Following in the footsteps of Hypatia—some personal reflections

|

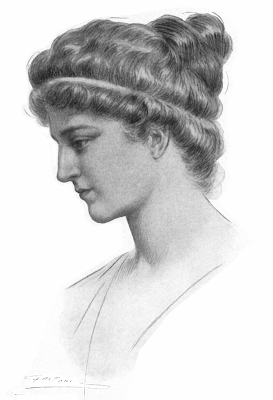

| "Hypatia" by Jules Maurice Gaspard (1862-1919) |

1) All formal dogmatic religions are fallacious and must never be accepted by self-respecting persons as final.

2) Reserve your right to think, for even to think wrongly is better than not to think at all.

3) Life is an unfoldment, and the further we travel the more truth we can comprehend. To understand the things that are at our door is the best preparation for understanding those that lie beyond.

4) Fables should be taught as fables, myths as myths, and miracles as poetic fancies. To teach superstitions as truths is a most terrible thing. The child mind accepts and believes them, and only through great pain and perhaps tragedy can he be in after years relieved of them.

5) In fact men will fight for a superstition quite as quickly as for a living truth often more so, since a superstition is so intangible you cannot get at it to refute it, but truth is a point of view, and so is changeable.

The portrait of Hypatia that heads this post was by Jules Maurice Gaspard (1862-1919) and was included in Elbert Hubbard's book “Little Journeys to the Homes of Great Teachers” (New York: Roycrafters, 1908) which is available at archive.org

—o0o—

Although I am myself an active member of the Religious Naturalist Association (I administer their online clergy group) I do subscribe to the newsletter of another religious naturalist group called the Spiritual Naturalist Society which last week contained one of the sayings of Hypatia you heard earlier. I was very struck by her words and followed them up by trying to find out more about her and her remarkable story, the outlines of which you also heard earlier (see links above).

The five sayings I came across attributed to Hypatia struck me as being highly relevant to our own free-religious and free-thinking tradition and so, in today’s address, I’m going to walk through them and make a few, personal comments along the way in the hope that, together, they’ll provoke some helpful thoughts of your own.

1) All formal dogmatic religions are fallacious [i.e. based on a mistaken belief] and must never be accepted by self-respecting persons as final.

This saying certainly speaks directly to the Unitarian tradition’s historical attitude towards religion in general. Over the centuries it’s commitment to rational, critical thought, and thanks to advances made in human knowledge via the natural sciences, has meant it is possible for someone like me to see that what struck my ancient forebears as true (and which, in turn, became the basis for humanity’s formal religions) cannot any no longer strike me as true. One clear consequence of the process has been that it is possible to see all formal, dogmatic religions are, indeed, fallacious and “must never be accepted by self-respecting persons as final.”

This is still something that on occasions I find quite hard to say so boldly because I grew up and came to maturity at the tail-end of a period in British culture in which it was widely thought we could be polite about dogmatic religion because, in the face of the apparently overwhelming evidence continually being stacked-up against it, it would simply wither away and die of its own accord. How wrong we were. As I have got older and been able to see more and more the dangers and dreadful consequences of allowing dogmatic religion to go politely unchallenged, I find I’m increasingly willing to repeat in public, gently but ever more firmly, Hypatia’s ancient words.

Her words also encourage me to continue to try and articulate ways by which we might develop some kind of modern, informal, ad hoc, non-dogmatic, non-final religious practice and to remind me that in my own religion I must constantly be in the business of revising my beliefs about the world. This is, of course, always a risky business because, even as it continually opens up opportunities to discover genuine new truths it also opens me up to the likelihood that I will make mistakes and get things wrong. But, as our Hypatia also said, it is vitally important to

2) Reserve your right to think, for even to think wrongly is better than not to think at all.

This remains as true in our own age as in Hypatia’s. Many representatives of the dogmatic religion — and indeed countless other dogmatic circles — will always be trying their hardest to remove my, and your, right to think. Plus ça change plus c’est la même chose and her words remind me of the ever-present need for free-thinking in human life.

3) Life is an unfoldment, and the further we travel the more truth we can comprehend. To understand the things that are at our door is the best preparation for understanding those that lie beyond.

Understanding life as an unfoldment means that it is possible to speak of the unity of the world in a radically different way to that spoken of by dogmatic monotheism with its commitment to a metaphysical, complete and perfect One, Whole, or Being.

(In passing: You might remember that a few weeks ago I pointed out that instead of using the term "monotheism" it is sometime better to use the term offered up by Peter Soloterdijk, "covenantal singularisation project", which has the benefit of including in its reach secular dogmatic political and social projects.)

I think that a different way of speaking about unity is vital because dogmatic monotheism has, and continues to, encourage people into adopting patterns of thinking and acting which cut violently against the evident creativity and diversity of life and the workings of Nature out of which life has emerged.

The idea of unfoldment connects well with a very Lucretian idea, namely, that although Nature is clearly a sum, it is not a Whole and, as Brooke Holmes puts it when speaking about Lucretius (and Deleuze), Nature is, perhaps, best thought of as being “a structured principle of causality that engineers diversity”, one that is capable of endlessly producing and re-producing difference.

