A New Year’s (Decade’s) Resolution?—Be more like Jesus—Some lessons for Unitarian & Free Christians from the Marginal Mennonites and some Trappist Monks

Introduction to the reading

I subscribe to a online group called “The Marginal Mennonite Society” — indeed, I consider myself to be a Marginal Mennonite because I find myself very much in agreement with the spirit of their public declaration. For your information and, I hope interest and enjoyment, we’ll read that in a moment. But, having admitted this affiliation, as a minister on the roll of the General Assembly of Unitarian and Free Christian Churches it seems important to point out why this is neither odd nor in conflict with my formal status as a minster. It is because our own church’s origins in Poland during the sixteenth-century are to be found in exactly the same broad, Radical Reformation, Anabaptist movement that gave birth to the Mennonites — we’re very much brothers and sisters with them. This is no better illustrated than via a study of the Collegiants who contained various members from anabaptist groups across Europe (including Mennonites and Socinian/Unitarians) and who included among its members Benedict Spinoza.

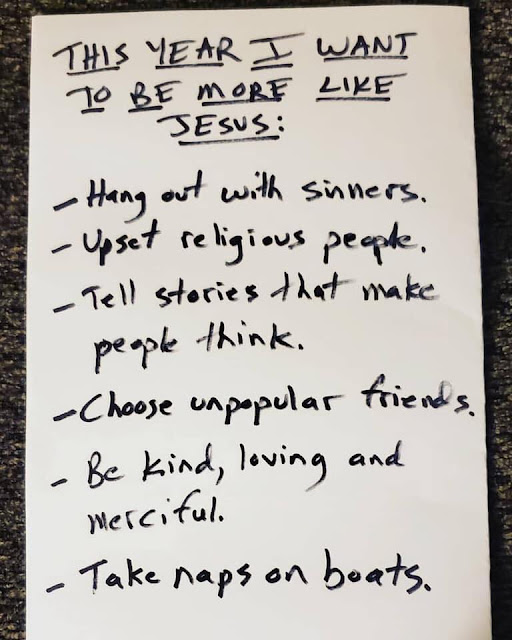

Anyway, the “The Marginal Mennonite Society” is often posting all kinds of interesting information about remarkable people and groups who have lived and still live the kind of life espoused by the group including, now and then, the odd Unitarian, Free Christian and Universalist. But last week they posted the list you have on your order of service that served as the New Year’s resolutions posted (or at least re-posted) by a bunch of Trappist monks living in the hills of central Kentucky in the Abbey of Gethsemani. Some of you may already know of this Abbey because it’s the one where Thomas Merton spent a number of years. I’ll read out that list after we have heard the Declaration.

In 1980 as a fifteen-year old, shortly after beginning to learn the double and electric bass, I managed to borrow two — what were then very rare and expensive — video tapes through Clacton-on-Sea Town Library. One was by the virtuosic jazz bass player Mark Egan, whose playing in the Pat Metheny Group had just recently captivated me; the other was by Rick Danko, whose style of playing was a much, much simpler, rootsy, country blues one. He was the bass player with ‘The Band’ who came to fame thanks to being Bob Dylan’s backing group between 1965-1967. I’d known Danko’s playing for a while because in my first band with my two school-friends, a guitarist called Mark Sainsbury and a drummer called Russell Bettany we were playing loads of Dylan songs and ‘Band’ covers.

Whilst I never lost my love for Dylan and ‘The Band’, as the music in today’s service will reveal, in my professional career I primarily became known as a jazz-bass player and not a country, blues or rock one. But, contrary to what you might expect, I owe more thanks to Rick Danko for this than I do to Mark Egan.

This was because Egan’s instruction video was more concerned to show off his virtuosity and use of high-level, abstract musical concepts and techniques than actually to teach me anything practical whereas Danko’s video was a straight-forward, homespun attempt to show you exactly what he was playing and offer an encouragement to copy exactly what he was doing.

Anyway, in short, I left Egan’s video very impressed at his playing but, essentially demoralised at how far away from that I was and with very little practical information about I might actually learn to play the things he did. On the other hand I left Danko’s video able to play a dozen new things and with a much better basic grasp about what one needed to do as a bass player and real sense that I could be one.

