“A being (l’étant) is a human being and it is as a neighbour that a human being is accessible — as a face.”

|

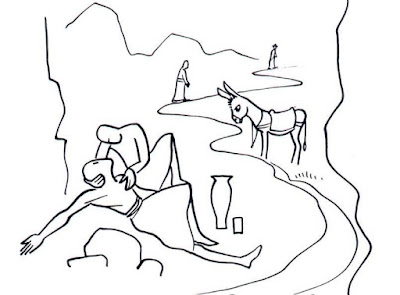

| The Good Samaritan by Annie Vallotton |

Zechariah 7:8-10

The word of the Lord came to Zechariah, saying: “Thus says the Lord of hosts: Render true judgements, show kindness and mercy to one another; do not oppress the widow, the orphan, the alien, or the poor; and do not devise evil in your hearts against one another.”

Deuteronomy 10:17-19

For the Lord your God is God of gods and Lord of lords, the great God, mighty and awesome, who is not partial and takes no bribe, who executes justice for the orphan and the widow, and who loves the strangers, providing them with food and clothing. You shall also love the stranger, for you were strangers in the land of Egypt.

Luke 10: 25-37—The story of the Good Samaritan

The Principles and Purposes (1985): The covenant of the member congregations of the Unitarian Universalist Association, as adopted in 1985 and modified in 1995.

ADDRESS

“A being (l’étant) is a human being and it is as a neighbour that a human being is accessible — as a face.”

Last week I gave an address arguing that an individual cannot initially get properly going as a liberal religious person without having before them an initial personal model or prototype to imitate. I argued that without this there is no image and no passion and therefore no effective way for a person to get an actual grip on what being a religious liberal is nor enough motivation to put in the very difficult work required to attain, and then maintain and further develop this particular way of being religious in the world. Historically speaking, since the Enlightenment, our corporate model has been one or other of the historical Jesus’ presented by, for example, Thomas Jefferson, Leo Tolstoy, Stephen Mitchell, Don Cupitt (our neighbour over the road at Emmanuel College) or the associated various Jesus Seminar authors such as Thomas Sheehan or John Dominic Crossan. In the local context I should point out that the Cambridge Unitarian church community was founded in 1904 following a series of lectures the previous year by J. Estlin Carpenter on the subject of "The historical Jesus and the theological Christ" (published in 1911) and our first minister, J. Cyril Flower published a book called "The Parables of Jesus applied to Modern Life" in 1920 and penned some words which still grace our church's entrance: "Our religious thinking is related to the teaching of Jesus and its application in the modern world."

Last week in the conversation immediately following the address a few people pushed back against this suggestion in favour of adopting from the outset multiple possible models or, alternatively, a set of general purposes and principles because this they felt this was a pluralist approach better suited to liberal religion as a whole. Well, in the light of the comments made last week, I’ve had time carefully to think again about this and I find that I still think I’m right and that multiple models and principles and purposes are too broad an image which is insufficiently concrete enough to serve as a focus for attainment. Naturally, my thinking this doesn’t make me right and I acknowledge that it may well have to be the case that, on this matter, we’ll simply have to agree to differ.

Having offered this caveat I consider the question to be important enough to take another pass at the subject to see if I can persuade you of what I think is the vital and indispensable need for having, at a primordial level, a grounded, personal model or prototype to imitate and not a set of possible models or general principles and purposes such as, for example, the one adopted in 1985 (and revised in 1995) by our North American sister church, the Unitarian Universalist Association.

I bring them up because these principles and purposes have become increasingly influential here in the UK and many of our churches would prefer to centre themselves upon them rather than upon the kind of kind of statement centred in some way upon the model of Jesus our churches used to make. So, for example here’s our own church covenant based upon that written in 1880 by the Rev. Charles Gordon Ames, minister of the Spring Garden Unitarian Society in Philadelphia:

“In the love of truth and the spirit of Jesus the members of this congregation unite for the worship of God and the service of humankind.”

I can see clearly why a move away from our kind of statement and towards a set of principles and purposes would be very attractive and I assure you that I’m not immune myself from such a feeling. Our covenant can feel very old fashioned when it is brought side by side with modern, liberal and progressive principles and purposes.

But what concerns me, deeply concerns me and drives me to give this address today, is the evidence on the ground — here in the UK, across Europe and in the USA — that the appeal to liberal, progressive purposes and principles (no matter how attractive and valuable they are) have not provided the required ethical motivation to persuade enough people fully to come to live a liberal religious life so as to assure the continued flourishing of both liberal religion and, it has to be said, liberal democracy. Let’s not avoid the disturbing fact that liberal religious congregations everywhere continue to be in a state of what looks like terminal decline. Remember that in the UK the current official national membership is only 3095 and, in the USA it is only 199,850.

Following the British philosopher, Simon Critchley, my reading of things is that we are allowing illiberal and reactionary people and ideologies increasingly to gain the upper hand over us because we are continuing to think that, primordially speaking, our liberal and progressive salvation lies in finding better ways to promote abstract purposes and principles to which we can rationally appeal and to which we — and we believe others — can, under the right conditions, rationally assent.