Hypatia seems to me to be correct in suggesting the only way to gain the best possible understanding of such a complicated and diverse world is by travelling out into it, starting from our own doorstep and then step by step unfolding my own life into the wondrous world of difference and diversity all around me.

It was by travelling just such a path that the Unitarian and Universalist tradition began, from as early as the late eighteenth century, to articulate the idea that true unity was not to going to be found in some undifferentiated One, Whole or Being but only in diversity and it was this insight that gave rise to the Unitarian tradition’s common use of phrases like the “interdependent unity of all things” and, these days, I find I share with Gilles Deluze, writing about Lucretius, the strong feeling that

“There is no combination capable of encompassing all the elements of Nature at once, there is no unique world or total universe” (Appendix to "The Logic of Sense" trans. Mark Lester, Athlone Press, 1990, p. 267).

From where I stand it seems that it is precisely this ever unfolding plural quality of Nature that makes it so amazing, beautiful, creative, awesome and mysterious and which also assures me that I have the genuine freedom to be tomorrow what I am not today. As Hypatia says, life is, indeed, an unfoldment.

4) Fables should be taught as fables, myths as myths, and miracles as poetic fantasies. To teach superstitions as truths is a most terrible thing. The child mind accepts and believes them, and only through great pain and perhaps tragedy can he be in after years relieved of them.

These words resonate with my own strong feeling that there is absolutely no need to abandon or suppress the superstitious fables, myths and stories about miracles I inherit from my forebears so long as I am extremely careful not to pass them on to anyone else as truths about the way things are.

Her words words as a scientist and mathematician also remind me, to borrow some lines from Lucretius, that the

“. . . darkness of mind must be dispelled, not by the sun’s light or its rays’ shafts but by careful observation and understanding of inner laws of how nature works” (De Rerum Natura trans. David R. Slavitt, University of California Press, 2008, p. 7).

This is why it is vital that good science and scientists must be welcomed, celebrated and given a central and honoured place in every building and community where people gather to draw continuing inspiration from fables and myths because it is only through the help of the natural sciences that someone like me is given sufficiently powerful and genuinely effective ways to avoid the great pain and tragedy that follows whenever superstition gains the upper hand.

However, in all this it is important to remember that science without the loving friendship and fellowship of poetry is as problematic as poetry without the loving friendship and fellowship of science. By following Hypatia and, particularly Lucretius and keeping poetry and science together, I am enable to see how it is possible to gift people with the fables and myths of our culture but without simultaneously gifting them the dark problems that come when we insist they believe them to be true.

Hypatia’s words serve to remind me that both poetry and science are required if we are to have both a genuinely pleasurable and rational life — as Lucretius says, we need “naturae species ratioque”, both the (poetic) face and (scientific) inner workings of nature (De Rerum Natura, 1.148, 2.61, 3.93, 6.41).

5) In fact men will fight for a superstition quite as quickly as for a living truth - often more so, since a superstition is so intangible you cannot get at it to refute it, but truth is a point of view, and so is changeable.

And, lastly, Hypatia’s words serve to remind me of two further important things.

The first is that in unstable times filled with serious and increasing crises, as our own seems to be, as Lucretius observed:

“. . . people tend to revert under stress to their earlier superstitions and imagine cruel taskmasters, omnipotent beings we wretches ought to fear and appease . . .” (De Rerum Natura trans. David R. Slavitt, University of California Press, 2008, p. 253).

In such unsettled times these kind of fear-inducing superstitious beliefs in god all too easily and quickly become re-attached to dangerous ideas about nationhood, race and religion. It is, of course, the very intangibility of these superstitious beliefs that often makes them so hard to challenge and this is just one more reason for ensuring we form strong and respectful alliances with the natural sciences and have a duty to keep alive the tradition of critical free-thinking.

Anyway Hypatia’s words remind me that I have a duty to try to stop this return to superstition in every way possible.

The second important truth of which this saying reminds me is the etymology of the word “truth”. In Greek the word is “aletheia”, the literal meaning of which is “the state of not being hidden; the state of being evident.” Consequently, in addition to being translated as truth, aletheia can also be translated as “unclosedness”, “unconcealedness” or “disclosure”.

Notice Hypatia speaks about “living truth”. For me, a finite and mortal creature, there is no access to such a thing as capital T truth — or even to knowledge about whether such a capital T truth exists. For every human being truth is something that has to be lived as we journey through life exploring, gathering together unconcealing and disclosing more and more perspectives and viewpoints to gain the best possible all-round picture of reality. Truth for me has to be something always collaborative, multi-perspectival and subject to constant modification and change — and, whenever truth is understood like this it may be said to be a “living truth”. Living truth is, therefore, capable of change and modification whereas the dead, static “truth” of dogmatic religion is not.

In unstable times I can see why such a static dogmatic religious truth can seem attractive to many people but, taken together, Hypatia’s words remind me of the need always to be pushing against any kind of dogmatic "covenantal singularisation project" and resolutely and proudly to stand on the side of a genuinely free-thinking and ever unfolding religious and scientific enquiry so as to lead the most pleasurable imperturbable and reasonable life possible for as many people as possible.

I can do no more today other than highly to recommend Hypatia’s words for your further reflection.

Comments