Bosons and Barclays, Higgs and Diamond - on the need to look at particular cases

Last week two, apparently unconnected, big news stories - big for our culture that is - came together at the same time. One was the exciting news from CERN (Conseil Européen pour la Recherche Nucléaire) about the discovery of the Higgs boson and the other was increasing realisation amongst us all, to use the words of the Daily Telegraph's Associate Editor, Jeremy Warner, that what occurred in our banking system was "falsification or fraud, not just plain vanilla incompetence, hubris and recklessness."

A situation in which, to deliberately cite another far from radical writer, Charles Moore (the former editor of The Spectator, the Sunday Telegraph and The Daily Telegraph):

"Neither Left, Right nor centre has good new ideas; neither international institutions, nor the European Union, nor independent nation states are functioning as they should. Voters feel so disillusioned and frightened that, in weaker countries, there is a pre-revolutionary situation."

Anyway, although these stories are apparently very different it occurred to me to ask whether there was any kind of meaningful relationship between them and whether, if such a connection existed, whether it might suggest to us, a congregation which values both the natural sciences and a critical, intelligent and inquiring religion, some kind of practical response?

I think the answer is "Yes" and it has something to do with the way we use language. Wittgenstein advised us, and I bring this advice before you every now and then: "Don't think but look!" (PI §66). He meant that when we are asking questions about the meaning of any word (whether "boson" or, as we'll do in a moment words like "reprehensible" or wrong") we must "look and see" the variety of uses to which these words are being put and ensure that our looking and seeing is always done, in the first instance, through particular cases and *not through thought-out generalizations*.

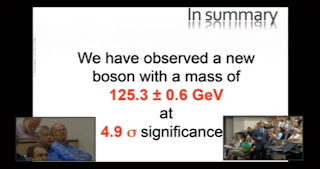

Let's start at CERN. What struck me as I watched both their seminar and press conference was how they took great pains to offer us, the lay public, careful descriptions of the particular cases of bosons that they have seen. Firstly, the word "boson", although it is tied to the particular general theory proposed by people like Peter Higgs, was a placeholder word for something whose likely existence was suggested by countless particular experiments involving other sub-atomic particles. Secondly, the team were very careful to say that, although what they have found in the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) is consistent with what they think a boson should be like, it may or may not prove to be the Higgs boson of the Standard model. For that to be confirmed they require more data and interpretation and so, well, we'd have to wait. In connection with this what also struck me was how Rolf Heuer, the Director General of CERN, began the whole affair by saying: "As a layman I would say: I think we have it. You agree?" This opened up the possibility for a meaningful dialogue about the differences of meaning about in what consists "scientific discovery" that is in use in expert and lay circles. He helped us see that there is a difference in what is meant when an educated "layman" says, "I think we have it [i.e. the Higgs boson]", and what the key particle physicists in the project such as James Incandela, Sergio Bertolucci and Fabiola Gianotti mean when they say "I think we have it". Anyway by constantly tying the word "boson" to particular cases they were able to aim for, and I think achieve, a certain kind of clarity which included, I must add, clarity about what they knew they didn't know (known unknowns) and that, as they continued in their studies, they were highly likely to find some unknown unknowns. Additionally their careful use of language was clearly able to help them to see and articulate how they might meaningfully "go on" in the coming months and years. In short, we saw how their use of language is helping them continue to live well the form of life that is expressed by them as particle physicists.

Here I'd like you to hold on to the idea of a "form of life" and, before we go on it's worth acknowledging David Kishik's wise reminder: "Never look for meaning in isolation but only in the context of a life" (Wittgenstein's Form of Life, Continuum, 2012 p. 55).

Although in any individual human life they can and do overlap, the form of life that we see expressed in the language of the particle physicist is not the same as the form of life we are trying to express in our ethical language. This latter language is not being used to speak clearly to each other about the nature of things in the universe but to try to speak clearly to each other about how we are to live an ethical life (in an ethically informed "world") amongst all the things of the universe.

In both forms of life - the scientific and the ethical - clarity can be reached but, and this cannot be stressed enough, it is a very different clarity that can be achieved in each case. We must not think that we can simply read across to the ethical the kind of clarity we can obtain in the sciences - and here we really do need to "be cured of our craving for generality" (Wittgenstein, Blue and Brown Books, p. 17). What it is to use the word "boson" with clarity in scientific circles is to key the word to repeatable particular cases so that, in the end, we can say what a boson is. But words like "wrong" and "reprehensible" are not tied to particular, repeatable natural objects in the world. Rather they are, as we know, changing, culturally relative concepts related to human life with all its propensity for constant change.

