Zangedo - another look at John the Baptist's call to repentance in the light of Tanabe Hajime's philosophy

For many of us today, the story of John the Baptist may seem utterly irrelevant. But I think his character still speaks very strongly and usefully to us and, to illustrate this, I would like to pick up on two themes from the story of his appearance in the wilderness - a story usually told during the season of Advent - and I do this for some very pressing and practical reasons.

For many of us today, the story of John the Baptist may seem utterly irrelevant. But I think his character still speaks very strongly and usefully to us and, to illustrate this, I would like to pick up on two themes from the story of his appearance in the wilderness - a story usually told during the season of Advent - and I do this for some very pressing and practical reasons.The first is that of wilderness; the second, that of the need to repent (zange - metanoia) and to proclaiming a baptism for the renewal of the forgiveness of sin.

First of all it seems to me vitally important to observe that John the Baptist appears in the wilderness and not in the midst of a city. A city is, after all, a symbol of living within the horizons of our inherited rules and conceptions about what human life and society should be like and even when we rebel against these inherited rules and conceptions we still reveal that we are framed by them in some way. And so we move along already known and named routes to destinations broadly predetermined, either consciously by ourselves in advance or, unconsciously, simply by the necessary limitations imposed on us due to our current levels of insight and knowledge.

However, true wilderness is, by definition, an environment without such rules, routes, names and destinations. For anything truly to be called wilderness it must, in key respects, remain to us radically unknown and unknowable.

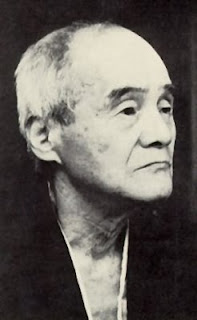

But why would anyone risk walking beyond the ordered city limits out into the wilderness beyond where all the apparent landmarks and securities of civilised life are instantly lost? Well, here we begin to draw close to addressing the matter of repentance because in every individual’s life there come moments when they are forced humbly to admit that they do not know everything, that they are not in control, and that they are in desperate need of change. Most importantly, and disturbingly, it is to acknowledge that they cannot effect the change themselves precisely because of the limitations of their own current state of knowledge and understanding. It is no surprise that this state of mind is often described as like being in a wilderness. It is at this point that I want to take us back to some words of the Japanese philosopher Tanabe Hajime (1885-1962 - a major philosopher of the Kyoto School) which I introduced to you a couple of weeks ago in which he describes his experience of being forced to acknowledge that he did not know all that he needed to know to be a worthy philosopher and that the solution to this distress was not in his power:

'At that moment something astonishing happened. In the midst of my distress I let go and surrendered myself humbly to my own inability. I was suddenly brought to new insight! My penitent confession - metanoiesis (zange) - unexpectedly threw me back on my own interiority and away from things external. There was no longer any question of my teaching and correcting others under the circumstances - I who could not deliver myself to do the correct thing' (quoted in Michael McGhee: Transformations of the Mind - Philosophy as Spiritual Practice CUP 2000, p.11).

Writing about this passage (which comes from Tanabe Hajime's book Philosophy as Metanoetics) you will recall that the British philosopher Colin McGhee emphasised it was not so much that Hajime 'decided that he should do one thing or the other: the point is that he no longer had to make a decision'. As Tanabe Hajime says:

'It is no longer I who pursue philosophy, but rather zange (metanoiesis) that thinks through me. In my practice of metanoesis, it is metanoesis itself that is seeking its own revelation' (ibid. p. 11).

Remember that the crucial point to grasp here is that his new insight comes only after he had absolutely given up - it did not come because of his 'self-power' (jiriki) but only because of an 'Other-power' (tariki). Again Hajime notes:

'This Other-power brings about a conversion in me that heads along a path hitherto unknown to me . . . This is what I am calling metanoetics', the philosophy of Other-power' (ibid. p. 11).

It is at this crucial moment of letting go that necessary space is created for something Other, something new and saving to come over the horizons of our limited thoughts and enter into our frame of reference in a fashion that, on further reflection - enables us to make use of it - i.e. to have our ways of thinking and acting in the world irreversibly changed.

Traditionally, of course, this Other-power (tariki) is called God and although I, personally, am not averse to calling this Other-power (tariki) God the term tariki or Other-power might usefully be employed by those who struggle with traditional concepts of God.

But notice something else too, which is that although the new insight which only comes about in the wilderness is not in one's self-power (jiriki), the Other-power (tariki) which came, could only come in so far are as you had enough self-power (jiriki) truly to admit your inability in the first place! This is another way of saying Other-power and self-power are interdependently related - which, again to use traditional religious language, is to suggest that we not only can meet God in the wilderness but also commingle and become, in some sense, one with God.

But, even though we can rationally explore this process of repentance in the wilderness and encourage ourselves to trust to its ultimate efficacy in itself this is utterly insufficient because it would still be to trust only in our self-power and, therefore, to remain restricted by the limitations of our current ways of thinking.

No! The only way by which we may taste the fruits of this union with Other-power (tariki), with God, is via a real experience of being thrown into wilderness accompanied by a genuine act of repentance in which we truly acknowledge our limitations and failures and then humbly to wait and see what comes. (I am reminded at this point of a well known Zen story about an overful cup).

John the Baptist and his most famous follower, Jesus of Nazareth, were two such people who trusted to this process and in so doing found a new closeness with God and, as a result, discover a new and better way of being in the world which helped them to challenge and modify, in some remarkably effective ways, prevailing ways of thought that, in their own time, were threatening the well-being of society. They needed help badly but they discovered an effective way to access it by entering into a dynamic yin-yang like process in which Other-power (tariki) and self-power (jiriki)were enabled mutually and continuously to inform each other allowing the universal a way to enter the world of particulars, and the particulars to speak eloquently and truthfully of the universal.

Now, you might now be asking what consequences this has for us as liberal religious people today? Well, it actually seems to me to be quite simple although a little bit disturbing to contemplate - especially since we are prone to privilege theorising about faith over actually living it. The plain truth is that in so many areas of our lives, economically, ecologically and spiritually, we are discovering that we are deep in the . . . - well you know what we are deep in and getting deeper into by the year. Many of us are beginning to recognise that the solutions which are being put forward to the problems of our age - including many of our own solutions - are merely disguised reworkings of old and bankrupt paradigms. But of course they are! they cannot possibly change until we begin again to engage in a disciplined process of changing ourselves (zangedo) and so humbly opening ourselves up once again to a real experience of God/Other-power (tariki).

Now I am not quite suggesting that, like some latter day John the Baptist, I take you all down to the river to be baptised, en masse, for the renewal of the forgiveness of sin but I am suggesting that individually and as a community we do need to begin to place at the centre of our religious practice a disciplined but creative and ultimately positive way of repentance or zangedo as Tanabe suggested - a process by which we may slowly clear out old habits and world views and allow something not entirely our own to come into view and transform us. It would, of course, require us to begin to privilege a more meditative and experiential way of being together - i.e. there would be fewer words (mea culpa, mea maxima culpa . . .).

I cannot, of course, tell you what the consequences of engaging in zangedo will be for you or the world because any new vision is, by definition beyond the knowledge of any of us - at least until we have practiced zangedo.

The promise is simple, however, that in doing it we will be opened up to new insights by which we might live a more abundant life. Sure it's risky but finding ways to challenge the prevailing ways of thinking in any society (and our own heads) is always risky but, it seems to me, it is even riskier to carry on in the way we have been.

So my Advent message to you today is simple - no more or less than John the Baptist, Jesus and Tanabe have given in their own times and cultures: "Repent, for a better way of living in the world is at hand."

Comments