The Lestrygonians, Cyclopes and angry Poseidon are real and prowling once again through our world — a critical re-reading of Cavafy’s “Ithaca” on the twentieth anniversary of my ministry with the Cambridge Unitarians

|

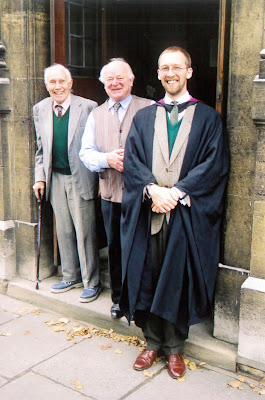

| The last three Cambridge ministers, l. to r. John McLachlan (1967-1976) Frank Walker (1976-2000) Andrew Brown (2000-) |

I quickly recalled (I do not know why) that in my first year here I gave an address which took as its text, C. P. Cavafy’s (once well-known) poem “Ithaca” in Rae Dalven’s translation. The poem’s images are, of course, drawn from Homer’s epic poem “The Odyssey.” Here it is:

—o0o—

Ithaca

C. P. Cavafy (1863-1933), translation by Rae Dalven

When you start on your journey to Ithaca,

then pray that the road is long,

full of adventure, full of knowledge.

Do not fear the Lestrygonians

You will never meet such as these on your path,

if your thoughts remain lofty, if a fine

emotion touches your body and your spirit.

You will never meet the Lestrygonians,

the Cyclopes and the fierce Poseidon,

if you do not carry them within your soul,

if your soul does not raise them up before you.

Then pray that the road is long.

That the summer mornings are many,

that you will enter ports seen for the first time

with such pleasure, with such joy!

Stop at Phoenician markets,

and purchase fine merchandise,

mother-of-pearl and corals, amber and ebony,

and pleasurable perfumes of all kinds,

buy as many pleasurable perfumes as you can;

visit hosts of Egyptian cities,

to learn and learn from those who have knowledge.

Always keep Ithaca fixed in your mind.

To arrive there is your ultimate goal.

But do not hurry the voyage at all.

It is better to let it last for long years;

and even to anchor at the isle when you are old,

rich with all that you have gained on the way,

not expecting that Ithaca will offer you riches.

Ithaca has given you the beautiful voyage.

Without her you would never have taken the road.

But she has nothing more to give you.

And if you find her poor, Ithaca has not defrauded you.

With the great wisdom you have gained, with so much experience,

you must surely have understood by then what Ithacas mean.

—o0o—

|

| My former, idealistic self at a church tea-party in 2000 |

But only a single year into my ministry I recall thinking about whether I should be crossing my fingers behind my back as I wove my naive, liberal, privileged nonsense on that Sunday morning some two decades ago.

|

| With Shirley Fieldhouse at my formal service of induction, Sept. 2000 |

|

| Sharing a story with John McLachlan, minister between 1967-1976 |

For them the Lestrygonians, Cyclopes and angry Poseidon were not only internal, psychological-spiritual menaces (though they were assuredly those as well) but also real, physical presences in their lives. When you are a vulnerable and marginalised person (especially if you are of the “wrong” colour or religion and/or look shabby and dirty) you will assuredly meet many people like the giant, man-eating, rock throwing, Lestrygonians who want to sink your boat and/or kill or drive you away from their land; you will assuredly meet giant, one-eyed Cyclopes who will force you to become a “nobody” (an “outis” who has to hide their true identity in order to survive) and who will lock you up and abuse you for being forced to beg/steal absolutely necessary provisions simply to stay alive; you will, especially if you are a migrant fleeing war and poverty from outside these dark isles, meet the angry god Poseidon in the form of the rough, life-threatening stormy sea across which you have been forced to travel and which is patrolled by boats containing crew, some of whom are assuredly Lestrygonians and Cyclopes. They are people who, on arriving at Ithaca (whether their Ithaca was the UK in general or specifically Cambridge City) are not going to be able to linger luxuriously outside in their “yachts”, wealthy with all they’ve gained on the way, but people desperate to make landfall and to experience just a little of the hoped for riches and opportunities of Ithaca itself. But on landing even that hope is quickly taken from them because Ithaca is, indeed, a poor place and they find they have been fooled, not least of all because it turns out to be another outpost of Lestrygonians and Cyclopes, and one that all too often willingly worships at the altar of the angry god Poseidon.

This latter picture has, alas, only become ever more true during the twenty years of my ministry. My experiences (all shared with Susanna who has been an endless, loving support throughout) have meant that I now cannot read Cavafy’s poem without being quietly (and occasionally, like now, less than quietly) enraged, sickened and offended by it and my own, former, way of interpreting the text. My experiences (minimal though they have been in comparison with those of other, ministerial colleagues) coupled with a careful reading of the Hispanic social-ethicist and theologian Miguel A. de La Torre, the recent resurgence of the Black Lives Matter campaign following the brutal murder of George Floyd, the rapidly increasing climate emergency, the challenge to democratic forms of government and, of course, the COVID-19 event, has hammered home to me (with life-disturbing force) the vital importance of re-reading all my once cherished texts (poetic, library biblical, philosophical, theological) through the eyes of those who have been, and still are being, marginalised by our dominant culture and forcing them to become refugees and migrants (internally and externally).

