic life.

Given this, this coming weekend, wherever you are and whatever you are doing at 12 noon (the time of the wedding) I simply request all of you at that moment to ask about what is going on around you; is what you are seeing and example of people being actors and enactors of our own actual sovereignty as a people or are you seeing people merely playing with appearances; are people engaging in spectacle or simply witnessing theatre?

Having thought about Rousseau’s question (affirmatively, negatively or, perhaps, by dismissing it as a false binary — which it almost certainly is) then you may find yourself in a better place to go on to ask yourself about the efficacy or otherwise of concepts concerning “a people”, a “nation”, “patriotism”, “sovereignty”, “mass entertainment” and many others. But these are all questions for another day . . .

Comments