Just like Jericho, "let these walls come tumbling down" — After the Future, a Post-Futurist Manifesto — some thoughts following the Jeremy Clarkson fracas

|

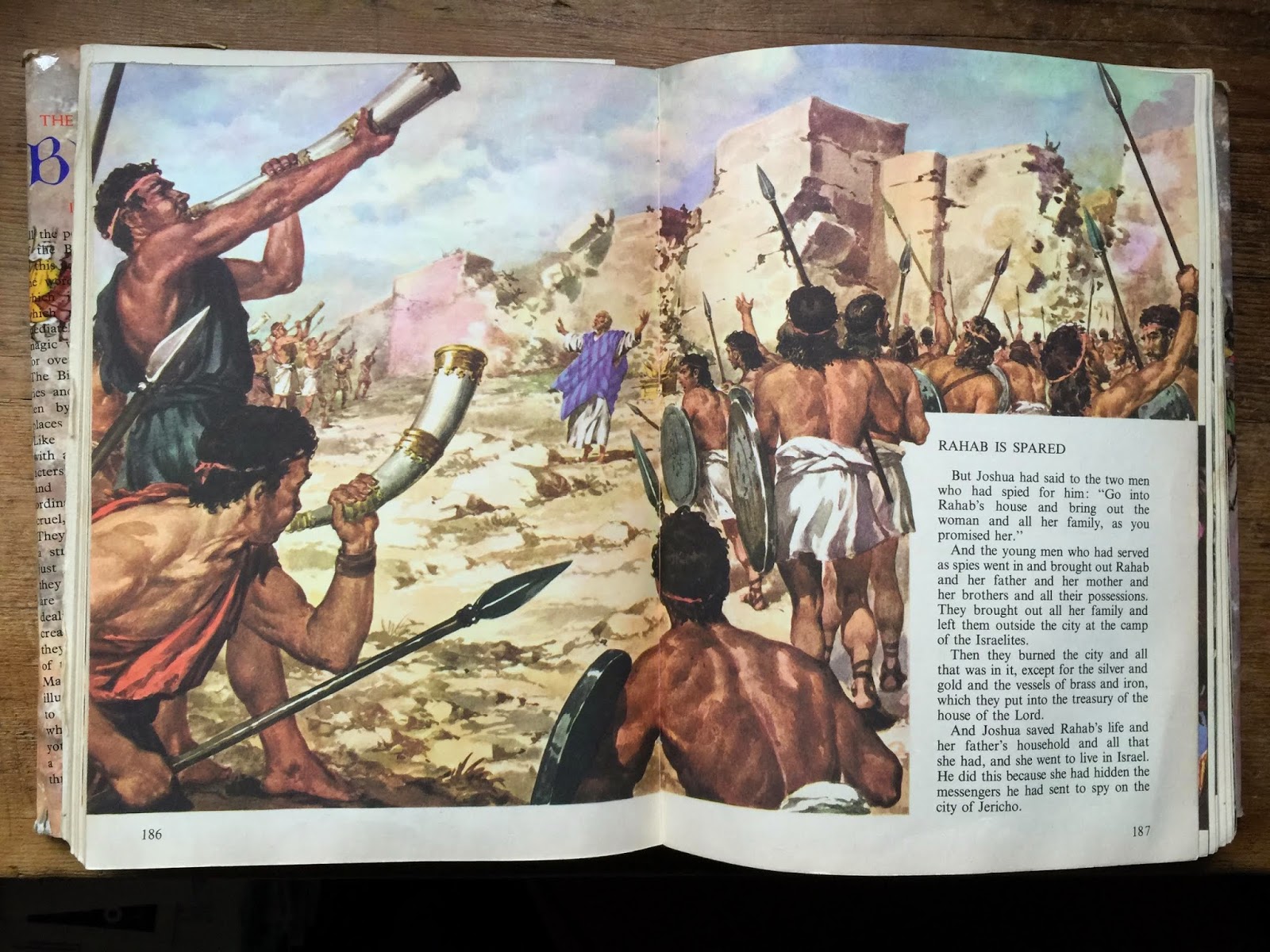

| The Walls of Jericho from my Children's Bible |

It’s fair to say, I think, that it’s a very strange story indeed and one which, as Matthew Henry says rather dryly in his famous commentary, certainly describes an “uncommon method of besieging the city”. Uncommon indeed — unique, I think. But if the siege method described was uncommon it has to be said that the general Christian interpretation of the story serves simply to turn it into just another way merely to persuade people of God’s supreme power and, as Henry says, that “all the victories were [and are] from him”.

Whenever I was offered this interpretation by my Sunday School teachers or ministers, it always seemed to me to destroy its wonder and oddness and left me with nothing other than a rather boring religious, so-called “fact” about God’s power, the truth of which, even by the age of ten, I was already beginning seriously to doubt.

