Steep and lofty cliffs and a dumb-struck priest - Second Sunday in Advent

MP3

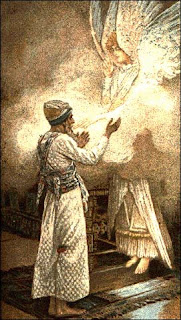

MP3One of the stories that is told at this time of year has always puzzled me, primarily because I never knew what to do with it. It's the story we heard earlier of the priest Zechariah being struck dumb in the temple by the angel Gabriel (Luke 1:5–24; 59–64).

At least as I was taught the story it was primarily to be understood as an example of piqued, divine power - Zechariah doesn't believe God's messenger so, taking umbrage, God uses his power to teach the poor man a lesson for his lack of trust by shutting him up until he realises the error of his ways. It's an unattractive reading and is one that I've long left aside as unhelpful.

I've come to feel that a more fruitful way of entering this story can be found when you take the position that its author had noticed something resonate in their own imagination which, in turn, helped them notice something important about what it is to be a human being in the world. In penning his story Luke was, perhaps then, simply trying to help his readers notice the same thing, i.e. this resonance. We may suggest that Luke attempted this by giving this resonance a semblance of objective reality - in this case the story of Zechariah being struck dumb in the temple. The apparently literal descriptive elements of Luke's story are, though a necessary part of its telling (after all it's what makes it *this* story and not another) these literal descriptive elements are not precisely the *point* of the story.

Some of you will recall that I've tried to illustrate this thought before by using as an example some lines from the beginning of William Wordsworth's poem 'Tintern Abbey'. I'm very indebted to the British philosopher Michael McGhee for this helpful insight.

. . . once again

do I behold these steep and lofty cliffs

that on a wild secluded scene impress

thoughts of a more deep seclusion.

The important thing to see is that Wordsworth is not writing a poem the point of which is a mere description of the so-called real physical facts of 'steep and lofty cliffs' in a 'secluded scene' but, instead, offering us a poem in which these things somehow correspond to, or resonate with, a state of mind he is experiencing - those 'thoughts of a more deep seclusion'. Wordsworth's hope is that, if he is successful, then his readers' minds and imaginations will also experience this resonance and there will be a correspondence between author, reader and, of course, the steep and lofty cliff in a secluded scene. The consequence of this is a possibility that there can arise amongst us a new collective reality which helps us continue to encounter the ever-changing and unfolding world as meaningful and intelligible.

Now it may be the case that Luke's story had some basis in actual historical facts that could be described in fashion similar to steep and lofty cliffs - i.e. once upon a time, a priest somewhere did tarry in a temple and come out dumb and later, on regaining his voice, speak of an angel of the Lord and give his child an unexpected name. You can clearly describe all these things but if this description - this semblance of reality - is all you see then this would be to miss the point which is to feel the resonances that it set up in the author's imagination and which he wanted to share with his readers.

Alas, it is has always been far too easy to lose this sense of semblance and to allow our thinking and pondering about these kinds of stories and all kinds of other aesthetic ideas and images to degenerate into a form of naive theological realism.

When we do succumb to this temptation we can end up with so pretty problematic literalistic readings and I'm sure I do not need to rehearse a list of them here.

Before we move on we must be clear about one important thing. There is, however, no way we can ever know for sure that what might resonate in our imaginations today is the same thing that resonated in the imagination of the author - whether it be Wordsworth or Luke. It wasn't possible in any assured way amongst their contemporaries but to us, two centuries or two millennia later, it should be clear that both of these authors' worlds are radically different from our own. The physical things they describe - steep and lofty cliffs, seclusion, a ruined abbey, a temple, a priest, an angel - were all woven together in quite different, networks of belonging and understanding about the nature of the world than that we have today.

In short I think it is pointless to worry about whether the resonances we may feel today about either the poem or Luke's story are the same as those felt by Wordsworth, Luke and their contemporaries.

At this point we'll leave Wordsworth and concentrate upon this particular Advent story of Luke's and ask is there something to be seen in this story which sets up a resonance in us such that we might be taught a lesson useful to our own age and circumstances?

I think the answer is 'Yes' and that it's related to the fact that we seem to be in an age and culture which feels like it is on the cusp in many many ways.

