Sappho’s time-scissored work—A new-materialist meditation for Valentine’s Day

|

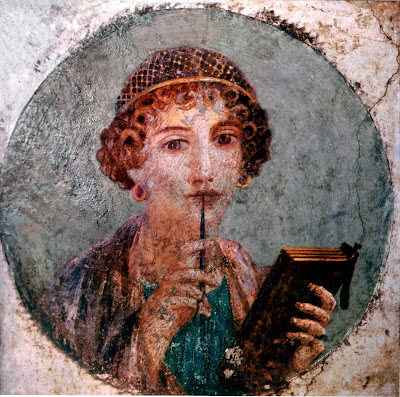

| A portrait of a woman on a fresco in Pompeii & thought to represent Sappho |

You can hear a recorded podcast of the following piece by clicking this link

I begin this podcast for Valentine’s Day by reading two fragmentary love poems written by the Greek poet Sappho (c. 630 BCE – c. 570 BCE). Throughout antiquity she was held to have been one of the greatest lyric poets and, according to Plato even, perhaps, the “Tenth Muse” herself. Both these fragmentary poems were translated by Willis Barnstone.

Afroditi and Desire

It is not easy for us to equal

the goddess

in beauty of form Adonis

desire

and

Afroditi

poured nectar from

a gold pitcher

with hands Persuasion

the Geraistion shrine

lovers

of no one

I shall enter desire

Return, Gongyla

A deed

your lovely face

if not, winter

and no pain

I bid you, Abanthis,

take up the lyre

and sing of Gongyla as again desire

floats around you

the beautiful. When you saw her dress

it excited you. I'm happy.

The Kypros-born once

blamed me

for praying

this word:

I want

—o0o—

Sappho’s time-scissored work—A new-materialist meditation for Valentine’s Day

Valentine’s Day is a day which, since the late fourteenth- and early fifteenth-century, and to the delight of florists, restauranteurs, sparkling-wine, card and chocolate manufacturers everywhere, has become ever more indelibly associated in the public imagination with romantic love. However, despite the day’s current pervasiveness in our culture its origins are extremely obscure. For a while some scholars thought that the day’s roots might be found in an attempt to Christianise the pagan fertility festival of Lupercalia which was celebrated in ancient Rome between 13th and 15th February but, despite the attractiveness of this idea, no real evidence to support this has ever been found. As to St Valentine himself the situation is hardly any better and it remains unclear whether he is to be identified as one saint or is a conflation of two saints of the same name.

But, today, what we do know for sure is that time has cut-up the day’s sources into all kinds of fragments which, over the centuries, have slowly been woven and rewoven together in many complex and utterly contingent, ad hoc (‘to this’) ways. As it is celebrated today, like all our ancient festivals such as Christmas and Easter, St Valentine’s Day is a rich, sometimes beautiful, sometimes grotesque weave of incomplete and endlessly recycling and transforming fragments. In short, it remains a day full of actual and potential meanings — and, in this sense, it is incredibly meaning-full — but it is a day within which we can find no single abiding, stable, simple, essential, complete, central meaning.

For many people this is tantamount to saying that, in truth, a festival such as Valentine’s Day is deeply meaning-less. The thought silently in play here is that true meaning, that which is truly meaning-full, can only be found in something that is, from the beginning and in its unchanging essence, something through-designed, wholly-planned, coherent, complete and in order. However, following the lead of the contemporary Cambridge political philosopher, Raymond Geuss, it has long seemed to me that the world in which we live ‘does not on the whole conform to the patterns, which we think it would be good for it to instantiate. There is a discrepancy between how we perceive the world to be and how we think it would be good for it to be’.

Indeed, as we, through the natural and social sciences, have continued to explore the question of how our world is and our place in it we have found, again and again, that ours is a world which seems characterised, ‘all the way down’, by movement, instability, insecurity, indeterminacy and uncertainty. This means that whatever meaning we do find in the world it is dependent upon, not some underlying stable, independent grid-like structure against which everything can (in principle if not always in practice) always be accurately measured but, instead meaning is dependent upon a reality that is characterised by constant, creative motion. As the Roman poet Lucretius once pithily observed, ‘omnia migrant’ (DRN 5.830), everything moves.

Anyway, with all the foregoing thoughts in my mind, as we headed towards our first locked-down Valentine’s Day I couldn’t but help recall the strange story about how many of the fragments of the sensuous and lyrical love poems of Sappho came to survive into our own time and which continue to inspire and intrigue us some two-thousand-five-hundred years after her death.

As with St Valentine (or the two St Valentines), very little is known about Sappho’s life but, as you heard earlier, what we do know is that her poetry was admired throughout antiquity and was included in the later Greek’s definitive list of lyric poets. Alas, despite her fame, and like so many other ancient authors, nearly all of her poetry has been lost to us and of the more than five hundred poems that she wrote, only two complete poems and about two thousand lines which fit into intelligible fragments have survived into our own day.

