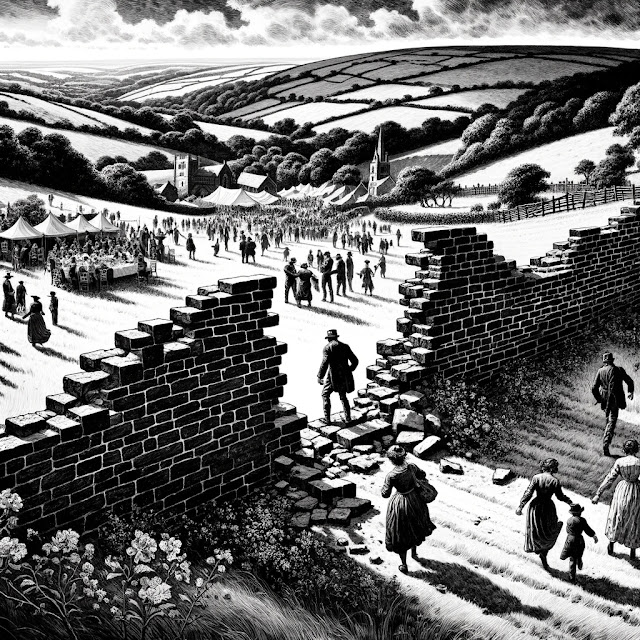

In praise of syncretism, the impurity of all religions, and the tumbling down of walls

At the service in which this thought for the day was given we began by singing a song well known in Unitarian circles by Tracy Spring called, “Walls Come Tumblin’ Down.” It was written in 1996 for the 25 anniversary of the Northwest Folklife Festival in Seattle, as Spring says, “to celebrate the stunning beauty of people coming to the festival from all over the world, gathering to share their diverse humanity through their songs and their dances.”

Singing the song put me in mind of one of the many domains of human life where we really could do with the walls coming tumblin’ down, namely, religion. But one of the problems with religion — or at least the way humans have so often tended to practice religion in the European and North American context which has been dominated for many centuries by creedal, confessional forms of Christianity — is its concern to be something pure in the technical sense we talk about, say, “24-carat pure gold.” In other words, it shudders at the thought that it might be mixed with something other than the “pure gold” it wants to believe it is and so become debased, becoming only 18-carat gold containing only 25 per cent of other metals, or, God forbid, an even lesser carat than that. And, to avoid this mixing with materials other than “pure gold”, I’m sure you realise many religious traditions again and again put up all kinds of walls, ranging from the doctrinal and ideological, to the actual.

But these walls are all utterly futile because the idea that there exists, or ever could exist, some pure, unmixed religion is nonsense, as all religion is something we call syncretic — a word which literally means mixing or lying together. To illustrate my point it's worth remembering the story about the Saints Barlaam and Josaphat or Joasaph which is a Christianized and version of the story of Siddhartha Gautama, the historical Buddha, Sakyamuni. And it remains wonderful to me to know that the name Josaphat is derived from the Sanskrit bodhisattva.

Anyway, although it seems the word syncretic was coined in the Reformation by German Protestant theologians who were attempting to harmonize and bring back together their different groups, as it passed into English, the word has nearly always been used in highly pejorative sense and has come to have the meaning of attempting to reconcile the irreconcilable.

I think it is important to remember that a community connected with the Unitarian movement, such as the church where I am minister, which is explicitly open to religious and philosophical traditions other than the one out of which it was born nearly five centuries ago, i.e. liberal Christianity, that this tradition is continually thought of by many other religious and philosophical traditions as being today dreadfully and catastrophically syncretic, utterly debased and impure, less pure even than 9-carat gold which contains only 37.5% of pure gold.

This kind of belief can lead to some, what seems to me to be, utterly deranged and dysfunctional real-life situations. Let me give you two brief examples from my 24 years as the minister at Cambridge, one at the beginning and one very recent.

When I became the minister at the Cambridge Unitarian Church in 2000 I quickly became involved in something called the East of England Faiths Council, a now defunct regional interfaith body connected with the Blair Government’s plans for regional devolution in the form of regional development agencies. A couple of years into my involvement, their secretary resigned to take on another job, and I was asked whether I would be willing to take on the role. I was delighted and honoured to be asked and said yes. But, just before attending my first meeting, I was telephoned by one of the committee members to tell me that the Church of England bishops on the committee had vetoed my co-optation on the basis that, as a Unitarian minister, I was not a Christian, or at least I was a too impure a Christian. But, I quickly responded, hang on, this is an interfaith body so, surely, it doesn’t matter whether the bishops consider me to be a Christian or not? Ah, the committee member said, it’s not that simple. Go on, I replied. Well, it’s not just that you as a Unitarian don’t any longer belong in the Christian category, neither do they think you belong to any of the other official religious categories recognised by the East of England Faiths Council, so you can’t be the secretary, you simply don’t have a right to a place at the table, even an interfaith table. I was, quite frankly, shocked by this, and it was only when I said that I would take this story directly to the newspapers that a meeting of the offended bishops was quickly arranged, and they eventually grudgingly accepted that, despite my way less than 9-carat purity as a Christian I would be allowed into their Christian box, pro tem — kept at a safe quarantining distance of course — simply so I would be able to take minutes of an interfaith meeting. It’s astonishing, isn’t it?!

My second example is very much more recent, about which I have only recently reminded you. Namely, the Charity Commissioners’ refusal to accept the Cambridge community’s desire to use the following statement as our proposed object:

“The advancement of a free and enquiring religion based on the Liberal Christian heritage which draws also on Radical Enlightenment philosophies, religious naturalism, other religious traditions and humanism; the celebration of life through service to humanity and respect for the natural world; the promotion of religious and racial harmony, inclusivity, equality and diversity.”

So, here is the reason given by the Charity Commissioners for their refusal:

“The inclusion of philosophies, religious naturalism, other religious traditions and humanism in the purpose wording could lead to uncertainty over what the faith is that is being advanced here.”

However, as I hope you realise, in the Cambridge community there is absolutely no uncertainty over what the faith is that is being advanced. The certain faith this community is actively seeking to promote is what the Japanese Yuniterian (sic) Imaoka Shin’ichirō-sensei called jiyū shūkyō (自由宗教), which, as many of you know by now, can be translated as something like “a creative and inquiring, free or liberative religion and spirituality.” It’s a faith that says clearly that no individual religion, or indeed person, is pure and utterly separate from or unmixed with any other religion (or person). And the truth of this faith is, I hope, sufficiently and beautifully illustrated by the story about the Buddha being a Christian saint.

This is because in jiyū shūkyō (自由宗教) there is always clear recognition that true religion and spirituality must always be likened to life which is a continuously unfolding process always-already mixing many things together and taking on some new form or shape. However, Charity Commissioners, bishops and other conservative and traditionalist religious and political leaders again and again seek to turn the dynamic, creative, inquiring, free and liberative aspect of true religion into something static, with clear boundary walls that can be more easily governed, legislated about and policed. And so century after century they renew their attempts to turn forms and shapes of religion and spirituality that should be temporary and relative, always undergoing change and renewal, into forms and shapes that they feel are somehow permanent and absolute.

For me, and I hope for you too, this is why there will always be the need for openly and proudly syncretic and religiously impure communities such as the one where I am minister, places where it is possible, openly and proudly, to raise the banner of jiyū shūkyō (自由宗教), that “creative and inquiring, free or liberative religion and spirituality” which has a deep faith that, somehow, somehow, all the religious walls which continue damagingly to divide humanity can, and perhaps will, in the end, come tumbling down.

Comments