It is human to have compassion for those in distress

(Click on this link to hear a recorded version of the following piece from October 2023)

In the dark and darkening days we find ourselves entering ever more deeply into — both geopolitically, environmentally and in terms of the season — a perennial question arises for a small community such as this one which is attempting to offer the world a contemporary, creative, “free-spirituality” or “free-religion,” what the twentieth-century Japanese Unitarian, Imaoka Shin’ichirō-sensei (1881-1988) called “jiyū shūkyō” (自由宗教). The question is: what of immediate benefit can be found by a person who seeks us out?

But before I address that question directly, just to remind you, a few weeks ago using Imaoka-sensei’s own writings, I defined “jiyū shūkyō” (自由宗教) as something in which,

“ . . . together, in community, people are able freely to interpret critically various religious beliefs and claims, can find freedom from rigid, authoritarian hierarchies, can freely incorporate diverse religious elements into their own and the community’s faith and practise and, as I so often talk about, can claim the all important freedom to be tomorrow what we are not today.”

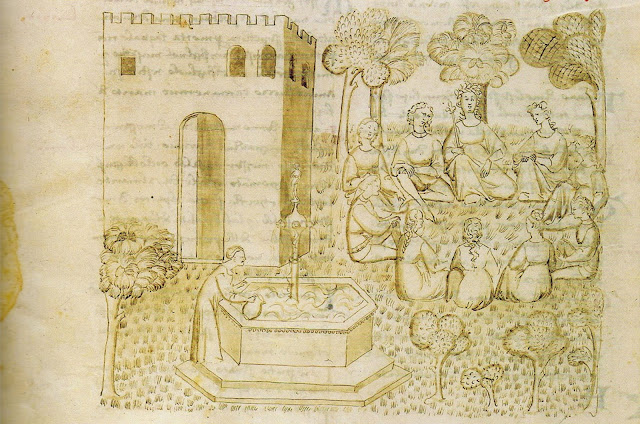

OK, keeping this definition in mind, I think the best way of illustrating my answer to the question of what immediate, benefit can be found by a person who seeks us out, is found via a brief consideration of the Italian, Renaissance poet and humanist, Giovanni Boccaccio’s (1313-1375) famous work, “The Decameron.” Some of you will know I’ve brought this illustration before you a number of times since 2014 but, since we have among us a few new members and attenders who won’t have heard it before, the time seems right to bring it back firmly into view lest it be forgotten.

The year is 1348 and a terrible plague is running unchecked through Florence and, as the professor of Italian Literature, Robert Pogue Harrison, reminds us:

“In the city, civic order has degenerated into anarchy; love of one’s neighbour has turned into dread of one’s neighbour (who now represents the threat of contagion); the law of kinship has given way to every person for himself (many family members flee from their infected loved ones, leaving them to face their death agonies alone and without succour); and where there was once courtesy and decorum there is now only crime and delirium” (Gardens: An Essay on the Human Condition, University of Chicago Press, 2008, p. 84).

To escape this horror, a group of seven young women and three young men decide to leave the city for two-weeks and retreat to a secluded villa within a wonderful walled-garden and there “to engage in conversation, leisurely walks, dancing, storytelling, and merry-making [all whilst] taking care not to transgress the codes of proper conduct” (ibid., p. 84). What could be more different from the horrors of Florence than this garden sanctuary? However, as Harrison points out:

“While their escapade is indeed a ‘flight from reality’, their self-conscious efforts to follow an almost ideal code of sociability during their stay in the hills of Fiesole are a direct response to the collapse of the social order they leave behind. In that respect their sojourn is wholly ‘justified’ by Hannah Arendt’s standards [when she says]: ‘flight from the world in dark times of impotence can always be justified as long as reality is not ignored, but is acknowledged as the thing that must be escaped’” (ibid., p. 84).

Now, a particularly striking element of Boccaccio’s story is that, at the end of their sojourn, the seven women and three men do not decide to remain safely within the walls of their sanctuary but to return to the fray in plague-swept Florence. We may take it, therefore, that their temporary flight was undertaken with the aim of restoring to them some real inner and outer strength so as they might be able to continue to uphold and promote the kind of values that are the very salt of human existence, values that then, and alas now, are so in danger of being thrown out and trampled underfoot, values such as listed by the French philosopher, Michel Onfray:

“. . . friendship . . . love, affection, tenderness, sweetness, thoughtfulness, delicateness, forbearance, magnanimity, politeness, amenity, kindness, civility, attentiveness, attention, courtesy, clemency, devotedness, and all the words carrying a connotation of goodness” (“A Hedonist Manifesto: The Power to Exist”, Columbia University Press, 2015, p. 49).

Our religious community’s history as part of an extensive liberal Enlightenment humanist tradition — one which includes Boccaccio of course — has constantly served to remind us that to be human means to be vulnerable to misfortune and disaster and this, in turn, means we have remained acutely aware that, periodically, we all find the need to withdraw and to be in need of help, comfort, distraction, or edification. We have come to know, too, that our condition is for the most part an affair of the everyday, not of the heroic, and we know that our minimal ethical responsibility to our neighbour consists not in showing anyone the way to redemption but in simply helping them to get through the day.

It strikes me that, without shutting out reality, within the walls of this small sanctuary on Emmanuel Road (as within the walls of the Villa Palmieri in Fiesole) we, too, can be a genuine place of humanization in the midst of, or in spite of, the forces of darkness that now seem to be surrounding us everywhere. In practising jiyū shūkyō we, too, are making self-conscious efforts to follow an almost ideal code of sociability so that we can genuinely help keep our interactions with each other pleasurable through wit, decorum, story-telling, fellowship, conversation and courtesy and always be adding to the pleasure rather than the misery of life.

It is through the practise of jiyū shūkyō that we are, I think, well-placed to offer this kind of support to people without feeling the need to become moralists, zealous reformers or would-be prophets; we can offer people this support without being especially preoccupied with human depravity or humanity’s prospects for salvation; and we can offer this without any need to harangue people from any self-erected pulpit of moral, political, or religious conviction.

Consequently, I have real faith that in our own dark times our light on a lampstand giving light to all in the house may be able to be seen the way we are able to send people back out into the world each week confidently able to display in their own daily lives, the kind of simple, civil humanism of neighbourly love which was beautifully expressed in Boccaccio’s own maxim that: “It is human to have compassion for those in distress” (“Umana cosa è aver compassione degli afflitti”).

So, when someone next asks you, “What’s the point of coming here on a Sunday?”, you now know how to answer. Our continuing task is always to be ensuring that this answer is true and not a mere self-delusion.

Comments