Where is the life in the place in which others are putting us?—A call confidently to express a Free Religion

|

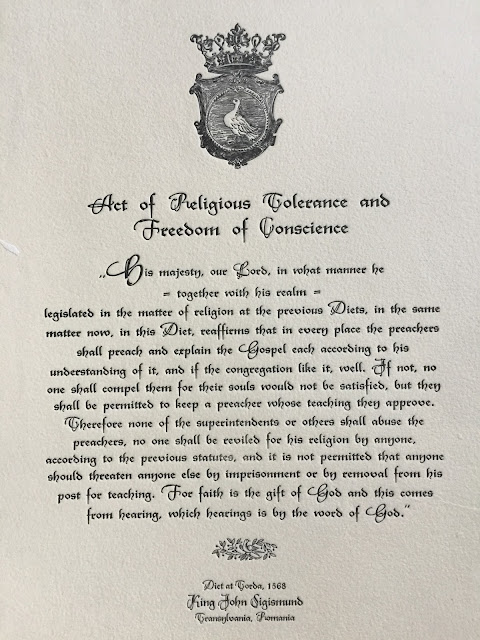

| The copy of the Edict of Torda that I brought to the ecumenical meeting I mention below |

As some of you will be aware, over the course of the last three years I’ve begun exploring in more and more depth the possibilities that might exist for any community that is able, not only merely to talk about Free Religion, but which also actually provides some way to express it through all its various meetings. Our current service of mindful meditation is one actual example of explicit Free Religion and I have quiet hopes that, in the future, we here in Cambridge will be able to create additional expressions of it.

By Free Religion I mean something like that expressed by the important Japanese twentieth-century liberal, minister of religion and teacher, Shin’ichirō Imaoka (1881-1988), who said:

“Free Religion is not a new religion which conflicts with Christianity, Buddhism, or any of the other established religions. Nor is it trying to unite all the established religions. It maintains that no established religion has a monopoly on truth, and that any established religion can become Free Religion if it is humble and anxious to learn truths which are proclaimed by others. The essence of Free Religion is the unification of pure religion and complete freedom, or to put it another way, Free Religion does not lie in doctrines or in rituals but in the manifestation of creative and universal human nature. Accordingly, Free Religion extends to such worldly affairs as politics, economy and science, etc., if they are manifestations of genuine human nature. In other words, they are unorganized religions” (Selected Writings on Free Religion and Other Subjects, p. 79)

Now, the reason for this shift in my own religious focus is because during the course of my twenty-three years of ministry with Cambridge Unitarian Church it’s become ever harder to continue to work, or network with all too many Christian communities. Although in the early 2000s the Cambridge Unitarian Church had a seat on the Centre of Cambridge Churches Forum — indeed I was its moderator one year — as the Christian churches as a whole have continued to shrink in size, the tendency to define themselves narrowly and doctrinally has only increased. Here in Cambridge this first became startlingly obvious to me in about 2013 when the Forum decided to become part of the Churches Together in Britain and Ireland and to change its constitution accordingly. This decision brought into play a doctrinal, Trinitarian statement of faith which actively, and quite deliberately, excludes Unitarians. The local group kindly put into it’s own constitution a clause just for us which allowed a non-creedal church with a long-standing involvement in the Cambridge ecumenical scene to remain a member but, thanks to the dissolving of this group during the COVID-19 lockdowns, any new Churches Together group will assuredly be founded with a constitution that excludes us.

And, before I come to the positive question with which I want to leave you today, here’s one more important and telling example of how we have been actively excluded from Christian circles.

In a service for the Week of Prayer for Christian Unity held in the the chapel of Michaelhouse in 2014, a little ceremony was devised by a small group of us from the Forum where each member church placed on a table in the middle of the chapel something important to their own tradtion. So, for example, the Anglicans brought a Book of Common Prayer and the United Reformed Church brought their “Basis of Union”, and so on through the Methodists, Baptists, Roman Catholics, Russian Orthodox and us, the Unitarians. Following this moment of sharing, the preacher — on this occasion a Roman Catholic priest who was acting as the Roman Catholic Diocesan Ecumenical Officer — was then to deliver a sermon that was to reference each of the gifts in turn and celebrate them. Now, given that this was an ecumenical service about church unity, I brought to the common table a copy of the Edict of Torda from 1568, the first Act of Religious Toleration in Europe that was enacted by a decree of John Sigismund (1540–1571), the Unitarian King of Hungary. The final and, to some people, famous paragraph contains these words:

“[I]n every place the preachers shall preach and explain the Gospel each according to his understanding of it, and if the congregation like it, well. If not, no one shall compel them for their souls would not be satisfied, but they shall be permitted to keep a preacher whose teaching they approve. Therefore none of the superintendents of others shall abuse the preachers, no one shall be reviled for his religion by anyone . . . and it is not permitted that anyone should threaten anyone else by imprisonment or by removal from his post for teaching. For faith is the gift of God and this comes from hearing, which hearing is by the word of God.”

Anyway, the preacher began to preach, speaking about each of the various churches’ gifts in turn except, of course, ours, which was passed over in complete and utter silence. It was one of the most quietly depressing moments in my ministry and it pretty much marked the beginning of the end of my efforts to be involved in any pro-active way in the Christian ecumenical scene here in Cambridge, although a second key event occured the following year, about which you can read here.

Of course I, or perhaps another member of the congregation, could attempt to get back regularly involved in the ecumenical scene but, be assured, if you do try and succeed even in a small way (as I did at a meeting in the Cambridge Guildall only last week between churches in Cambridge, the City Council and the Police), the churches themselves will continue to keep you very firmly at arms length and often in a place beyond the(ir) pale.

For many years this has been for me a source of great sadness, regret and, yes, depression but, recently, a Unitarian colleague who was responding to my story and who has experienced similar things in their own work, asked me and a couple of other Unitarian ministers this powerful and, I think, potentially transformative question:

“Where is the life in the place in which others are putting us?”

As I have already indicated, I think the answer to my colleague’s question lies in our own community firstly, finding ways to accept, confidently and publicly, the truth that most Christian churches have put us in a place that lies completely outside their ecumenical family (pale) and that, therefore, we no longer belong to the Christian church; and, secondly, and again confidently and publicly, to embrace the ideal of Free Religion — an ideal that I think can be shown, not only to have been shared by Jesus in his own time and context, but also by many other religious heroes and examplars from other religious and philosophical tradtions throughout history. Were we to be able to embrace this identity as a free religious community we could then properly turn our attention to finding ways to use our buildings and other resources to provide the city of Cambridge with a genuinely open place for people to meet and freely to converse and envision a much better and inclusive religious and philosophical vision for the future than the exclusionary and sectarian ones currently offered by too many advocates of traditional religion in general, and by the Christian ecumenical scene in particular.

So, today, may I be permitted to ask all of you, as I continue to ask myself:

“Where is the life in the place in which others are putting us?”

Comments