For the good of all let’s cancel our subscription to the resurrection—A reflection for the Easter Weekend of 2020

READINGS:

READINGS:Matthew 27:33-56

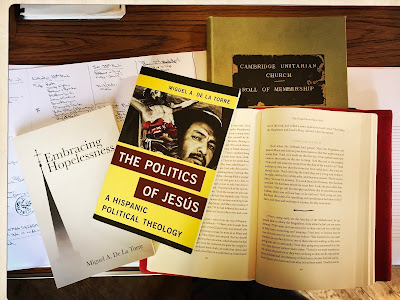

‘Toward A Theology of Hopelessness’ by Miguel De La Torre

Following on from this reading (and I ask you please do take the time to read it) I need to add some words from the blurb of De La Torre’s book ‘The Politics of Jesús’ to explain why, throughout the piece which follows, I spell Jesus’ name in it’s Hispanic form as Jesús:

While Jesus is an admirable figure for Christians, ‘The Politics of Jesús’ highlights the way the Jesus of dominant culture is oppressive and describes a Jesús from the barrio who chose poverty and disrupted the status quo. Saying “no” to oppression and its symbols, even when one of those symbols is Jesus, is the first step to saying “yes” to the self, to liberation, and symbols of that liberation. For Jesus to connect with the Hispanic quest for liberation, Jesús must be unapologetically Hispanic and compel people to action. The Politics of Jesús provocatively moves the study of Jesús into the global present.

—o0o—

For the good of all let’s cancel our subscription to the resurrection—A reflection for the Easter Weekend of 2020

Three weekends ago my words for reflection included the following paragraph, written, I can now reveal, with this Easter weekend (and also De La Torre’s Latina/o political theology) very much in mind :

Given that such a global pandemic hasn’t occurred since 1918 (and never under the conditions that currently obtain in our modern, inter-connected, hyper-mobile world) it is surely right to say that thinking about what this event means cannot occur before our experience of it. Consequently, it seems to me that, before I even vaguely begin to think about (let alone speak or write about) what the current situation means or will mean, or what I believe (or hope) will (or should or may) come afterwards etc., it’s vitally important for me, for us all, properly to enter into this experience now and so allow it to teach us some necessary lessons.

So how does this paragraph relate to Easter?

Well, one major problem with Easter (aside from the fact that no one, neither Lazarus, Jesús, nor anyone else has been, or will ever be, resurrected from their graves) is that it is a story which has now been imaginatively walked through by us for some two-thousand years. This means we all always-already know the hopeful/joyous end of the story even before the grim story of ‘Holy Week’ starts. The consequence of this is that in our Easter recollections the intense grief and pain triggered by the political and religious violence of the Good Friday execution and the consequent experience of abject loss and despair felt on Holy Saturday are all, in truth, (pre)erased by the (fore)knowledge of the (putative, already) fulfilled hope and joy of resurrection on Easter Sunday and the ascension into the safety of heaven forty days later.

To return to my own paragraph quoted above, the consequence of all this is that the events of Good Friday and the empty and depressing aftermath on Holy Saturday are never fully entered into by too many people (especially those who, like me, live middle-class lives of relative, but still privileged, comfort and job/financial security). Another way of putting this is to say that culturally/religiously nearly all our privileged, middle-class thinking about the events of Good Friday and Holy Saturday are had before our experience of them. But I hope you can see that this is not the way the world actually works.

Taking the Easter story for a minute as if it were literally and historically true, we need to be aware that the first disciples would have experienced Good Friday and then Holy Saturday without any (fore)knowledge of the resurrection of Jesus on Easter Sunday. In consequence, we need to be acutely alert to the fact that, for them, Easter Sunday had absolutely nothing to contribute to how they were to live through Good Friday and Holy Saturday, except and only retrospectively when it was too late for it to have had an effect upon how they had, in fact, dealt with those earlier times. The hope and joy of Easter Sunday (whatever we think that was/is and whether it was/is even vaguely plausible) could never have been of any help to Jesús and the disciples as they found themselves actually living through the shock, pain and despair of what only later became known in the tradition as Good Friday and, for the disciples anyway, Holy Saturday.

Now, today, we find ourselves in the midst of an event that — especially given the time of year when it is occurring — feels like it might meaningfully be called a kind of collective Good Friday. All around us hundreds of thousands of innocent people are getting very sick, many hundreds of thousands of key workers are selflessly risking their lives, many thousands more of whom are dying and many of whom (along with their surviving friends and relatives) are going to feel as utterly ‘godforsaken’ and hopeless as Jesús felt on the cross, and the disciples felt at the shocking death of their teacher and exemplar.