Although a few fragments survived in Greece itself, in 1879 in the Egyptian oasis of Fayum in the Nile valley, a great deal of new material was discovered. Now, as you might expect, in Egypt, Sappho’s poetry was written on papyri and papyrus was also the material used to make the papier-mâché with which they wrapped their iconic mummies. When the archeologists working on this site came carefully to unwrap these mummies, to their amazement and delight, they discovered that Sappho’s poetry (along with the work of other ancient authors) had provided much of the raw material. As one of Sappho’s modern translators, Willis Barnstone, puts it, by cutting the papyri upon which the poems had been written into thin strips:

‘The mummy makers of Egypt transformed much of Sappho into columns of words, syllables, or single letters, and so made her poems look, at least typographically, like Apollinaire’s or e. e. cummings’ shaped poems. The miserable state of many of the texts has produced surprising qualities. So many words and phrases are elliptically connected in a montage structure that chance destruction has delivered pieces of strophes that breathe experimental verse. Her time-scissored work is not quite language poetry, but a more joyful cousin of the eternal avant-garde, which is always and ever new. So Sappho is ancient and, for a hundred reasons, modern’ (Sweetbitter Love by Sappho, trans. Willis Barnstone, Shambhala, 2006, p. xxix).

But can a great poet, as Sappho undoubtedly was, still be considered great when her work is, from one point of view so mangled? I think the answer is not only “Yes”, but, in certain respects, this mangling process may have helped her texts become greater. Now how on earth might that be the case?

Well, in relation to the greatness of texts and their possible meanings, you may remember something I have occasionally brought before you for consideration, something that was suggested by the contemporary philosopher Iain Thomson:

‘. . . what makes the great texts ‘great’ is not that they continually offer the same ‘eternal truths’ for each generation to discover but, rather, that they remain deep enough — meaning-full enough — to continue to generate new readings, even revolutionary re-readings which radically reorient the sense of the work that previously guided us’ (Figure/Ground Communication interview).

What I’d like us to think about here is that the greatness of Sappho’s texts, or perhaps it is better to say that the second greatness of Sappho’s texts, is dependent, not on their completeness, but on their very incompleteness, on their fragmentary nature, and that this greatness — their meaning-full-ness — is something that is made possible precisely because of a creative, material reality in which ‘omnia migrant’, everything is always-already moving.

And when you come to think about it isn’t all of human love and life itself just like this too? We know in our heart of hearts that we can never completely know either ourselves or another person. This is because we are all ourselves always-already made up of moving, shifting, contingent, entangled fragments of memory constantly being woven, unwoven and rewoven intra-actively together to create all kinds of new meanings and re-orientations. In other words we are not so much ‘be-ings’ as ‘always-be-come-ings’ and this is only possible because of a creative, material reality in which, thank the ever moving heavens, ‘omnia migrant’, everything moves.

And even at the moment of death, when a life might be said to be as finished and complete as it can be, this same life’s story can still only ever be known incompletely by those of us who remain. At the death of a loved one we all carefully try to gather up the fragments that remain so that nothing is lost because we know that these fragments, like Sappho’s words, can always go on to gift our present and future imaginations with new insights, orientations, stories and poems and, indeed, whole new, meaning-full worlds of possibility.

Anyway, for what it’s worth, it strikes me that one lesson we might take from celebrating St Valentine’s day with these dynamic, kinetic thoughts in play is that we need not be frightened by the fragmentary, ever-moving nature of ourselves, our stories, our poems, or of reality itself, because it is precisely thanks to this endless, time-scissoring movement that we are always being gifted with the freedom to be tomorrow what we are not today and so have the chance to give and receive love again and again until, one day, we ourselves are woven back into the creative, ever-moving stuff of life.

Drawing on Lucretius it was this insight that allowed the English poet, A. E. Housman, to write his own touching love poem of sorts and with it I end this meditation for St Valentine’s Day. It is poem no. XXXII of ‘A Shropshire Lad’:

From far, from eve and morning

And yon twelve-winded sky,

The stuff of life to knit me

Blew hither: here am I.

Now—for a breath I tarry

Nor yet disperse apart—

Take my hand quick and tell me,

What have you in your heart.

Speak now, and I will answer;

How shall I help you, say;

Ere to the wind’s twelve quarters

I take my endless way.

—o0o—

If you would like to join a conversation about this or any other podcast then please note our next Wednesday Evening Zoom meeting will take place on 24th February at 19.30 GMT. The link will be published on this blog and in the notes to the podcast for that week.

Comments

I think I would like some 'cut up' Shelly (printed on recycled paper).. made into a nice patchwork frock for me ..before my body is placed in Barton burial ground with daisy chains.. for me to pass onto my next incarnation..