Is the earlier always the purer, the better? Strawberry Fields Forever and Tolstoy's Gospel in Brief

No MP3 this week folks. Sorry about that but the nature of the address, with it's many musical illustrations, made it impossible to record in a meaningful way.

****

In 1931 Wittgenstein wrote in his notebook,

Tolstoy: the meaning (importance) of something lies in its being something everyone can understand. That is both true and false. What makes the object hard to understand - if it's significant, important - is not that you have to be instructed in abstruse matters in order to understand it, but the antithesis between understanding the object and what most people *want* to see. Because of this precisely what is most obvious may be what is most difficult to understand. It is not a difficulty for the intellect but one for the will that has to be overcome (MS 112 221: 22.11.1931, CV 25e).

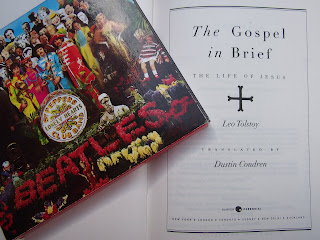

The reason I cite this passage today is because, as I mentioned last week, I am at the moment re-reading Tolstoy's 'Gospel in Brief' (GiB) in a new, and what I think is a wonderful translation by Dustin Condren.

This book was profoundly influential upon my own thinking and religious practice because it remains the only interpretation of Jesus' teachings that I have been able to follow and live with a clean heart and conscience. I responded to it's message directly because, to pick up on Wittgenstein's note, it seemed to me to reveal 'something everyone can understand', something which required no knowledge of abstruse matters. Indeed, since I first got hold of a copy back in the mid-nineties I have always carried it with me in my bag and I turn to it again and again and, to be honest, I find it speaks to me more authoritatively and meaningfully than do the four canonical Gospels themselves.

Now, given that Tolstoy's GiB seems to me to reveal something important that 'everyone can understand', and which that requires no knowledge of abstruse matters, you might legitimately be wondering why I have so infrequently spoken of this book's message preferring, instead, to speak more often of Wittgenstein, a man whose philosophy, it has to be admitted, is something not everyone can understand and which does seem to require knowledge of abstruse matters.

Well, here's why and - though it is not the main point of this address - I hope what follows will simultaneously encourage you both to take a look at the GiB and also to make you a little more kindly disposed to Wittgenstein.

As I said, when I first read the GiB, I found a book whose religious message resonated profoundly with me. In the immediate act of reading, its message shone for me as obvious, true and spiritually enlivening. But a short time after every reading - especially whenever I considered using the text as a central example in one of my own addresses - a nagging doubt would re-enter my mind that this was 'just an interpretation'. What I really *wanted* - i.e. what my culture told me I *wanted* and using the word *want* in the way Wittgenstein does - was to be able to dispense with, not only Tolstoy's interpretation but also the interpretation of the Gospel writers themselves and, with the aid of modern Biblical scholarship, I wanted somehow to get back to an underlying truth - the 'real' Jesus of history. I (and my culture) has long imagined that to stand in front of him - if it were possible - I would assuredly be in the presence of actual truth. But, whenever I take time to add up all the knowledge and insights brought by Biblical scholarship about the historical Jesus I have to admit that what I find is, though often intriguing and suggestive, as a whole message, roughly drawn, ill-formed, crudely expressed and, in some cases, irrelevant and even mistaken. I find in this still developing historical picture nothing that offers me a faith actually to live by.

But in most of our Western European Christian traditions this feeling that earlier is better, more truthful, less corrupt is incredibly strong indeed - not least of all because of the divine status accorded to Jesus (wrongly from the perspective of the tradition in which this church stands - though I think there are a lot of good ways to use 'trinitarian' language - here's a link to an address I wrote on the subject) . So strong is this that, even when I felt to the core of my being that in the GiB I was encountering a religious orientation to the world that was obvious and true - the very thing which I was looking for - because I, which is also to say my cultural inheritance, *wanted* to see something else the obviousness of the GiB became for me, as Wittgenstein says, 'what is most difficult to understand.'

Consequently, for the whole of my eleven year long ministry I have been embarrassed - profoundly ashamed even - to admit in public that I find the GiB to be for me a more persuasive, attractive and helpful indication of how to orientate myself in the world than the four canonical Gospels.

