Before we make new policies, we need new metaphors—What would it be to live a life that is more like the life of plants?

|

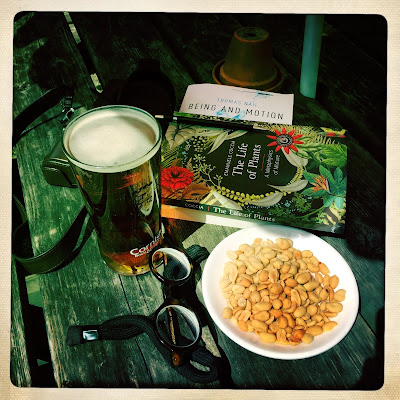

| Reading Coccia's book at the Green Man, Grantchester |

Once blasphemy against God was the greatest blasphemy, but God died, and thereupon these blasphemers died too. To blaspheme the Earth now is the most dreadful offence, and to esteem the bowels of the inscrutable more highly than the meaning of the Earth.

From “The Life of Plants: A Metaphysics of Mixture” by Emanuele Coccia (Polity Press, 2019, pp. 91-92)

We continue to conceive of ourselves through the prism of a falsely radical model, we continue to think the living being and its culture from a false image of roots (because they are isolated from the rest) — as if, by dint of conceiving of the root as reason, we have transformed reason itself and thought into a blind force of rooting, into the faculty of constructing a cosmic connection with the Earth.

[. . .]

Fidelity to the Earth — the extreme geotropism of our culture, its will, and its insistence on “radicalness” — has an enormous price: it means devoting oneself to the night, choosing to think without the Sun. Philosophy seems to have chosen, several centuries ago, the way of darkness.

Geocentrism is the delusion of false immanence: there is no autonomous Earth. The Earth is inseparable from the Sun. To go toward the earth, to dig into its breast means always to raise towards the Sun [think of plants at this point which do just this and which, in doing this, also make the air we breath]. This double tropism is the breath itself of our world and its primary dynamism. It is this same tropism that animates and structures the life of plants and the existence of stars: there is no Earth that is not intrinsically tied to the Sun, there is no Sun that is not in the course of making possible the superficial and profound animation of the Earth. To the lunar and nocturnal realism of modern and postmodern philosophy, one should oppose a new form of heliocentric, or rather an extremization of astrology. This is not, or not only to make the simple assertion that the stars influence us, that they govern our life, but to accept all this and to add that we also influence the stars, because the Earth itself is a celestial body among others, and everything that lives on it (as well as in it) is of an *astral* nature. There is nothing but sky, everywhere, and Earth is one of its portions, a state of partial aggregation.

—o0o—

ADDRESS

Before we make new policies, we need new metaphors—What would it be to live a life that is more like the life of plants?

During the last couple of weeks, I have had many more direct, continuous and conscious encounters with the life of plants than I usually do. It’s not that I don’t already spend a lot of time enjoying their company either on cycle rides or walks, or in the Cambridge University Botanic Garden but, this week, circumstances meant that I found myself helping Susanna to ready the church garden for yesterday’s splendid Christ’s Pieces Residents’ Association open gardens event. Additionally, the experience was for me intensified by my continued reading of the Italian philosopher Emanuele Coccia’s recent book “The Life of Plants: A Metaphysics of Mixture” to which I introduced you last week and in which he wrote that:

During the last couple of weeks, I have had many more direct, continuous and conscious encounters with the life of plants than I usually do. It’s not that I don’t already spend a lot of time enjoying their company either on cycle rides or walks, or in the Cambridge University Botanic Garden but, this week, circumstances meant that I found myself helping Susanna to ready the church garden for yesterday’s splendid Christ’s Pieces Residents’ Association open gardens event. Additionally, the experience was for me intensified by my continued reading of the Italian philosopher Emanuele Coccia’s recent book “The Life of Plants: A Metaphysics of Mixture” to which I introduced you last week and in which he wrote that:The origin of our world does not reside in an event that is infinitely distant from us in time and space, millions of light years away; nor does it reside in a space of which we no longer have a trace. It is here and now. The origin of the world is seasonal, rhythmic, deciduous like everything that exists. Being neither substance nor foundation, it is no more in the ground than in the sky, but rather halfway between the two. Our origin is not in us—in interiore homine—but outside, in open air. It is not something stable or ancestral, a star of immeasurable size, a god, a titan. It is not unique. The origin of our world is in leaves: fragile, vulnerable, yet capable of returning, of coming back to life once they have passed through the rough season.

You will also recall that in an interview about the book he reminded us:

Every time we breathe . . . we come into close or distant contact with plants. We feed on their detritus, on what they expel . . . which is oxygen. This banal event is the basis of all existence. Respiration is an act through which we immerse ourselves in the world and allow the world to immerse itself in us — the world of plants.

Given the confluence of some actual gardening and philosophising it’s not much of an exaggeration to say that every breath I took this week played a part in my ongoing reflections, not only on the words you heard in our readings last week but also on those you have heard this week. It’s also important to note that every breath I took was also accompanied by an acute awareness of how polluted is our city air and this, in turn, necessarily continually brought back into mind the climate emergency we are now facing.

