A further meditation upon the Cambridge Unitarian Church's history and its relevance for us today

|

| My study wall ready for replastering and re-painting |

THE GREEN STREET ROOTS OF THE CAMBRIDGE UNITARIAN CHURCH

As some of you know, in December of last year, I was forced to vacate my study because water from the poorly constructed and maintained gutters on the building next door began significantly to seep into the room. It was only last week that the work of repairing and redecorating the study was finally finished. “Alleluia!”, say I, and my thanks go out to the committee for helping to progress this work — work that was, naturally, massively delayed by the arrival of the pandemic amongst us. My especial thanks go to our treasurer, Stephen Watson, who had to deal with our, not always helpful, insurers. Without his sterling work I would not be able gratefully to have started moving back into my study during last couple of days.

|

| My study, damp, sorry and abandoned |

|

| The Common Room, my temporary desk and some of my associated clutter |

When I first read them myself I was reminded of a meditation I wrote for you back in February 2019 which drew upon that period of our history to explore the, to me, very strange case of our church’s altar/table. Should you wish to you can read this address by clicking on the following link: “When is a table not a table? When, perhaps, it's an altar?—Some Christian a/theist thoughts inspired by Heidegger and Bonhoeffer.”

Now most of what appears in the accounts of our church’s opening I already knew about but I did not know about one major bit of information it contains, namely, something about the early history of our church in Cambridge.

|

| F. J. M. Stratton (in the middle) surrounded by former ministers of the congregation and, for a little while longer anyway, the Beach Boys, the Beatles and Miles Davis. What would he think? |

“The Unitarian Church was formed in 1680, and met in a chapel in Green Street until 1818, when the lease of the building fell in.”

Was this true? Given we’re still in lockdown I cannot, of course, get access to any libraries but various bits of initial, intriguing information can be gleaned on line.

I searched, firstly, for a chapel on Green Street in Cambridge and was immediately directed to the wonderful Capturing Cambridge website run by the Cambridge Folk Museum. That site tells us the following piece of information:

“History of 5 Green Street: On the site of the houses numbered 5, 4, and 3 stood an old Independent Chapel, dating back to 1688, generally known as the Old Green Street Meeting House, but later referred to Stittle’s Chapel, after the Rev John Stittle, who served his congregation here from 1781 until his death.”

Naturally, I next searched for some information on the Rev John Stittle and was directed to the webpage of the Eden Baptist Church which is now located in new buildings on Fitzroy Street almost opposite Waitrose and Greggs. Before going on you should know that this church is an extremely conservative, Biblically fundamentalist one and, in my twenty year long engagement in ecumenical circles in Cambridge, I have never once encountered anyone from the church. It should be clear that if the orthodox Christian churches on the ecumenical scene are so completely shunned by the Eden Baptist Church then we Unitarians are deemed to be irredeemably beyond even that pale. Naturally, the differences that exist between our respective churches will come as no surprise to any of you but, as you will see in a moment, the huge differences may well have a very local, shared church roots. As the old adage goes the most bitter and long-lasting arguments are those had within the same family . . .

So, the Eden Baptist Church website informs us that in 1669, in the Green Street home of a certain Elizabeth Petit, a congregation had begun to meet and it was they who built a meeting house there in 1688 which, following the Act of Toleration in 1689, finally became a legally constituted church. The website continues:

A few years later this congregation moved to a building on the other side of Green Street and a group of Stittle’s followers began renting the original Meeting House in their place. This is the group that was to go on to become Eden Chapel. The link between Stittle and Eden is testified to by the re-interment of Stittle’s remains at Eden’s new chapel some years later, when they were disturbed by the redevelopment of Green Street.

The text above is infuriatingly ambiguous and does not make it clear whether it was those who stayed in the meeting house or those who “crossed the road” were the group that eventually formed the congregation which became the Eden Baptist Church. Stratton’s text reveals that he thinks it was the latter group because in his mind those who stayed in the meeting house were the Unitarians (or were at least meaningfully proto-Unitarian/Socinian). Hmmm, some serious digging and untangling clearly needs to be done here if we are to get to the bottom of this claim. Nor, of course, can we yet rule out that Stratton may simply have been misinformed.

However, what is evident is that some kind of schism occurred in the Green Street congregation and this, in a general, very circumstantial fashion, supports Stratton’s claim because it was just such arguments and splits within Presbyterian, Independent and Baptist congregations that eventually led to the foundation of many of our oldest Unitarian congregations.