To keep close to the events of the story as it is told in the synoptic gospels, the political and economic responses to this pandemic have also meant that, before our very eyes, we are seeing the veil in our culture’s own preferred temple, the temple of Mammon, effectively being torn in two (i.e. it’s coherence — always in doubt — is being rent wholly asunder). Also, as the foundations of that temple start to shake violently we are also seeing shocking fractures all over the place in the very fabric of our societies and we are suddenly experiencing a very real kind of darkness coming over the whole land.

But, as I write this reflection for you (on Maundy Thursday), let’s not forget that, as yet, we’re nowhere nearly through this Good Friday event — at the very best we’re only at its ’sixth hour’ (three in the afternoon) — and our walk through this ‘valley of the shadow of death’ is going to carry on for many weeks, if not many months, yet.

Neither must we lose sight of the fact that when we have left the immediate environs of the valley of the shadow of death we will only have been brought into the desolate landscape of our own kind of Holy Saturday. To be clear, this is a ‘place’ and ‘day’ (though in truth it is likely to stretch over the course of many months, if not years) that is going to be exceptionally difficult for everyone, but especially those who were in highly marginalized and precarious positions before our own Good Friday dawned. The truth is that all of us are going to experience a very long period of considerable confusion, despair, depression (mental and financial) and hopelessness as we all try to find ways to move forward into new kind of life together.

And, lest it is not yet clear to you, I am saying (though I fervently wish I did not have to) that we, just like those first disciples, have absolutely no way to draw strength from some putative coming ‘Easter Sunday’ that will, somehow, make everything suddenly alright and give overarching, historical and cultural meaning to our current experiences of these dark days.

Easter Sunday (actually, any future day) simply cannot be parachuted into beforehand and we can only enter into it (whatever kind of day it might eventually turn out to be) in so far as we have first actually passed through and learnt how to live fully, lovingly, compassionately, decently and honestly in Good Friday and Holy Saturday and wholly without access to some putative, coming Easter Sunday’s comforts or hopes.

In short, for anyone who is truly living in and through an actual Good Friday/Holy Saturday event, the proclamation beforehand of some already known Easter Sunday hope has, is, and always will be, merely an occasion for the selling of snake-oil. Consequently, along with Jim Morrison of The Doors in his song, ‘When The Music’s Over’, I hereby announce that, personally, I have finally ‘cancel[led] my subscription to the Resurrection.’

It seems to me that if I, you, any of us, truly want to live a life genuinely modelled on the life of Jesús — a person who always knew exactly who were (and what was) truly ‘key’ in any decent society (let those with ears, hear) — then we must start to live a real, Jesús-like life in this, our own Good Friday and coming Holy Saturday and we must do this, to repeat, wholly without the hope of some coming Easter Sunday.

Truly letting go of Christianity’s Easter Sunday hope may, counterintuitively, turn out to be some genuinely faint anticipation of Sunday’s Good News because it may mark the moment when we finally make a decisive, genuinely neighbourly, this-worldly turn (i.e. metanoia or repentance) towards the many hundreds of thousands of marginalised, powerless, hopeless and dying people who were, are and always will be those who are the key people in the kingdom preached by Jesús. As a society we need to turn towards, affirm and help uplift these people and support them without exception and to the very limit of our strengths and resources (in the fashion they tell us they wish to be affirmed and uplifted and not merely as we would wish) and, when we finally move into our own Holy Saturday, then we must continue to ensure that these same people are made secure and valued as the key people they truly are. What we must not do — and what we already know — is to allow our societies to return to the wholly unjust and destructive political, financial and economic models that obtained before the coming of these dark days. As Miguel De La Torre reminds us, it ‘may be Saturday, but that’s no justification to passively wait for Sunday.’

As I finish writing these words, very close to the bedside of my wife’s dying daughter (trying my best to support them both and her other children through this time), I am powerfully struck by how Christianity’s Easter Sunday has always served to take our eyes off what Jesús was always truly teaching us, namely, to see clearly that everything, but everything must be dissolved into the call to justice and charity to one’s neighbour and that the doctrine of the kingdom taught by Jesús meant that henceforth and forever God was, is and will be present only in and as one’s neighbour.

So, may I humbly and passionately suggest that we all cancel our subscriptions to the resurrection of Easter Sunday and it’s associated false hopes and, instead, finally see, as Jesús always saw, that God (whatever one means by the word God) is only to be found on this earth in the here and now and insofar as we learn to show love, justice and compassion to each other, to all our neighbours and enemies without exception.

Comments