If that’s all the story could teach me then I could safely forget it . . . and, as a teaching story, forget it I have. That was until this week when two things came together which allowed a rather more interesting, amenable and useful interpretation of the story to emerge. What those two things were we’ll come to in the address, but before we come to them let's remind ourselves of the very odd story about the walls of Jericho:

The first thing that occurred during the week was the surprising number of people (five) who came up to me specifically to ask about the Italian philosopher, Franco “Bifo” Berardi, after I mentioned his book “The Uprising: Poetry and Finance” during last week’s service. Later on, two other people in email correspondence did the same and said they were getting hold of the book. This is, I assure you, a very unusual occurrence —none, one or, tops, two is the usual figure.

The second thing that occurred during the week was the continuing brouhaha over Jeremy Clarkson’s suspension as presenter of “Top Gear”. “Top Gear” is the TV show that, more than any other, has glamourised and pandered to the cult of the very fast, powerful and very expensive car. Today, I don’t want in any shape or form to get involved in the rights and wrongs of the whole Clarkson debacle but, instead, wish simply to note that the sheer number of people signing a petition to have him reinstated (nearing a million as I write) and the four million drop in viewers for the replacement programme, clearly reveals there remains in our culture an obsession with both speed and power. It is not at all insignificant to my theme today that the petition was delivered to the BBC in a tank (an iconic symbol of violent power) and that the driver of the tank was a character called "The Stig" who, as always, was dressed as a Formula 1 racing driver (an iconic symbol of speed).

It is all this that brings me back to Bifo. One of the things he has written, to which I’m going to introduce you to today, is a “Post-Futurist Manifesto” (found in his book, "After the Future") . But before we can consider that you need to know a little something about the Futurist movement and its associated manifesto written in 1908 by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti.

Futurism (Italian: Futurismo) was an artistic and social movement that originated in Italy in the early 20th century and which rejected the past and emphasised and glorified speed, technology, youth, violence, war and objects such as the car, the aeroplane and the industrial city. Marinetti brought all these things together in his Manifesto and he produced a document which, as will quickly become evident, was to prove highly congenial to the nascent Italian Fascist movement. The manifesto also gave birth to a twin, Russian Futurism, many of whose ideas were were borrowed by those who created totalitarian Soviet Communism. So here is the Manifesto. Do be warned, it is a thoroughly nasty little document:

Manifesto of Futurism (Translated by R. W. Flint)

1. We intend to sing the love of danger, the habit of energy and fearlessness.

2. Courage, audacity, and revolt will be essential elements of our poetry.

3. Up to now literature has exalted a pensive immobility, ecstasy, and sleep. We intend to exalt aggressive action, a feverish insomnia, the racer’s stride, the mortal leap, the punch and the slap.

4. We affirm that the world’s magnificence has been enriched by a new beauty: the beauty of speed. A racing car whose hood is adorned with great pipes, like serpents of explosive breath — a roaring car that seems to ride on grapeshot is more beautiful than the Victory of Samothrace.

5. We want to hymn the man at the wheel, who hurls the lance of his spirit across the Earth, along the circle of its orbit.

6. The poet must spend himself with ardour, splendour, and generosity, to swell the enthusiastic fervour of the primordial elements.

7. Except in struggle, there is no more beauty. No work without an aggressive character can be a masterpiece. Poetry must be conceived as a violent attack on unknown forces, to reduce and prostrate them before man.

8. We stand on the last promontory of the centuries!… Why should we look back, when what we want is to break down the mysterious doors of the Impossible? Time and Space died yesterday. We already live in the absolute, because we have created eternal, omnipresent speed.

9. We will glorify war — the world’s only hygiene — militarism, beautiful ideas worth dying for, and scorn for woman.

10. We will destroy the museums, libraries, academies of every kind, will fight moralism, feminism, every opportunistic or utilitarian cowardice.

11. We will sing of great crowds excited by work, by pleasure, and by riot; we will sing of the multicoloured, polyphonic tides of revolution in the modern capitals; we will sing of the vibrant nightly fervour of arsenals and shipyards blazing with violent electric moons; greedy railway stations that devour smoke-plumed serpents; factories hung on clouds by the crooked lines of their smoke; bridges that stride the rivers like giant gymnasts, flashing in the sun with a glitter of knives; adventurous steamers that sniff the horizon; deep-chested locomotives whose wheels paw the tracks like the hooves of enormous steel horses bridled by tubing; and the sleek flight of planes whose propellers chatter in the wind like banners and seem to cheer like an enthusiastic crowd.

It is profoundly disturbing to see how this manifesto so accurately predicted the way our European culture would go during the twentieth-century. To be sure, the fact that, here at least, we find much of what it contains abhorrent is a sign that we may have matured just a little since then, but the additional fact that the document as a whole still seems to speak accurately of so many of our own culture’s current attitudes and ways of behaving should be, I think, a cause of great worry. Notice, too, how so many of these ideas also resonate with those currently trumpeted by a modern extremist group like ISIS.

