Some philosophical lessons learnt from the contemplation of marvellous puddles—or one way to keep poetry and science together

|

| Grant Snider's excellent page can be found at this LINK |

From Lucretius’ De Rerum Natura [On the nature of things] (1st century BCE) trans. James I. Porter Lucretius and the Sublime in The Cambridge Companion to Lucretius, ed Stuart Gillespie and Philip Hardie, Cambridge University Press 2007, p. 173)

A puddle of water no deeper than a single finger-breadth, which lies between the stones on a paved street, offers us a view beneath the earth to a depth as vast as the high gaping mouth of heaven stretches above the earth, so that you seem to look down on the clouds and the heaven, and you discern bodies hidden in the sky beneath the earth, marvellously. (DRN Book 4:414-419)

From Epicurus’ Principal Doctrines (3rd century BCE) trans. Brad Inwood and L. P. Gerson

11. If our suspicions about heavenly phenomena and about death did not trouble us at all and were never anything to us, and, moreover, if not knowing the limits of pains and desires did not trouble us, then we would have no need of natural science.

12. It is impossible for someone ignorant about the nature of the universe but still suspicious about the subjects of the myths to dissolve his feelings of fear about the most important matters. So it is impossible to receive unmixed pleasures without knowing natural science.

13. It is useless to obtain security from men while the things above and below earth and, generally, the things in the unbounded remained as objects of superstition.

From Lucretius’ De Rerum Natura [On the nature of things] (1st century BCE) trans. Walter Englert

Therefore this fear and darkness of the mind must be

shattered

apart not by the rays of the sun and the clear shafts

of the day but by the external appearance (species) and inner

law (ratio) of nature (naturae species ratioque)

(DRN Book 1:146-148, 2:55-61, 3:91-93, 6:35-41)

Naturae species ratioque

This can be translated as above or, as I am coming to prefer, following Thomas Nail (in his extraordinary book (Lucretius 1: An Ontology of Motion, Edinburgh University Press, 2018, p. 67) “the material conditions for nature as it appears.”

Shadows in the Water by Thomas Traherne (1636/37–1674)

—o0o—

Some philosophical lessons learnt from the contemplation of marvellous puddles—or one way to keep poetry and science together

We are now firmly in the season of autumn and, with the coming of autumn, there comes the rain, and with the coming of the rain there come puddles.

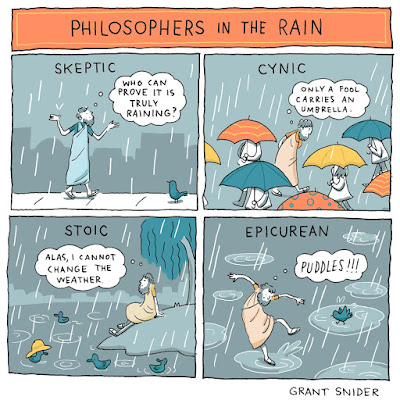

Spending a great deal of time in the Cambridge University Botanic Garden as I do, at this time of year I quite often see very small children in their new wellington boots discovering the simple delight of being able to splash about in a puddle. It’s an expression of joy that serves to make even the most skeptical, cynical, stoical of people break into an involuntary smile and, as the wonderful cartoon by Grant Snider suggests, as a good Epicurean I’ve managed to maintain my love of puddles for their pure puddliness.

But, aside from the simple joy that splashing about in them affords us, a puddle’s puddliness also offers an Epicurean a powerful reminder about what is for them a profound truth concerning the nature of things.