Before moving on to my main subject today it’s important to see that I eventually became a competent jazz bass player, not thanks to Egan, but thanks to assiduously copying what Danko did. The take-away point to pop in your pockets is that copying someone/something does not, necessarily, mean you end up being mere copies of them or it.

Now I tell you this because in my own teaching in the ministry, although I always try to draw into view all kinds of other religious and philosophical figures, I still centre things upon Jesus — indeed, I still consider myself primarily to be a minister of the Gospel of Jesus. There are two basic reasons for this.

The first is situational in that we are a liberal, free-thinking church tradition that was inspired into existence by the man Jesus of Nazareth and because we, the members of this church, still aim to meet ‘in the spirit of Jesus’ and, in the words of an old Unitarian slogan, we continue to try ‘to practice the religion of Jesus rather than the religion about Jesus.’

The second is personal; I joined this church tradition as an ordinary member and then trained as one of its ministers because I was captivated by the example of Jesus as a child and ever since then, in admittedly very faltering and continually unsuccessful ways, I have continued to try to model a life based on his example. In the light of my words so far, one way of putting this is to say that Jesus is for me the ‘Rick Danko’ of religious and political figures. Jesus showed me what, basically, I needed to do to become a liberal, religious, free-thinking person and the way to achieve this was, in the first instance, simply to try to copy his basic religious and political moves through the world just as I tried to copy Danko’s basic moves across the neck of his bass.

Simple.

There are, of course, other figures I and this church tradition might have copied but the human Jesus (revealed by Radical Enlightenment inspired historical, anthropological, archeological, sociological, scientific and philosophical study) is ours and, as a church community that still expressly meets in his spirit, that’s the basic ‘instruction video’ about how to become religiously and politically liberal people I/we have to offer the world.

What I am talking about here is, of course, pedagogy, that is to say, the methods by which certain knowledge and skills are imparted in any educational context.

When I taught music one of my jobs was to impart knowledge and skills to a student in such a way that they could get going as bass-players regardless of whether they finally end up as country, blues, rock, punk, death-metal, thrash, indie or jazz bass players.

In my role as minister/teacher here one of my jobs is to impart knowledge and skills to people who walk through that door so they can get going as liberal-religious people regardless of whether they finally end up as Buddhists, Jews, Hindus, Muslims, Atheists, Humanists, Religious Naturalists or Christians.

It’s important here to recall the point I made earlier, namely, that copying someone/something does not, necessarily, mean you end up being copies of them or it. So, just as I was lucky to inherit Rick Danko as the basic model for teaching bass-playing, I was lucky to have inherited human Jesus as the basic model for teaching a basic liberal religious way of being in the world.

At this point I can now directly turn to how copying Jesus offers us various ways to proceed through what will clearly be a very difficult and challenging decade and century for us all and the, what is to my mind, wonderful list from the Trappists and posted by the Marginal Mennonite Society.

The list outlines some of the things at least one Trappist monk is planning to copy Jesus doing. As I read them through last week, I thought, you know what, that seems to me to be exactly the straightforward example a liberal community such as our own might do well consciously to copy during the coming decade and beyond. The list was a timely reminder why I, too, like Jesus ‘a lot. The real Jesus that is. As the Marginal Mennonite Declaration puts it: ‘The human teacher who moved around in space and time. The Galilean sage who was obsessed with the Commonwealth of God. The wandering wise man who said “Become passersby!”’

So . . .

We, too, like Jesus, need to hang out with sinners.

This has always been necessary but, alas, we are today living through a time in which a deeply problematic moralism is returning to the centre of the public stage which wants to marginalise and exclude those whom it deems sinful and blameworthy in some fashion. In newspapers, on TV and via Social Media all kinds of people are being labelled as irredeemable sinners at the drop of a hat. As the cultural theorist Mark Fisher (1968-2017) wrote in 2013, the “us” and “them” divisions currently being made between those who see themselves as pure and those ‘other sinners is being driven by a priest-like ‘desire to excommunicate and condemn, an academic-pedant’s desire to be the first to be seen to spot a mistake, and a hipster’s desire to be one of the in-crowd’. A key aim in all this is to propagate guilt and encourage its dark consequences. But, as Jesus reminds us, since none of us is without sin and so could never cast the first stone (John 8:1-10) we need always to remember his example by seeking ways to forgive those whom we believe (rightly or wrongly) have sinned against us as we, too, accept the need to be forgiven for our own sins (real or imagined) committed against others. The truth is that any person/community who/which is only prepared to contain and engage with those whom they/it thinks are wholly good and pure is deluded and dangerous. The flawed human condition is such that we sinners (i.e. all of us) need always to find ways to unite so we are able, in love, to begin to find our way through the path of forgiveness to the real possibility of changing our hearts and minds so as to create a better life for all.