To borrow and repurpose some words from Marx and Engels’ Communist Manifesto of 1848 (one of my own, cherished, foundational texts that, of course, also needs to be reread in the light of the above) as I arrive at my twentieth anniversary I find that all which I once thought was solid has melted into air, all that I once thought was holy is profaned, and I find that I am at last being properly compelled to face with sober senses, the real conditions of my and other people’s lives, and my relationships with my fellow human beings.

From one perspective the foregoing might be read as the product of a very disappointed man. And that’s true, I neither can nor wish to deny this. But from another perspective I think the foregoing is also, therefore, the product of someone who has, at long last and thankfully, begun to wake up to (and properly intra-act with) how the world actually is, and this fact alone should, I think, be affirmed and embraced by me.

Fortunately, along with the philosopher Simon Critchley (whose work must also now be re-read) I’m a great believer that philosophy doesn’t begin in wonder (as Plato [Theaetetus 155d] and Aristotle [Metaphysics 982b] believed) but in disappointment of at least two major kinds: religious and political. Our culture’s (and my) religious disappointment arose from a loss of faith in the god/s of our forbears and which generated in turn “the problem of what is the meaning of life in the face of nihilism”. Our (and my) political disappointment has come “from the violent world we live in and raises the question of justice in a violently unjust world” (Infinitely Demanding, Verso 2007, pp. 2–3).

From where I am standing today it is precisely this deep disappointment (rather than Cavafy’s shallow wonder) that is helping to reignite my passion and drive towards achieving justice and fairness for all NOW, and that is why I choose to embrace (with huge trepidation and fear) this hugely challenging lesson.

Consequently, although I go away now on a month’s leave, severely chastened and disappointed, I go knowing, thank heavens, two things: 1) that the decks of my rather crappy, unseaworthy (philosophical/theological) boat are a great deal less cluttered with dangerous (and, frankly, useless) ideals than they were even six months ago and, 2) my ability to glimpse the world for what it is really like for most people is, just perhaps, beginning properly to emerge — though I must frankly acknowledge that my vision is still very, very poor thanks to the theological, philosophical, economic and political coma I’ve been in for most of my adult life.

So, I trust that when I return in September I’ll not only be little bit rested but also just a tiny bit more effective in finding new and better ways to join (as an enlisted Private and not an Officer) with those marginalised by our present culture and so help play a modest part in actually bringing about the kind of world Jesus thought was possible — not one founded in privileged luxury on, or at the end, of the journey (in, or moored just offshore, some mythical Ithaca) — but in people’s everyday, modest lives in the here and now. But I realise, for this to even have the faintest chance of occurring, I will be required to play my part in challenging and defeating the very real and very nasty Lestrygonians, Cyclopes and angry and ancient gods of war and violence that are again prowling through our world.

But, as we begin to do this necessary work (which will for a long time offer us all only blood, sweat, toil and tears) let’s not forget our culture’s own role in creating Lestrygonians, Cyclopes and angry and ancient gods of war and violence in the first place. The peace, justice and fairness for which we yearn can only truly come to pass when, as Jesus clearly knew, it finds ways to heal, include and involve those who were once our enemies.

Comments

On the matter of hope - that's now rather complicated for me because, following Miguel A. De La Torre's lead, I think hope (at least as we have traditionally understood it in liberal religion) is a major problem and stumbling block and that we should, in fact, be thinking about embracing hopelessness instead. I have recently tried to explore something of this during Easter when the lockdown was in its early weeks. You can, should you be minded, read that piece at the following link:

For the good of all let’s cancel our subscription to the resurrection—A reflection for the Easter Weekend of 2020

If the ideas that piece contains makes any sense to you then I'd also highly recommend watching De La Torre's recent keynote speech given to a conference of Presbyterians called "Embracing Hopelessness".

Embracing Hopelessness

Naturally, you'd be most welcome at any of the services we may have in the future and I very much look forward to meeting you at some point. I should just note, however, that reopening sometime in September is an aspiration rather than a fixed and firm plan. The challenges of opening are not insignificant for a very small congregation such as our own and, as I know you will be aware, we are far from being through this event and there are likely to be further serious hiccups in everyone's plans for reopening. Please keep an eye on the newsletter page of the church website for updates to our plans. Just so you are aware, because I am currently on annual leave, there won't be an update until I get back to work in the first week of September.

Newsletters

Lastly, I hope that you and yours remain well in the coming weeks.

Every best wish,

Andrew

I will certainly look up those references. I wrote my Masters dissertation a few years ago on the subject of hope so have a particular interest in the word, and how we use it. Margaret Wheatley the writer of "Leadership and the new Science", also wrote more recently about hopelessness.

Warmly

Clare