Religion in the non-religious world

A pdf of the revised order of service in which this address was given, and about which it speaks, can be found at this link.

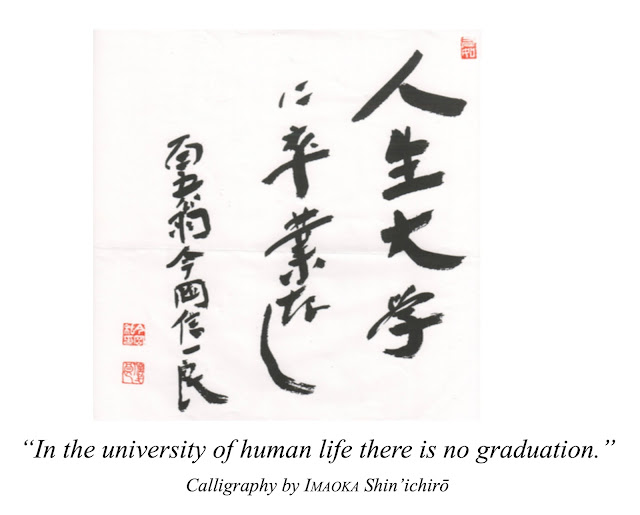

One Sunday morning in Tokyo, sometime in 1973, at a meeting of his small, free religious community, Kiitsu Kyokai, Imaoka Shin’ichirō gave a brief talk on the subject of “Religion in No Religion” (see pictures at the end of this post for the Japanese version of the text of which a solid English translation has not yet been made).

I thought it would be interesting to bring to your attention the central insight of this piece because he was speaking of something that is clearly highly relevant to our own time and place. It also the opportunity to add something to the valuable conversation nine of us from the Cambridge Unitarian Church began on Wednesday evening about Imaoka sensei’s idea of free religion.

But before coming to the central insight of his 1973 talk, it’s helpful to explore a couple of other things first.

I’ll start with the name of Imaoka sensei’s group, Kiitsu Kyokai, which was often mistranslated as the “Unitarian Church.” This came about for two related reasons.

The first is because, between 1917 and June 1921, Imaoka sensei was the last secretary of the Japanese Unitarian Mission and the Japanese Unitarian Association (CS, p. 88).

The second reason is that because of this historical connection to Unitarians, it seemed natural that, since the word “Kiitsu” ( 帰一 ) means “oneness” or “unity,” and “Kyōkai” ( 協会 ) has the meaning of “assembly” or “association” — albeit with an emphasis towards the meaning of “school” where one gathers together with others in order to learn and grow — this could simply and unproblematically be rendered into English as, “Unitarian Church.”

But one of the many fascinating things about Imaoka sensei and, indeed, many of the other Japanese figures associated with the Unitarian Mission and Association in late-19th and early 20th century Japan, was how quickly they saw that the basic Unitarian position with, on the one hand, its commitment to the idea of an underlying interdependent unity of all things and, on the other hand, to critical, free-thinking as well as an openness to other ways of thinking about and being in the world, that this could be opened up into a much broader, universalistic, conception of religion than that which was held by the American or British Unitarians of the time, who still understood it as a liberal form of Christianity. So, it’s important to know that from the outset the Japanese yunitarian movement (which, when transliterated, is spelt with a “yu” at the beginning rather than simply the letter “u”), always contained a mixture of Unitarian Christians, New Buddhists, liberal Shintoists and religious progressives and radicals.

Imaoka sensei’s own life mirrored this diversity and, over 106 years he, in turn, personally engaged with and continued highly to value, liberal Christianity (especially in its Unitarian form), Buddhism (especially Shin Bukkyo, or New Buddhism) and Shinto. And, in an essay entitled, “A viewpoint on free religion,” also from 1973, he was able to state, quite clearly, that:

“I do not feel it to be a contradiction to be a Christian, a Buddhist, and a Shintoist at the same time. The three are not one, however, having quite different characteristics and individualities, but all of them exist in me, supplementary to each other” (SW, p. 106).

Given all this, I hope you can see that his own, post World War II community called Kiitsu Kyokai was always a post-Unitarian, free religious one, concerned only to follow truth wherever it may lead.