We, too, like Jesus, need to upset religious people.

Jesus was constantly irritating those who put themselves up to be the purveyors of a one-and-only eternal, pure and true religion because he knew this was a piece of arrant and dangerous nonsense. As far as he was concerned everything is dissolved into the call to show justice and charity to our neighbour, no matter who they were or what faith they professed.

Religion, like the human cultures from which it springs, is always-already a necessarily multifarious, ad hoc and syncretic thing. It’s a splendidly plural jumble of pluralities and a gay, carefree, and fabulously jumbled up and plural religious movement based on Jesus’ human teaching like the Marginal Mennonites and, I hope our own, has a duty gently to upset all those religious people who cannot see the joy and value of the holy and creative impurity (doctrinal, social and cultural) that is to be found in the ongoing inter-faith encounter.

We, too, like Jesus, need to tell stories that make people think.

In a post-truth age increasingly filled with ‘alternative facts’ this involves truth telling because, as Jesus thought, the truth will make us free (John 8:32). His is a teaching which reminds us of the need always to be bringing a gentle, but relentless religious, political, economic and scientific critique against all those people, powers and structures that are seeking to keep people in the dark about how the world actually is and our possible places within it.

We, too, like Jesus, need to choose unpopular friends.

In our own time age some examples might be the brave children leading the climate strikes, members of environmental groups such as Extinction Rebellion (XR) and Green Peace, legal defenders of democracy and human rights, refugees, migrants and people who voted differently to ourselves. (In other words this means making friends with many of the progressive groups who, shockingly, have been included on an official counter-terrorist information sheet recently released and distributed).

We too, like Jesus, need to be kind, loving and merciful.

Do I need to expand on this, one of the central teachings of Jesus? I don’t think so.

And lastly, but not leastly, we, too, like Jesus, need to take naps on boats.

This, of course, refers explicitly to the story in Mark’s gospel (Mark 4:35-41). This may look to some like a mere piece of humorous fluff at the end of an otherwise serious list. But it’s not. We are living in a culture and time that wants to work all of us (including the planet), but especially the most vulnerable, to the bone and beyond. Consequently, following Jesus’ in the coming years we need to find more and more ways to resist this endless, pathological flailing around our growth obsessed, neoliberal capitalist culture foists upon us and simply stop, think, pray and sleep even in the midst of what may well be for us the most catastrophic of storms.

There are, of course, many other things we might do but this, initial, brief list will suffice to get us going in the right direction.

As we start another decade I recommend the example of the human Jesus to you once again with all the passion I can muster.

I subscribe to a online group called “The Marginal Mennonite Society” — indeed, I consider myself to be a Marginal Mennonite because I find myself very much in agreement with the spirit of their public declaration. For your information and, I hope interest and enjoyment, we’ll read that in a moment. But, having admitted this affiliation, as a minister on the roll of the General Assembly of Unitarian and Free Christian Churches it seems important to point out why this is neither odd nor in conflict with my formal status as a minster. It is because our own church’s origins in Poland during the sixteenth-century are to be found in exactly the same broad, Radical Reformation, Anabaptist movement that gave birth to the Mennonites — we’re very much brothers and sisters with them. This is no better illustrated than via a study of the Collegiants who contained various members from anabaptist groups across Europe (including Mennonites and Socinian/Unitarians) and who included among its members Benedict Spinoza.

Anyway, the “The Marginal Mennonite Society” is often posting all kinds of interesting information about remarkable people and groups who have lived and still live the kind of life espoused by the group including, now and then, the odd Unitarian, Free Christian and Universalist. But last week they posted the list you have on your order of service that served as the New Year’s resolutions posted (or at least re-posted) by a bunch of Trappist monks living in the hills of central Kentucky in the Abbey of Gethsemani. Some of you may already know of this Abbey because it’s the one where Thomas Merton spent a number of years. I’ll read out that list after we have heard the Declaration.