Now, as most of you know, I’m a great admirer of Nietzsche’s work and so it was almost inevitable that at some point in all this I’d find myself recalling the words you heard earlier from “Thus Spake Zarathustra” (Prologue, section 3):

Once blasphemy against God was the greatest blasphemy, but God died, and thereupon these blasphemers died too. To blaspheme the Earth now is the most dreadful offence, and to esteem the bowels of the inscrutable more highly than the meaning of the Earth.

Now, I finished my first close reading of Cocchia’s book this week over a pleasant pint at the splendid Green Man pub in Grantchester following a lovely spring walk through the meadows (see picture at the head of this post and the black and white photos here and below) and, no sooner had I sat down to begin to read the final five chapters than I came across the self-same words of Nietzsche’s. As Coccia notes, “It would be difficult to find words that can summarise with greater precision the spirit of the new world religion that defines the contemporary world” (p. 89).

“Indeed,” I said to myself and nodded sagely. As I looked up from the book and took my first refreshing sip of local English ale, all whilst being bathed in the deliciously warm spring sunshine, I found myself already beginning to agree with what I thought Coccia was about to say in connection with these words. But only a few sentences on I realised Coccia was not going to say what I thought he was and was going to introduce me a new, challenging and very exciting idea, part of which is found in the extract from his book you heard earlier. You see Coccia feels there is a problem with Nietzsche’s words, especially as they have been taken up by our various contemporary environmentalist and ecological movements — and, I have to admit, as they have also been, for the most part, taken by me.

“Indeed,” I said to myself and nodded sagely. As I looked up from the book and took my first refreshing sip of local English ale, all whilst being bathed in the deliciously warm spring sunshine, I found myself already beginning to agree with what I thought Coccia was about to say in connection with these words. But only a few sentences on I realised Coccia was not going to say what I thought he was and was going to introduce me a new, challenging and very exciting idea, part of which is found in the extract from his book you heard earlier. You see Coccia feels there is a problem with Nietzsche’s words, especially as they have been taken up by our various contemporary environmentalist and ecological movements — and, I have to admit, as they have also been, for the most part, taken by me.This is because full involvement in what Coccia calls the geocentric “cult” of fidelity to the Earth all too easily can keep a person from seeing that there is “no autonomous Earth” because the earth is “inseparable from the Sun.” To recognise this is, of course, also to recognise that there is no absolute separation between the Earth and the Sun. The whole solar system (and in fact the whole of reality) is a mixture, it can be thought of as being itself an extended, fluid atmosphere in which everything depends on everything else. To make the earth sovereign, independent and, somehow, of greater value and worth than any other aspect of the mixture is to make a big mistake about reality.

True enough, given that this hospitable earth is our home and its well-being should, therefore, occupy much of our thoughts, passions and actions but, even so, at the same time we must not forget that it’s very hospitability is always already dependent on being part of a mixture that includes the inhospitability of the sun as a raging star (after all we can’t live on — or too near — the sun) and the inhospitability of the space that exists between it and us (we can’t live in the vacuum of space). Hospitability is not the be all and end all of life because life itself relies on a complex mixture, an atmosphere, which includes domains (or elements) that are inhospitable to life. Inhospitability and hospitality belong together like a horse and carriage, like sun and earth.

True enough, given that this hospitable earth is our home and its well-being should, therefore, occupy much of our thoughts, passions and actions but, even so, at the same time we must not forget that it’s very hospitability is always already dependent on being part of a mixture that includes the inhospitability of the sun as a raging star (after all we can’t live on — or too near — the sun) and the inhospitability of the space that exists between it and us (we can’t live in the vacuum of space). Hospitability is not the be all and end all of life because life itself relies on a complex mixture, an atmosphere, which includes domains (or elements) that are inhospitable to life. Inhospitability and hospitality belong together like a horse and carriage, like sun and earth.It would seem that to be true (philosophically, scientifically and spiritually) to the mixture that is the complex reality of our lives we need to find ways simultaneously to be creatures of both the earth and the sun. Our quite reasonable fears for the future of the earth should not blind us to the fact that if we are to save the “hospitable” earth wisely then we need to ensure we become creatures that live as much by the truth of the “inhospitable” sun as we do by the “hospitable” earth.

This thought made me feel it was clearly time for another sip of beer. Refreshed and fortified, I read on and came upon the passage you have already heard in which Coccia reminds us we have for too long “conceive[d] of ourselves through the prism of a falsely radical model” (p. 91) and that this, in turn, “has an enormous price: it means devoting oneself to the night, to chose to think without the Sun.” Coccia goes as far as to say that it seems that centuries ago philosophy chose “the way of darkness” (ibid.).