Now I pick up on these two words ("wrong" and "reprehensible") today because they were used many times by Bob Diamond, the former chief executive of Barclays Plc, during his appearance before the Treasury Select Committee (ten times in the case of "reprehensible" and dozens of times in the case of "wrong"). The full transcript is a available here.

When we see someone like Bob Diamond using these words to describe a business which, by looking at other cases, we are beginning to see has developed a culture that didn't think falsification or fraud was either reprehensible or wrong we may begin to doubt that our ethical language still works. We might be tempted to despair.

But let's go back to where I started when I reminded you of the need not to think but look and that we should abandon all explanatory generalization and ensure that our seeing must always be done through particular cases and not through thought our generalizations.

The problem is not with the words "reprehensible" or "wrong" the problem only arises when we don't look properly to see how these words are being used and for what effect. Bob Diamond and his many neo-liberal buddies are gambling that we'll just hear these words, jump to their generalized meanings, and believe what they say, believe that they do think what they have done (and are still doing?) is wrong and reprehensible. But we must resist this temptation and LOOK!

There are three ways by which we might remind ourselves about how to gain clarity here.

The first is the latin phrase "cui bono" meaning "as a benefit to whom?" The Roman orator and statesman Marcus Tullius Cicero attributed the expression to the Roman consul and censor Lucius Cassius Longinus Ravilla:

"The famous Lucius Cassius, whom the Roman people used to regard as a very honest and wise judge, was in the habit of asking, time and again, 'To whose benefit?'" (Pro Roscio Amerino, section 84).

The second is Lenin’s question of "Who, whom?" which the Cambridge political philosopher Raymond Geuss expands to say: "Who does what to whom and for whose benefit? ("Philosophy and Real Politics" p.25).

The third is related to Jesus' teaching about fruits:

"Beware of false prophets, who come to you in sheep's clothing but inwardly are ravenous wolves. You will know them by their fruits. Are grapes gathered from thorns, or figs from thistles? So, every sound tree bears good fruit, but the bad tree bears evil fruit. A sound tree cannot bear evil fruit, nor can a bad tree bear good fruit. Every tree that does not bear good fruit is cut down and thrown into the fire. Thus you will know them by their fruits. Not every one who says to me, Lord, Lord, shall enter the kingdom of heaven, but he who does the will of my Father who is in heaven" (Matthew 7:15-21).

The important point to see here is that the clear meaning of words such as "wrong" and "reprehensible" can never be achieved in the (potentially) stable once and for all fashion that we might achieve with the word "boson" - clarity can only be found by us constantly looking, seeing, testing, asking, and checking with particular cases of the words' use. This is a never ending ethical requirement because our human situation (cultural, political, religious whatever) is always changing. But, as someone once wisely noted, just because I can never accurately state in a once and for all, fixed fashion where the river bed is (it's always being moved about by the flow of water) that does not mean that I cannot walk on the river bed! The river bed may be always shifting but it's always there and I can always walk on it.

The clarity we can achieve by this constant testing of words through particular ethical cases is not merely to see where we might stand but to actually to stand where we stand - not on a theoretical river bed but an actual river bed.

Bob Diamond is gambling that intelligent people like us, who know intimately that our ethical language is, like a river bed, always in flux, will not be confident enough to challenge them strongly. But, as I hope I have been able to illustrate (poorly I know), in truth we are on firm (enough) ground to say: "Actually, Mr Diamond, after looking at your actions and those of your associates and after asking cui bono, who/whom and about your fruits in these particular cases, we feel confident in saying you are rumbled and we can see that despite what you say you didn't think what you were doing was either wrong or reprehensible."

Once we can articulate this kind of charge clearly and with equanimity (after all we don't want here mere knee-jerk witch-hunts starting) there is a chance that the rule of law can take over and make reasoned judgement. If we don't succeed in bringing people like Bob Diamond to justice through the power of words - i.e. through a democracy actually working - then it is only a matter of time before the pre-revolutionary situation elsewhere in Europe mentioned by Charles Moore will make itself felt on these shores. Countries who lose the power of words will not only face violent insurrection but will also loose the creative ability (culturally and financially) to do the kind of wonderful. peaceful co-operative work we saw bear such joyous fruit at CERN this week.

Don't think. Look!

Comments