READING

Declaration of the Marginal Mennonite Society

We are Marginal Mennonites and we’re not ashamed. We’re marginal because no respectable Mennonite organization would have us. Yet we consider ourselves legitimate heirs to the Anabaptist tradition.

We reject creeds, doctrines, rites, and rituals. Because they’re man-made, created for the purpose of excluding people. Their primary function is to determine who’s in and who’s out.

We are inclusive. There are no dues or fees for membership. The only requirement is the desire to identify as a Marginal Mennonite. If you say you’re a Marginal Mennonite that’s good enough for us.

We see God as Mother as well as Father, a heavenly parent who cares for all her children. (Isaiah 49:15: “Can a woman forget her nursing baby, or show no compassion for the child who came from her womb? Even these may forget, yet I won’t forget you.”)

We like Jesus. A lot. The real Jesus. The human teacher who moved around in space and time. The Galilean sage who was obsessed with the Commonwealth of God. The wandering wise man who said “Become passersby!” (Gospel of Thomas 42).

We believe the Commonwealth of God is a state of being, a state of transformed consciousness, available to everyone. (Luke 17:21: “People won’t be able to say it’s over here or over there. For God’s Commonwealth is inside you and around you now.”)

We are universalists. In our view, everyone who’s ever lived gets a seat at the celestial banquet table. We claim kinship in this belief with Anabaptist leader Hans Denck, Brethren leader Alexander Mack, and Quaker leader Elias Hicks, among many other universalists throughout history.

We oppose the proselytizing of non-Christians. For us, religious diversity is beautiful. It would be a shame if all Buddhists, Hindus, Muslims, Jews, Jains, Pagans, Pastafarians, etc., were converted to Christianity. So we reject evangelistic projects and missionary programs, no matter how well-meaning they claim to be. (Matthew 23:15: “Woe to you hypocrites! You scour land and sea to make a single convert. And when you do, you make that person more a child of Gehenna than you are.”)

We endorse the “Sermon on the Mount.” In particular the sayings identified by modern scholarship as most authentic. Especially the ones on the following themes:

1. Nonviolence (Matthew 5:39-40/Luke 6:29);

2. Generosity (Matthew 5:42a/Luke 6:30);

3. Unconditional love (Matthew 5:44/Luke 6:27-28);

4. Universalism (Matthew 5:45b/Luke 6:35d);

5. Mercy (Matthew 5:48/Luke 6:36);

6. Forgiveness (Matthew 6:14-15/Luke 6:37c/Mark 11:25);

7. Non-attachment to things (Matthew 6:19-21/Luke 12:33-34/Gospel of Thomas 76:3);

8. Freedom from anxiety (Matthew 6:25-30/Luke 12:22-28/Gospel of Thomas 36:1-2);

9. Non-judgment (Matthew 7:3-5/Luke 6:41-42/Gospel of Thomas 26:1-2);

10. Compassion (Matthew 7:9-11/Luke 11:11-13).

We are pacifists, in the tradition of Bayard Rustin, Vincent Harding, Cesar Chavez, Dorothy Day, Peter Maurin, Mahatma Gandhi, Jane Addams, Jeannette Rankin, Leo Tolstoy, Adin Ballou, Lucretia Mott, George Fox, the nonviolent Anabaptists, and of course Jesus.

We are humanists, feminists, and freethinkers. We are gay, carefree, and fabulous. We believe in art, evolution, revolution, relativity, synchronicity, serendipity, the scientific method, and putty tats. We value irreverence, outrageousness, and a strong cup of tea.

We don’t want to take ourselves too seriously. As someone once said: “God is a comedian playing to an audience too afraid to laugh.” For us, hilariousness is next to godliness.

This declaration is not a creed or doctrinal statement. It carries no weight of authority. We are anti-authority. The above “beliefs” are suggestions only. We could be wrong.

The Marginal Mennonite Society was created in February 2011. Declaration last revised Jan. 20, 2017.

MMS Page Administrator: Charlie Kraybill, Bronx, NYC

MMS Page Administrator: Charlie Kraybill, Bronx, NYC

Visit www.facebook.com/marginalmennonitesociety and “like” us.