One of Lucretius’ central, practical pastoral concerns, (inherited from his philosophical hero Epicurus), was to free people from their superstitious fear of the gods. Lucretius could see that, in the end, belief in the reality of supernatural beings who demanded worship and who judged and metered out rewards and punishments upon humankind, in the end, always has less than optimal consequences. In his poem Lucretius offers the reader many striking examples of how people were continually being oppressed and made unhappy and fearful by such supernatural religion and, alas, how they also sometimes even lost their lives thanks to its obsession with power and control. As you heard earlier Lucretius thought this fear (along with, for example, those about death and the possibility of an afterlife) were “shattered apart not by the rays of the sun and the clear shafts of the day but by the external appearance (species) and inner law [or material conditions] (ratio) of nature” — naturae species ratioque (DRN Book 1:146-148, 2:55-61, 3:91-93, 6:35-41).

|

| Venus on seashell, from the Casa di Venus, Pompeii. Before AD 79 |

Lucretius was, as you may know, not only a fine and original philosopher but also a poet of genius praised by both Virgil and Cicero. As a poet, he understood well that being the kind of beings we are, we are always-already engaging with the natural world as much through our poetry and myths as through the kinds of activities which, in time, became called the natural sciences. He felt that, somehow, they were worth keeping in creative step with each other with each being allowed the space and opportunity appropriately to illuminate the other.

He understood that as we looked at the world and its multifarious phenomena such as the wind, rain, lightning, thunder, the movement of the heavenly bodies above us, the stars and sun and moon and so on, it had been a recurring natural human tendency to see in them the actions of divine, powerful beings. It was as a consequence of this tendency that the enduring myths and poems about the gods were born as too, alas, were our associated superstitious religions.

Holding this in mind we can now quietly turn back to begin to contemplate our puddle, or at least we can when all the excited, wellington boot-clad children have moved on and its surface has stilled once more.

In book four of the De Rerum Natura Lucretius invites us to contemplate this image because it helps him illustrate how the external appearance (species) and inner law or material conditions (ratio) of nature can be held together in a way that both allows us to continue to enjoy some of the poems and myths about the gods our forebears had read of the world’s surface, nature’s face or species but without, at the same time, being lured into believing that they are, somehow, actual beings.

To show you what he means, for full effect, let us now imagine ourselves in the Cambridge University Botanic Garden looking down into a largish puddle with the sun shining overhead in a white cloud-dappled blue sky and with a golden, leaf-bedecked branch over-hanging us whilst a few rooks circle high above that. As we look down into the water at the reflection below we can experience a real sense of awe and wonder at the vertiginous sight we behold as we seem to look down through a hole in the pavement into what can appears to be whole other world below.

It’s the kind of vertiginous view that has always had the power to create in our imaginations all kinds of poetic stories and images that, unless we are very careful, can easily lead us astray. I had Susanna read Thomas Traherne’s poem “Shadows in the Water” because to me — and no doubt to Lucretius were he with us today — it is a classic example of being led quite astray.

Traherne was a devout, seventeenth-century Anglican minister and theologian who was genuinely interested in the natural sciences. However, despite this interest, as his poem suggests, because science was always secondary to his strong, a priori commitment to the existence of a supernatural god he was only too willing to allow himself to read off from the world’s surface — nature’s face or species — a marvellous image which he could then beguilingly turn into what he thought was an index of an underlying (or overarching) supernatural reality, the very home of his “very God of very God.” In this poem, although it is true he brings this idea before us for contemplation in a gentle way — i.e. he doesn’t ram his belief down our throats in an obviously doctrinal or dogmatic fashion — we must not lose sight of his general desire as a clergyman to encourage us to believe in the reality of his supernatural, omniscient, omnipresent, omnipotent god and the existence of another, heavenly world that lies just beneath or behind the thin skin of our everyday world.

However, when looking down into his modest puddle Lucretius sees something very different, but to him, and to me, he sees something even more marvellous.

Now, remember Lucretius thought that the kind of fear and darkness of the mind to which Tranherne clearly fell prey would be shattered apart not by the rays of the sun and the clear shafts of the day but only by BOTH the external appearance (species) and inner law or material conditions (ratio) of nature — naturae species ratioque.

So let’s start with the inner law or material conditions of nature (the ratio). We’ll then turn to external appearance (species) and, finally, to why together they gift us something more marvellous and joyful than even someone like Traherne could have imagined.