I have to say that my intellect has no difficulty here at all and this is why Wittgenstein's work is so important because he helps me, us, to see that the difficulty is not an intellectual one by what our culture *wants* or *wills* us to see. In this case in matters of religion related to Jesus it is to *want* to see that the earlier is always better, truer, purer. To overcome this is a problem of the *will* and it is a matter of great personal concern to me that I overcome this if I am ever to going to respond honestly to what seems really obvious to me so I can, in turn, be honest with you and, perhaps now and then, even a little easier and obvious to understand.

But for this to occur I need to be sure that you, too, don't get also caught up with what our culture tells us we *want* to see. Without overcoming this, that which is obvious and something everyone can understand, will remain incredibly hard for any of us to see. But how to show this? Well, as you will have realised, I'm going to try to do it through The Beatles.

On the 17th February 1967 the Beatles released the single 'Strawberry Fields Forever' a song inspired by John Lennon's childhood memories of playing in the garden of a Salvation Army house named "Strawberry Field" near his home. It represents a defining moment in pop music because it opened up possibilities for it which showed, as the critic Ian MacDonald said that, 'given sufficient invention, [it] could result in unprecedented sound-images' and offer us 'moods and textures' which formally had only 'been the province of classical music.' MacDonald goes on to say that:

'Heard for what it is - a sort of technologically evolved folk music - Strawberry Fields Forever shows expression of a high order. While there are countless contemporary composers capable of music vastly more sophisticated in form and technique, few if any are capable of displaying feeling and fantasy so direct, spontaneous, and original' (Ian MacDonald, Revolution in the Head, Fourth Estate, 1995, p. 175).

But we won't start with this single as it was released. Instead, let's go back to the song's inception. We can do this because we are fortunate that there exist recordings of almost every stage of the song's genesis, from Lennon's original demos to the final version you'll hear at the end.

Lennon began to piece the song together on his acoustic guitar whilst in Spain filming 'How I Won The War' during September 1966. MacDonald suggests that Lennon:

' . . . seems to have lost and rediscovered his artistic voice, passing through an interim phase of creative inarticulacy reflected in the halting, childlike quality of his lyric. The music, too, shows Lennon at his most somnambulistic, moving uncertainly through thoughts and tones like a momentarily blinded man feeling for something familiar' (ibid p. 173).

Here's a short medley of the demos John made when he finally got back to the UK. In it you will hear all the things MacDonald pointed out - not least of all that Lennon was like a 'momentarily blinded man feeling for something familiar'.

This 'feeling for something familiar' continued in the studio. For the first three days the Beatles worked on a band version. Here's 'Take 1'.

By 'Take 7' they had got down a fine version - described by one of their close associates as 'magnificent'. Any other group would have been happy to leave it here.

As good as this version was Lennon wasn't happy, and after leaving the track for a week he approached their producer and musical collaborator, George Martin, and got him to agree to start again only this time with an arrangement using trumpets and cellos over a very dense rhythm track. But Lennon still wasn't satisfied and another week later he told George Martin that he wanted to splice the first part of the original version onto the second part of the new one. Now, because the two takes were recorded in different keys and at different speeds George Martin 'venture[d] mildly that this was impossible' but Lennon insisted. MacDonald continues:

'By sheer fluke, it happened that the difference in tempi between the two takes was in nearly exact ratio to the difference in their keys. By varispeeding the two takes to approximately the same tempo, Martin and his engineer Geoff Emerick pulled off one of the most effective edits in pop, detectable only in a change of ambience (at 1:00). This swoop from the airiness of the first chorus/verse into something more shadowy, serious, and urgent was what Lennon had been groping for all along, yet ultimately it had to be achieved through controlled accident' (ibid p. 174).

In a moment we'll hear the song as it went into pop music history but firstly I'll conclude with the basic religious/spiritual message of this address.

I take this story of the creation of Strawberry Fields Forever as being analogous to my experience of the GiB. The GiB feels to me somewhat like the final version of Strawberry Fields Forever, Lennon's demos are the 'historical Jesus' and the first takes are the Gospels as we have inherited them in the New Testament.