Charlie Kraybill, MMS Page Administrator.

—o0o—

ADDRESS

A New Year’s (Decade’s) Resolution?—Be more like Jesus—Some lessons for Unitarian & Free Christians from the Marginal Mennonites and some Trappist Monks

|

| L. to R. Me, Russell and Mark in Little Clacton Village Hall in 1982 |

Whilst I never lost my love for Dylan and ‘The Band’, as the music in today’s service will reveal, in my professional career I primarily became known as a jazz-bass player and not a country, blues or rock one. But, contrary to what you might expect, I owe more thanks to Rick Danko for this than I do to Mark Egan.

This was because Egan’s instruction video was more concerned to show off his virtuosity and use of high-level, abstract musical concepts and techniques than actually to teach me anything practical whereas Danko’s video was a straight-forward, homespun attempt to show you exactly what he was playing and offer an encouragement to copy exactly what he was doing.

Anyway, in short, I left Egan’s video very impressed at his playing but, essentially demoralised at how far away from that I was and with very little practical information about I might actually learn to play the things he did. On the other hand I left Danko’s video able to play a dozen new things and with a much better basic grasp about what one needed to do as a bass player and real sense that I could be one.

Before moving on to my main subject today it’s important to see that I eventually became a competent jazz bass player, not thanks to Egan, but thanks to assiduously copying what Danko did. The take-away point to pop in your pockets is that copying someone/something does not, necessarily, mean you end up being mere copies of them or it.

Now I tell you this because in my own teaching in the ministry, although I always try to draw into view all kinds of other religious and philosophical figures, I still centre things upon Jesus — indeed, I still consider myself primarily to be a minister of the Gospel of Jesus. There are two basic reasons for this.

The first is situational in that we are a liberal, free-thinking church tradition that was inspired into existence by the man Jesus of Nazareth and because we, the members of this church, still aim to meet ‘in the spirit of Jesus’ and, in the words of an old Unitarian slogan, we continue to try ‘to practice the religion of Jesus rather than the religion about Jesus.’

The second is personal; I joined this church tradition as an ordinary member and then trained as one of its ministers because I was captivated by the example of Jesus as a child and ever since then, in admittedly very faltering and continually unsuccessful ways, I have continued to try to model a life based on his example. In the light of my words so far, one way of putting this is to say that Jesus is for me the ‘Rick Danko’ of religious and political figures. Jesus showed me what, basically, I needed to do to become a liberal, religious, free-thinking person and the way to achieve this was, in the first instance, simply to try to copy his basic religious and political moves through the world just as I tried to copy Danko’s basic moves across the neck of his bass.

Simple.

There are, of course, other figures I and this church tradition might have copied but the human Jesus (revealed by Radical Enlightenment inspired historical, anthropological, archeological, sociological, scientific and philosophical study) is ours and, as a church community that still expressly meets in his spirit, that’s the basic ‘instruction video’ about how to become religiously and politically liberal people I/we have to offer the world.

What I am talking about here is, of course, pedagogy, that is to say, the methods by which certain knowledge and skills are imparted in any educational context.

When I taught music one of my jobs was to impart knowledge and skills to a student in such a way that they could get going as bass-players regardless of whether they finally end up as country, blues, rock, punk, death-metal, thrash, indie or jazz bass players.

In my role as minister/teacher here one of my jobs is to impart knowledge and skills to people who walk through that door so they can get going as liberal-religious people regardless of whether they finally end up as Buddhists, Jews, Hindus, Muslims, Atheists, Humanists, Religious Naturalists or Christians.

It’s important here to recall the point I made earlier, namely, that copying someone/something does not, necessarily, mean you end up being copies of them or it. So, just as I was lucky to inherit Rick Danko as the basic model for teaching bass-playing, I was lucky to have inherited human Jesus as the basic model for teaching a basic liberal religious way of being in the world.

At this point I can now directly turn to how copying Jesus offers us various ways to proceed through what will clearly be a very difficult and challenging decade and century for us all and the, what is to my mind, wonderful list from the Trappists and posted by the Marginal Mennonite Society.