And you know what? I don’t like the world it promotes at all. In fact it is this kind of world-view — whether expressed in our own or another culture — that brings me closest to expressing my own anger about it in aggressive and violent ways. Fortunately (in my opinion) I’m so shaped by Jesus’ calls to non-violent direct action (and the calls of people like Tolstoy) that I have some real hope I will never be tempted myself down the route of violence but I know, first hand, that similar feelings to my own are abroad amongst many people like me who are increasingly aware of the desperate need to find ways meaningfully and effectively to protest and campaign against war, violence, speed, hatred of women, patriotism, militarism, nationalism and the wilful destruction and exploitation of earth’s resources and our museums, libraries, academies of every kind.

Alas, I think there can be no doubt that violent angry protest against these things will begin to occur more frequently in the next few decades and that it will be challenged by an equal and opposite violent reaction. We caught a minor glimpse of this process unfolding just this week with the protests outside the new European Central Bank HQ in Frankfurt.

But I’m completely with Berardi in believing that the “organisation of violent actions . . . would not be smart, as violence is a pathological demonstration of impotence when power is protected by armies of professional killers” (The Uprising, p. 132).

If Berardi and I are right in holding this opinion what are we to do if we wish to protest effectively and non-violently against the ideals found in Futurism? Here we turn finally to the story of the Walls of Jericho because Berardi thinks we need to be communicating to the world an important truth, namely:

“. . . that a collective mantra chanted by millions of people will tear down the walls of Jericho much better than a pickaxe or a bomb” (The Uprising, p. 133).

Now that is an uncommon method of bringing change! But, in the current political and cultural situation when so many of us are acutely feeling our lack of power this approach rings so true with me. In this sentence of Bifo’s I think we can see a glimpse of how in the coming decades we might, perhaps, best be playing out our own radical church tradition. I'd venture to suggest that we need to find ways to contribute to the explicit creation of such a mantra that might poetically, and non-violently, be powerful enough to pull down the walls that divide us and so begin to transform the world in gentle and peaceful ways.

But what might such a mantra look like? Is there any model we can begin to work with and perhaps begin to disseminate? Well, the answer is “yes” for Berardi has offered up to us a first-take in his own “Post-Futurist Manifesto” published in February 2009, a manifesto that deliberately recasts the horrific Futurist manifesto published a hundred-years previously.

With it I’ll finish — let it stand today as a kind of “Amen” to my address for you to think about in your own time and ways. I won’t interpret it in anyway but just let it’s poetic force strike you (or not) as it will. Following the manifesto I have put a link to a short twenty minute interview with Bifo about this subject which you may wish to see.

So now, imagine me walking with millions of others round the walls of our many unfit for purpose institutions ("Jerichos" all) and saying together, again and again, this mantra/manifesto for a different world . . .

”Post-Futurist Manifesto” (creatively read in English by Erik Empson and Arianna Bove)

1. We want to sing of the danger of love, the daily creation of a sweet energy that is never dispersed.

2. The essential elements of our poetry will be irony, tenderness and rebellion.

3. Ideology and advertising have exalted the permanent mobilisation of the productive and nervous energies of humankind towards profit and war. We want to exalt tenderness, sleep and ecstasy, the frugality of needs and the pleasure of the senses.

4. We declare that the splendour of the world has been enriched by a new beauty: the beauty of autonomy. Each to her own rhythm; nobody must be constrained to march on a uniform pace. Cars have lost their allure of rarity and above all they can no longer perform the task they were conceived for: speed has slowed down. Cars are immobile like stupid slumbering tortoises in the city traffic. Only slowness is fast.

5. We want to sing of the men and the women who caress one another to know one another and the world better.

6. The poet must expend herself with warmth and prodigality to increase the power of collective intelligence and reduce the time of wage labour.

7. Beauty exists only in autonomy. No work that fails to express the intelligence of the possible can be a masterpiece. Poetry is a bridge cast over the abyss of nothingness to allow the sharing of different imaginations and to free singularities.

8. We are on the extreme promontory of the centuries… We must look behind to remember the abyss of violence and horror that military aggressiveness and nationalist ignorance is capable of conjuring up at any moment in time. We have lived in the stagnant time of religion for too long. Omnipresent and eternal speed is already behind us, in the Internet, so we can forget its syncopated rhymes and find our singular rhythm.

9. We want to ridicule the idiots who spread the discourse of war: the fanatics of competition, the fanatics of the bearded gods who incite massacres, the fanatics terrorised by the disarming femininity blossoming in all of us.

10. We demand that art turns into a life-changing force. We seek to abolish the separation between poetry and mass communication, to reclaim the power of media from the merchants and return it to the poets and the sages.

11. We will sing of the great crowds who can finally free themselves from the slavery of wage labour and through solidarity revolt against exploitation. We will sing of the infinite web of knowledge and invention, the immaterial technology that frees us from physical hardship. We will sing of the rebellious cognitariat who is in touch with her own body. We will sing to the infinity of the present and abandon the illusion of a future.

Comments