This thought made me feel it was clearly time for another sip of beer. Refreshed and fortified, I read on and came upon the passage you have already heard in which Coccia reminds us we have for too long “conceive[d] of ourselves through the prism of a falsely radical model” (p. 91) and that this, in turn, “has an enormous price: it means devoting oneself to the night, to chose to think without the Sun.” Coccia goes as far as to say that it seems that centuries ago philosophy chose “the way of darkness” (ibid.).To correct this Coccia encourages us to think about how plants live. Earlier in the book he gives us a little thought experiment to help us do this, so, let’s do it now. He points out that the plant is ecologically and structurally double in that they move both towards the sun and dive down into the dark earth. So now

Imagine that, for each movement of your body, there is another one that goes the opposite way; imagine your arms, your mouth, your eyes have an antithetical correspondent in a matter that mirrors perfectly the one that defines the texture of your world: you would then have an idea, albeit a vague one, of what it means to have roots (p. 82).

It seems to me that what Coccia is trying to do through this thought experiment — and in the reading from the book we heard earlier — is encourage us to develop new metaphors to live by. Now you might be tempted to think that this kind of activity is merely to be fiddling (or philosophising) while Rome (or the Earth) burns. But is it really?

Let’s not forget the work of the film-maker with the U.S. Forest Service, Steve Dunsky to which I have introduced you a few times. You’ll perhaps remember that he talks about the need for our restoration of the world to be preceded (or at least intimately accompanied by) a need to “re-story” the world. As he pithily says in a short essay he wrote in May 2015 “[b]efore we make new policies, we need new metaphors” and he goes on to note that:

Humans constantly generate new words, and those words continually shape us. We are haunted by language. We are the stories we tell each other and ourselves. And when we fall into despair, we dip into the wellspring of literature, music, and art to be reinvigorated.

This is why Dunsky got involved with an eco-cultural conference called “The Geography of Hope”. For him, such events help to “bend our consciousness and refresh our lexicon” and this is the reason writers and artists have played a crucial role in conservation history. As Dunsky asks: “Where would the movement be without the literary talents of [Henry David] Thoreau, [John] Muir, [Aldo] Leopold, [Wallace] Stegner, and [Rachel] Carson?” To this eminent list I would add Emanuele Coccia.

Anyway, I cannot but help strongly feel that if we carry on trying to do the work of environmental restoration without simultaneously working on a re-story-ation of our world then we’ll just be working out of the same paradigm that got us into trouble in the first place. We truly do, in fact, live by metaphors and I think it matters what metaphors we choose to use or simply inherit without any thought or reflection.

Think, perhaps, of some of the metaphors for the human condition we have connected with coal-burning, earth-destroying steam engines. “Full steam ahead”; “getting up a full head of steam”; “letting off steam” and so on. How could our lives be changed were we able to draw our metaphors relating to our movement in the world, our feeling of being full of energy or needing to let go of our anger, from plant life?

It is, of course, hard to say before hand but surely, in this more ecologically aware age that is in a climate emergency, an intentional project of re-story-ation that uses metaphors drawn from the life of plants is going to be more appropriate, healthy, holistic and helpful than to continue to live by metaphors drawing on, in my example here anyway, the burning of fossil fuels?

It is something like this kind of re-story-ation that I am sure Coccia is trying to achieve; it is to help us, via a reflection on the life of plants, to help us see and feel our true place in the whole universe where everything is always already influencing and interpenetrating everything else; to see and intimately that, just like a plant (and everything else) we are as much a being of the stars (in particular the Sun) as we are of the Earth. As Coccia says, this gives us a new and wholly naturalised kind of “astrology”:

This is not, or not only to make the simple assertion that the stars influence us, that they govern our life, but to accept all this and to add that we also influence the stars, because the Earth itself is a celestial body among others, and everything that lives on it (as well as in it) is of an astral nature. There is nothing but sky, everywhere, and Earth is one of its portions, a state of partial aggregation (pp. 91-92).

And isn't this precisely what we need today? — a new nexus (or mixture or aggregation) of metaphors to live by that reflect the interconnectedness of natural world as we now know it through our natural sciences and ecophilosophies instead of continuing to live, as we seem to be, by our old metaphors based on a supernaturalist and capitalistic world view that has only served to make us to live in ways that encouraged an often violent and destructive dominion over the natural world?

And isn't this precisely what we need today? — a new nexus (or mixture or aggregation) of metaphors to live by that reflect the interconnectedness of natural world as we now know it through our natural sciences and ecophilosophies instead of continuing to live, as we seem to be, by our old metaphors based on a supernaturalist and capitalistic world view that has only served to make us to live in ways that encouraged an often violent and destructive dominion over the natural world?Dunsky is surely right and that before we make new policies, we need new metaphors and my vote is for us to see what happens if we drew those metaphors from the life of plants.

With that thought, I finished my beer, and began to make my way home across the meadows grateful to, and in the company of, countless, inspirational, breath and life giving plants pushing up to the sun and diving down into the earth. And every step along the way I tried to imitate their way of being in the world to see what it felt like and, I have to say, it felt right.

|

| The Cambridge Unitarian Church as a café during the Open Gardens event |

|

| Some of the gardeners gathered afterwards for a celebratory drink |

Comments