All in all, I have found myself gently amused by the emerging possibility that one of the most conservative churches in Cambridge and the most theologically liberal church in Cambridge may be children of the same Green Street Meeting House!

But this discovery (if discovery it really is) also serves to remind me of our own church community’s longer-term trajectory which is so, very, very different from the Eden Street Baptists. As I have occasionally reminded you, in his important lecture of 1920, “The Meaning and Lessons of Unitarian History”, the great Unitarian historian Earl Morse Wilbur (1886-1956) felt that, although a study of sixteenth- to early nineteenth-century Unitarian history (which included the early Green Street period) did at first sight appear to teach us that the principal meaning of the movement had been “a purely doctrinal one” and that the goal at which we aimed was “nothing more remote than that of winning the world to acceptance of one form of doctrine rather than another”, the truth was actually very different. When he surveyed the whole of our history up to 1920, Wilbur felt sure that the “doctrinal aspect” of our churches was in fact only “a temporary phase” and that Unitarian doctrines were only “a sort of by-product of a larger movement, whose central motive has been the quest for spiritual freedom.” Indeed, his essay begins with a clear statement that “that the keyword to our whole history . . . is the word complete spiritual freedom.” The conclusion he delivered to his own day was that, thus far, we had hardly done anything more than remove certain “obstacles which dogma had put in our way” and had only just begun to “clear the decks for the great action to follow.”

Like our own Cambridge Unitarian Church forebears, for Wilbur, this “great action” was to create a relevant, liberative, free-thinking version of — or, perhaps, meaningful and genuine successor to — formal, conservative, doctrinal and belief-led Christianity, the kind of Christianity which our (apparent) cousins at Eden Baptist Church have only doubled-down upon.

|

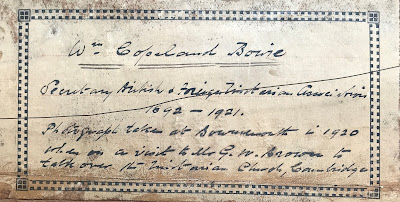

| Photo of William Copeland Bowie (1855-1936) that, once again, hangs in my study. |

|

| Label on the reverse of the photo above (click on this to enlarge) |

“It is a ‘Modernist’ Church that we would dedicate to-day. Whatever of wisdom, truth, and beauty the past has bequeathed to man, here may it be sincerely treasured and loved. Here, too, may the larger knowledge and the enriched experience of the living present receive ready and eager welcome. Above all, may the vision of a nobler world be kept always bright and clear and the door never be closed against any fuller, more perfect revelation of the Divine purpose and will which the future may have in store for the children of men.

“May the strength and beauty which the architect and the craftsmen have imprinted on this building have their spiritual counterpart in the strength and beauty of the religious faith which as the years come and go will find expression within these walls.”

Now, me being me, I’d want to undertake with you a critical, forensic break-down of Bowie’s text and, in particular, to explore in depth what he meant (and how we, today, might radically reinterpret) the meaning and implications (then and now) of the terms, “God” (see, for example, in my address linked to above about our altar/table), “Christ”, “Modernist”, “Divine purpose” but, speaking personally, I can say without any hesitation at all, that I still find Bowie’s words pretty much spot on. Indeed, I write this thanking my lucky stars that I was called by this congregation to be the minister of a church which was opened with such still relevant, far-seeing, open-hearted, open-minded and deck-clearing words.

|

| The site of the Cambridge Unitarian Church before its construction in 1927, the current Manse to the right . . . with added sheep! |

NB. After writing this piece some further information came in my direction which significantly fills out the story. You can read that piece at the following link:

THE GREEN STREET ROOTS OF THE CAMBRIDGE UNITARIAN CHURCH

Comments

Thanks once again for your kind words. I hope you find some other stuff that does, indeed, inspire a few thoughts. I trust all remains well with you.

Warmest wishes as always,

Andrew

I'm not sure of the date of the map, relative to the congregational split. If what it shows as the Meeting House is the original meeting house, that would place Sainsbury's on the continuing Baptist site and the Edinburgh Woollen Mill on the budding Unitarian site. But I suppose it might be the other way round ...

Fascinating, anyway. Thank you!

Your conjecture about which group eded up as Eden Baptist Church is correct as this follow-up piece of mine will show. I hope you enjoy it.

All the best, Andrew.

THE GREEN STREET ROOTS OF THE CAMBRIDGE UNITARIAN CHURCH