The present financial and political crisis is one looming example of this - we feel that we are on the cusp of desperately needing new financial and political structures to order our society. Another example is the beginnings of a feeling that we are on the cusp of a needing a new scientific paradigm to order our understanding of the physical world. Lastly, there has been what is for many the surprising return of religion to the sphere of public discourse and it's happened in a way that makes us all feel we are in desperate need for a paradigm shift in our personal and corporate understandings of religious faith and praxis.

Feeling "on the cusp" makes many (perhaps most) of us somewhat anxious. We'd either like the old ways to remain and return to a certain stability or, if we are a little more adventurous, we are impatient to get things over with and rush into the new paradigm, the new world-view, way or style of being now.

I think most of us have a sense that many of the old world-views really aren't cutting it and that in important ways they are broken and need to be revisited and re-imagined. But the perennial truth of the matter is that first glimpses of every new way or style of being in the world always appears in our own present time, within our present world-views. This means that we are forced to try to talk about new political, financial, scientific and religious paradigms using the languages of the old because that's all we have.

From time to time, however, at those moments when we intimate most strongly what the new paradigm might be like we find to our frustration, and perhaps horror, that we run out of all adequate words. We find ourselves reduced either to silence or to its noisy, verbal equivalence which is to begin to talk in strange and incomprehensible tongues as we try to force our old language almost to breaking point.

We have to try to do if we are to help those who have no glimpse of the new paradigm glimpse it themselves so as to gain a sense of why we feel it is so important - we have no choice but to do this with language they, and we, already know. We find that we are only slowly unwound from within our tradition/language into a new understanding. (Jonathan Lear explores a similar thought in his book Radical Hope about the Crow Indian tribe.)

Now, if we turn to look at old Zechariah is not his situation something like our own and does it not resonate with us and our present condition?

There he is, a senior figure in his field and completely embedded in a particular world of ancient and well-tried practices but in a time of great ferment and change. It seems not unreasonable to imagine that the circumstances in his world forced him to spend time thinking through the problems and issues of his day and, like us, was finding things to be a little rickety, a little "on the cusp". Alone in the sanctuary of the Lord he would certainly have the space and quiet to think deeply on these matters and to imagine a different way and style of being in the world. We may imagine, too, that it is likely that in such a place of contemplation - a kind of laboratory - that he could have experienced a powerful vision of a new way or style of belonging - given by Luke in his story the form of the angel Gabriel. That vision suddenly showed up the world to him in a new light. Seeing such a vision so suddenly is it any wonder that he was rendered speechless? His old words and old practices just couldn't do the new vision justice.

All he could do, in his silence or perhaps at other times in some garbled attempts at coherent speech, was bear public witness to the fact that the world could, given the right conditions, begin to show up differently to others too. But, as is appropriate to the theme of Advent, any new collective adoption of a new way or style of being requires some kind of patient waiting.

Nine months later his wife Elizabeth finally bears a child. In the Christian narrative this child is, of course, not himself the new way but just part of the unwinding into it. At the child's circumcision family and friends - living firmly in the old paradigm - want to call the child Zechariah after its father. After all Zechariah and his role represented the old ways at their best so why should his child not be given such a venerable name? But no, Elizabeth, who as the child's mother has been an intimate part of the emergence into the world of this new paradigm, knows the new name, it is to be "John". All present turn to Zechariah, they give him something to write upon and he writes "His name is John." Immediately his lips are freed, somehow, everyone present is given something of the new way of talking about the world that was impossible but a short time before.

It seems to me that today we are so like Zechariah in so many ways. The resonance is, I think, palpable.

We see before us a timely reminder that change into a new style of being, a new language, is always a process of slow unwinding that proceeds one word at a time. Like a child a new language, a new style of being, is never given to us fully formed, it grows and, like all growing things, we have to be patient not only for its birth but also about its growth and development.

It doesn't matter, as I've already said, that we cannot know whether this is the resonance Luke felt and wanted to pass on to us. We only need be thankful that the universe - which includes texts like this - seems to be able to gift us an infinite number of ways of speaking and being. As our opening hymn said in traditional language: "The Lord hath yet more light and truth to break forth from his word."

Comments