In the same way that I do not dismiss the earlier versions of Strawberry Fields Forever, I most certainly do not dismiss the sketchily drawn historical figure we discover through Biblical scholarship and nor do I dismiss the four Gospels - they are themselves clearly 'magnificent' - just like take 7. But, again and again, for me they are not quite on the money and in them I encounter Jesus and those first authors very much as people 'moving uncertainly through thoughts and tones like momentarily blinded men feeling for something familiar' just like Lennon. Many of the key truths and insights are present but they just don't quite come together for me in a truly satisfying and inspiring way. For me, however, in his GiB Tolstoy succeeds by fearlessly taking those initial truths and insights by foregrounding some and amplifying them in importance, whilst placing other elements in a less obvious view, by editing out some things and adding other, entirely new elements and, lastly, by trusting as did Lennon to the extraordinary possibilities that are thrown up by chance.

But, I realise that the GiB won't be to everyone's liking here. So it is important to extend my illustration to suggest that I think we, as a whole community, need to see ourselves as being something like the Gospel in Brief (and, therefore, something like the master take of Strawberry Fields Forever). We need to make of ourselves a Gospel, respecting the historical Jesus we can only vaguely glimpse and certainly enjoying the 'magnificent' take on his teaching and example that are the canonical Gospels, but not satisfied until we can make them into a new and wholly unexpected 'song' - that expresses satisfyingly and persuasively for us in our own age and time the indefinable truth that we have only partially glimpsed in the historical Jesus and the Gospels.

But whatever else you take away from this address please remain wary, very wary, of believing that in religion earlier versions of our Christian story are assuredly purer and better than ones told closer to our own day. It's what our culture wills us to *want* but it is precisely this which continues to stop us from seeing the obvious - namely that there is always a new, fuller and richer song waiting for us to sing.

Comments

The attitude that older is better in matters of religion perhaps stems from the idea that revelation is sealed - that the old prophets had access to transcendent experience and newer ones do not.

But Unitarians have always affirmed that revelation is not sealed - that fresh insights may break forth from the numinous.

One thing I would like add to your point is that although Unitarians may be alert to the fact that 'revelation is not sealed' (something I certainly agree with) it can blind them to the fact that it is only by keeping in close living and creative relationship with earlier traditions that we are freed to structure meaningfully the new 'revelations'. Depending on new revelation alone encourages, as James Luther Adams saw, only confusion - perhaps at times this confusion will prove interesting but it remains confusion nonetheless.

In my opinion the continuing problem with much modern Unitarianism (in the UK and USA) is that it just doesn't seem to understand this and this is why it is rapidly disappearing. The trick is, surely, really to be something (for us here in Cambridge it is to be clearly to be upholders of the liberal Christian tradition) but to be it in a way that not only continually allows for new revelation, the new song to be sung, but for it also to be heard by us and others as 'counting for something' - i.e. capable of structuring corporate meaning and worth - of bringing sense and order rather than, at best, 'interesting confusion'.

Readers might be interested in following this link to a piece by David E. Bumbaugh called 'The unfulfilled dream - We neglected the Universalist challenge of restating our core convictions in contemporary terms'

The unfulfilled dream - We neglected the Universalist challenge of restating our core convictions in contemporary terms

What is any liberal Christian religion?

I am confused.

Is anything definitive?

Thanks for your question. In brief, no, I don't think there is anything definitive, neither in terms of metaphysical beliefs nor practice - nor do I think there can be.

What there can be, however, is what we might call a certain liberal Christian *continuity* whenever a person and/or community models themselves on the person of Jesus in a certain way. I've explored this thought before in an address entitled 'No image, no passion'.

This way of approaching the liberal Christian tradition (I prefer to use the word 'tradition' to 'religion') doesn't result in the creation of any definitive beliefs or practices but it does give us a meaningful continuity with earlier generations of Christians and also helps us to structure meaning and worth in the present in such a way that we are not closed down to the new ways the world shows up (shines) for us today (a world certainly very different from Jesus' own and even that of fifty years ago).

You might also be interested in reading the following piece by John B. Cobb called Liberal Christianity at the Crossroads.