The list outlines some of the things at least one Trappist monk is planning to copy Jesus doing. As I read them through last week, I thought, you know what, that seems to me to be exactly the straightforward example a liberal community such as our own might do well consciously to copy during the coming decade and beyond. The list was a timely reminder why I, too, like Jesus ‘a lot. The real Jesus that is. As the Marginal Mennonite Declaration puts it: ‘The human teacher who moved around in space and time. The Galilean sage who was obsessed with the Commonwealth of God. The wandering wise man who said “Become passersby!”’

So . . .

We, too, like Jesus, need to hang out with sinners.

This has always been necessary but, alas, we are today living through a time in which a deeply problematic moralism is returning to the centre of the public stage which wants to marginalise and exclude those whom it deems sinful and blameworthy in some fashion. In newspapers, on TV and via Social Media all kinds of people are being labelled as irredeemable sinners at the drop of a hat. As the cultural theorist Mark Fisher (1968-2017) wrote in 2013, the “us” and “them” divisions currently being made between those who see themselves as pure and those ‘other sinners is being driven by a priest-like ‘desire to excommunicate and condemn, an academic-pedant’s desire to be the first to be seen to spot a mistake, and a hipster’s desire to be one of the in-crowd’. A key aim in all this is to propagate guilt and encourage its dark consequences. But, as Jesus reminds us, since none of us is without sin and so could never cast the first stone (John 8:1-10) we need always to remember his example by seeking ways to forgive those whom we believe (rightly or wrongly) have sinned against us as we, too, accept the need to be forgiven for our own sins (real or imagined) committed against others. The truth is that any person/community who/which is only prepared to contain and engage with those whom they/it thinks are wholly good and pure is deluded and dangerous. The flawed human condition is such that we sinners (i.e. all of us) need always to find ways to unite so we are able, in love, to begin to find our way through the path of forgiveness to the real possibility of changing our hearts and minds so as to create a better life for all.

We, too, like Jesus, need to upset religious people.

Jesus was constantly irritating those who put themselves up to be the purveyors of a one-and-only eternal, pure and true religion because he knew this was a piece of arrant and dangerous nonsense. As far as he was concerned everything is dissolved into the call to show justice and charity to our neighbour, no matter who they were or what faith they professed.

Religion, like the human cultures from which it springs, is always-already a necessarily multifarious, ad hoc and syncretic thing. It’s a splendidly plural jumble of pluralities and a gay, carefree, and fabulously jumbled up and plural religious movement based on Jesus’ human teaching like the Marginal Mennonites and, I hope our own, has a duty gently to upset all those religious people who cannot see the joy and value of the holy and creative impurity (doctrinal, social and cultural) that is to be found in the ongoing inter-faith encounter.

We, too, like Jesus, need to tell stories that make people think.

In a post-truth age increasingly filled with ‘alternative facts’ this involves truth telling because, as Jesus thought, the truth will make us free (John 8:32). His is a teaching which reminds us of the need always to be bringing a gentle, but relentless religious, political, economic and scientific critique against all those people, powers and structures that are seeking to keep people in the dark about how the world actually is and our possible places within it.

We, too, like Jesus, need to choose unpopular friends.

In our own time age some examples might be the brave children leading the climate strikes, members of environmental groups such as Extinction Rebellion (XR) and Green Peace, legal defenders of democracy and human rights, refugees, migrants and people who voted differently to ourselves. (In other words this means making friends with many of the progressive groups who, shockingly, have been included on an official counter-terrorist information sheet recently released and distributed).

We too, like Jesus, need to be kind, loving and merciful.

Do I need to expand on this, one of the central teachings of Jesus? I don’t think so.

And lastly, but not leastly, we, too, like Jesus, need to take naps on boats.

This, of course, refers explicitly to the story in Mark’s gospel (Mark 4:35-41). This may look to some like a mere piece of humorous fluff at the end of an otherwise serious list. But it’s not. We are living in a culture and time that wants to work all of us (including the planet), but especially the most vulnerable, to the bone and beyond. Consequently, following Jesus’ in the coming years we need to find more and more ways to resist this endless, pathological flailing around our growth obsessed, neoliberal capitalist culture foists upon us and simply stop, think, pray and sleep even in the midst of what may well be for us the most catastrophic of storms.

There are, of course, many other things we might do but this, initial, brief list will suffice to get us going in the right direction.

As we start another decade I recommend the example of the human Jesus to you once again with all the passion I can muster.

Comments