L’chaim! — to life!: A religion without God and an ethics without absolutes—A short Easter Sunday reflection

A short “thought for the day” offered to the Cambridge Unitarian Church as part of the Sunday Service of Mindful Meditation

(Click on this link to hear a recorded version of the following piece)

—o0o—

Last year, whilst we were still in lockdown, I offered you my Easter reflections only via my blog and podcast. Should you want to read or listen to that piece it was called “Cancelling my subscription to the Resurrection and truly living the death of God”, and you can find links to it in all the usual places. What I am offering you here is simply the central idea it contained.

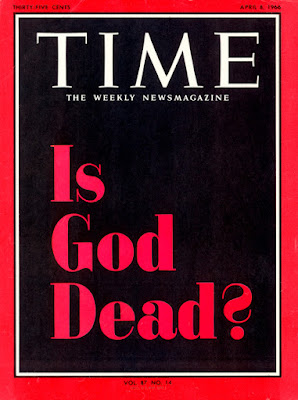

To begin it’s important to know that the theological position from which I am writing — one which, given the free-thinking ethos of this church community, I must stress none of you is obliged to share in any way — is known as “death of God theology” or, rather less shockingly, “radical theology” which developed in America and Europe from the mid-1960s on.

Now a lot of people assume this is going to be a very nihilistic and negative position, but I think the opposite is true and, to pick up on my words for you last week, to my mind it is the only theological school that can render coherent in our modern age key aspects of the Christian tradition and so keep alive some of its most important hopes for the creation of a better world for all.

A central idea in this school of thought is that of “self-emptying” — in the New Testament the Greek word is kenosis and it’s found in Paul’s short Epistle to the Philippians (2:6-8):

“[Jesus] . . . subsisting in God’s form, did not deem being on equal terms with God a thing to be grasped, but instead emptied himself, taking a slave’s form, coming to be in a likeness of human beings; and, being found as a human being in shape, he reduced himself, becoming obedient all the way to death, and a death by a cross” (trans. David Bentley Hart).

It’s worth knowing that in our own tradition this idea was first drawn upon by two important eighteenth-century Unitarians, namely Thomas Belsham (1750–1829) and Joseph Priestley (1733 –1804), but the key modern figure who drew upon it was Thomas J. J. Altizer (1927-2018) who only died in 2018. Altizer thought that the transcendent creator God of monotheism had not merely temporarily self-emptied into the human form of Jesus but, by actually dying on the cross, had wholly and permanently self-emptied into the world. Now, without going into whether or not this self-emptying quite literally occurred on the cross, many people who follow Altizer’s lead, including me, tend to take that moment on the cross mythopoetically as the first expression in human history of the idea that whatever the word “God” can mean (or might) for us today, it is a word which can only speak of God as totally present as absent; or, to put it slightly differently, that absence is today the presence of God. As one of Altizer’s colleagues, Mark C. Taylor, puts the matter, this means “the disappearance of God turns out to be God’s final revelation.” (Mark C. Taylor in the introduction to “Living the Death of God” by Thomas J. J. Altizer, SUNY Press, 2006, p. xv).

In the context of Easter, the important thing to grasp is that for the radical theologian everything of metaphysical importance in the Christian myth, happens, not on Easter Sunday, but at the moment of Jesus’ death on Good Friday. In that mythopoetic, self-emptying moment, all of Christianity’s former supernatural God-talk, superstitious and apocalyptic ideas are finally and forever dissolved into the simple, if always infinitely challenging, existential, ethical demand made by Jesus, to show justice and love to our neighbours, enemies and all creation, right here, and right now.

The positive consequence of a kenosis-inspired understanding of the Christian story, to quote Mark C. Taylor once again, is that:

“In [our modern] world where to be is to be connected, absolutism must give way to relationalism, in which everything is codependent and coevolves. After God, the divine is not elsewhere but is the emergent creativity that figures, disfigures, and re-figures the infinite fabric of life. A religion without God issues in ethics without absolutes to promote and preserve the creative emergence of life across the globe”(Mark C. Taylor, “After God”, Chicago University Press, 2007, p. xvii-xviii).

I cannot, of course, speak for you — and nor would I ever dream of trying — but for a Christian atheist like me, although Easter Sunday is not a celebration of the resurrection, it most assuredly is a celebration of a radical new beginning (cf. the work of D. G. Leahy) in which a new, ethical way of being-in-the-world finally emerges.

So, on this Easter morn, I raise a glass to this new beginning with an ancient Jewish toast that Jesus himself would have known:

L’chaim! — to life, across the globe!

Comments

Thanks for your kind comment. I'm very glad that it spoke well to you.

Aloha nui loa,

Andrew