But, Imaoka sensei was also clear that, despite the vital importance of a

rational, critical approach to religion, such a meeting of free

religious people was always best when carried out after a time of

meditation. Consequently, every Sunday morning, before the service and

his short address, he would lead a time of quiet sitting, i.e. Seiza meditation, to which some of you were introduced a few weeks ago by my friend, Miki Nakura sensei.

Imaoka

sensei practised Seiza mediation for 78 years from 1910 until his death

in 1988, saying that, for him, meditation was “the source of the

autonomous creative vitality” for both his “body and his spirit” and that

when he meditated he felt “that the heavens and earth are one with the

universe” (SW, p. 45). In 1985, just three years before his death, he

revealed that:

“In my house there is no Buddhist or Shinto

altar. Also I do not read the Bible and pray as a daily routine the way I

did as a Christian. However, I cannot stop doing meditation. I can say

that meditation is the only religious life that I have” (SW, p. 46).

Now, it seems to me that this broader, Japanese yunitarian conception is very helpful to consider in our own pluralistic and cosmopolitan world in which

there is an increasing amount of what is called dual or double belonging

[see HERE and HERE]— something that’s very prevalent in this Cambridge Unitarian congregation.I also think it may be very helpful to consider ourselves as being advocates of

“free religion” rather than adherents to any specific -ism, including

Unitarianism. Embracing the concept of Kiitsu Kyokai—a free religious

community emphasizing meditation alongside lifelong learning, rational

thinking, and conversation—seems to me to provide a more suitable framework for our

modern identity than that of being a church.

So, with that introduction out of the way, and following our own time of meditation, let me now briefly return to the central insight from his 1973 address, “Religion in No Religion.”

In his talk, Imaoka sensei was keen to point out that for him, religion was not some special way of life, but something which existed where and whenever human beings try to live in a humane way. As he reminded his audience, “in Japan, before the Meiji era, there was no word for religion, just the way” (道 michi/tao) and that “the way” was not only to be found in Buddhism and Shintoism, but in tea, swordsmanship and the arts and crafts. Indeed, all secular professions, whether doctors or farmers, all had their own paths.

In short, Imaoka sensei felt that one of the key aims of free religion was to remove the boundary wall between religious life and secular life and to show that religion did not only exist when a person went to temples or churches.

Like many of us here today, Imaoka sensei felt that true religion, by which he meant a genuinely free and inquiring religion, was becoming increasingly hard to find in traditional religious institutions. However, despite this, in his own long career as a teacher and principle of a middle and high school called the Seisoku Academy — he had discovered that it was “surprisingly common for true religion to live outside churches and temples” and that there were many, many people who, although they said they were “non-religious”, were nevertheless earnestly seeking for answers and responses to the perennial religious questions concerning the meaning of life and death that face every human being.

This is, of course, something we in this community are also increasingly recognising, and we know that, somehow, we have to find a way to offer ourselves and others a free and inquiring religious community that is able to speak to the broadly secular person who sees themselves as non-religious and who finds traditional church and temple-based religion so off-putting because it is precisely in churches and temples that they are not finding true religion!

This is one of the reasons Imaoka sensei put such stock in creating a free-religious and free-thinking community that understood itself as offering opportunities for lifelong learning and conversation where people could “earnestly pursue learning and art and where there is a life in which souls are in contact with each other.” For Imaoka sensei, “Real education is always just religion” and, by the end of his life, for him the distinction between religion and ordinary life had simply disappeared, and he was clear that, whether through political activities, educational projects, art or academic work, agriculture, commerce or industry, if a person “seek[s] a purpose in life and pursue[s] the meaning of life and the human truth” they “will definitely find something more than human” and “come across the existence of something greater than the self.” When we do this, he thought that,

“We come to realize that there is more within us than we are, and that it is like an underground root that connects us all.”

Isn’t Imaoka sensei’s vision of a free and inquiring religion, in which the boundary wall between religious life and secular life is removed, precisely what we are hoping to express in this community and to pass on to the wider world? It seems so to me . . .

Comments