Remember that in our readings you heard three of Epicurus’ principle doctrines. Well, Lucretius took them with the utmost seriousness because he saw that the natural sciences (φυσιολογίας — “inquiring into natural causes and phenomena”) were particularly well-suited to stop us from being led needlessly astray by the surface appearance of nature into believing in the existence of the gods and, therefore, of easily falling prey once again to the claims of supernatural religion with all its many fears and oppressions. The natural sciences he realised gave us a powerful insight into nature’s ratio, that is to say its inward laws, workings or material conditions, which, in turn, had the power simply to dissolve — or more dramatically, shatter — our fears about the existence of the gods and remove this and other darknesses from our minds.

Just to remind you, Lucretius thought that everything — without exception — was made, not by supernatural beings, but by the natural fluxes and flows of matter which endlessly went on to fold into atoms which then flowed together and combined to make all the things visible to us in our universe. The natural sciences of Lucretius' and our own day have showed us nature's ratio more clearly than even the rays of the sun ever could; we know that there are no such things as the gods imagined by supernatural religion and that, therefore, we also need never again be fearful of them nor bow to the demands of superstitious religion.

OK. But let’s not forget that Lucretius thinks this shattering is achieved by both the inner law (ratio) of nature and, AND, it’s external appearance (species) — naturae species ratioque.

At this point you need to recall that, as a poet, Lucretius understood well that being the kind of beings we are, we are always-already engaging with the natural world as much through our poetry and myths as through the kinds of activities which, in time, became called the natural sciences.

His own poem, the De Rerum Natura, shows us that, as a poet Lucretius didn’t want to lose all the wonderful poems and myths about the gods our forbears had constructed by reading them off nature’s face — of which the surface of the puddle is an exemplary example. These appearances were for him and us still perfectly capable of telling us all kinds of things (good and bad) about how humans are in the world, they can still entertain us, make us laugh and cry, become the subjects for songs and plays, provide us with inspiring and cautionary stories to help us explore all kinds of moral questions about how best to behave and so much more besides.

|

| Cybele |

“Endowed with this emblem [a crown — denoting her creative and sustaining power], the image of the divine mother is now carried with horrifying effect throughout the earth” (DRN 2:608-9 my emphasis).

In other words Lucretius is saying that when and wherever people have stopped understanding her poetically — as a marvellous appearance read off the surface or face of nature (species) — and have turned her into an actual goddess to whom sacrifice and praise must now be offered, stupid and horrific things inevitably followed. For Lucretius, although nature (in the poetic guise of Venus or Cyble) “is everything, the pure movement of matter; it makes no sense to sacrifice or pray to her” (Thomas Nail, Lucretius 1, p. 236), when people make her into actual goddess she is a disaster, a veritable horror.

The humble puddle is an aide-memoire which helps us resist taking this wrong turn for, whenever a good Epicurean sees someone beginning to take a surface, poetic appearance of nature as being real in the wrong kind of way, all they need to do is remind that same person of the puddle and show that all it takes to dispel the illusory image is to recall the ratio of nature, put one’s finger into the shallow water and wiggle it about. Even better, one might be able to find both a happy child and an Epicurean philosopher joyfully to jump about in the puddle to reveal the same thing.

What Lucretius ultimately wants to show us by using the puddle is that the reflection of the sky one sees in it is marvellous, truly marvellous—not as an index to another supernatural realm and its gods as it was for Traherne but as both “an appearance of nature and as an index to the wondrous truths of physics” (John I. Porter, Lucretius and the Sublime in The Cambridge Companion to Lucretius, ed Stuart Gillespie and Philip Hardie, Cambridge University Press 2007, p. 173).

—o0o—

For those interested in exploring a more general view of the philosophy of Epicurus and Lucretius in the modern context the following ten minute video by Luke Slattery is worth a watch.

Comments