But over the seventeen years of my ministry I have slowly come to think that this way of thinking is to see the world upside-down. But as I say this please be careful to hear what I am saying. I am not saying that principles and purposes and the use of reason are somehow useless and meaningless — far from it — but what I am saying as loudly and strongly as possible is that, ethically speaking, they are second-order things, things born out of something much more primordial. To help show you what I think this more primordial something is I want to draw today on an insight of the extremely important French philosopher of Lithuanian Jewish descent, Emmanuel Levinas (1906-1995).

For Levinas, as Simon Critchley observes, “the core of ethical experience is . . . the demand of a Faktum, but it is not a Kantian fact of reason so much as what we might call ‘a fact of the other.’” (Simon Critchley, "Infinitely Demanding", Verso Press, 2007, p. 56)

In other words a grounded ethics of commitment is not primordially rooted in a set of higher principles and purposes to which one must rationally assent and cooly accept (a vertical, hierarchical relationship) but in a visceral, white-hot and sometimes traumatic encounter with the fact of the other, our neighbour (a horizontal, democratic relationship). Critchley notes that:

“The ethical relation begins when I experience being placed in question by the face of the other, an experience that happens both when I respond generously to what Levinas, recalling the Hebrew Bible, calls ‘the widow, the orphan, the stranger’, but also when I pass them by on the street, silently wishing they were somehow invisible and wincing internally at my callousness” (Simon Critchley, "Infinitely Demanding", Verso Press, 2007, p. 56).

Notice, too, that what is beginning to be suggested here is that ethics is situated in the face-to-face encounter and that morality only follows on later, where morality is some kind of agreed upon (or imposed) set of rules, principles and purposes. Another way of putting this is to say that everything valuable that we might find in a given set of purposes and principles only emerges from (and is rooted in) the infinite ethical demand experienced in a face to face encounter.

Here’s how Levinas himself puts it:

“A being as such (and not as incarnation as universal being) can only be in a relation where we speak to this being. A being (l’étant) is a human being and it is as a neighbour that a human being is accessible — as a face” (“Is Ontology Fundamental?” in “Basic Philosophical Writings”, Indiana University Press, 1996, p. 8).

[NB: This insight is given extra power when you combine it with another, one highly congenial to Unitarians expressed by a member of the Jesus Seminar, Thomas Sheehan. Sheehan thought that Jesus’ “doctrine of the kingdom meant that henceforth and forever God was present only in and as one’s neighbour” and that “Jesus dissolved the fanciful speculations of apocalyptic eschatology into the call to justice and charity” to that neighbour. In the face of Jesus so understood we begin to see the death of traditional religion and religion’s God and the beginning of something we can call the post-religious experience which is the abdication of “God” in favour of God’s hidden presence in our neighbour.]

I think that in European and North American liberal religious circles we have become seriously disconnected from this face and, therefore from a motivating, ethical demand. As communities we can, to be sure, point people inquiring about liberal religion to a broad canvas of purposes and principles which indicate what is in theory to be done as a liberal but what we are finding it increasingly difficult to do is to present an inquirer with a personal face in which they, and we, can see what is to be done as a religious liberal actually being done.

To illustrate what I mean let’s turn to the well-known story of the good Samaritan but, to see it working at its most powerful best, we need to recall that, once upon a time, it was common for most people to have in their homes, their Bibles, their churches or on their person (as I do) a ready-to-hand representation of the face of Jesus towards which they would always be able to turn either in fact or in memory.

[In passing but, I think, importantly, it has been well pointed out that thanks to critical historical scholarship we have been able to cut away much of the later Church's metaphysics and, therefore, in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries we are perhaps better able to catch a glimpse of the human face of Jesus than any of our Christian forebears.]

Reading the parable when this remains the case a person receives the story across the millennia from the face of Jesus, a real, historical human individual whom we know gave up his life in the cause of justice and the common good and whose example makes upon us the infinite ethical demand to “go and do likewise.” This face to face encounter with the human Jesus the social, religious and poetical activist, story-teller and teacher (rabbi) then demands we look at and listen to another face and infinite demand, namely that of the brutally beaten-up man lying injured by the road. As the story unfolds we are also enabled to look at and listen to yet another face and infinite demand in the good Samaritan who does not walk on by on the other side but responds as best and as lovingly as he can.

Nowhere in this story is any moral principle or purpose ever articulated, there is only this face then that and certain associated actions and infinite ethical demands which, to return to Critchley’s point, are powerfully experienced both when we respond generously to Jesus and the people he places before us and also when we choose to pass them by silently wishing they were somehow invisible and wincing internally at our callousness.

Naturally the Unitarian Universalist Association’s beautiful principles and purposes speak generally and approvingly about the kind of actions found in Jesus’ parable — how could they not! — but my point is that as principles and purposes they are abstract, second-order moral expressions — they do not present us with a human face in which, as we look into that person’s eyes, we can properly experience a truly motivating ethical demand to “go and do likewise.”

In our secular humanist context (and remember I personally have no choice but to speak as an atheist, albeit a Christian atheist) the only place where we can find what we have long called God is in the appeal directly experienced in face of the neighbour and it is this which primordially motivates us and which gives us “an image and a passion” — it is not found (I would argue) in the rational acceptance of abstract principles and purposes not matter how good, true and beautiful they may be.

Now I quite realise that you may well be able to make a good case that Jesus is not the face we in liberal religion need today. You may say his face has been too compromised by the many dreadful actions done in Jesus’ name by the Christian Church. Perhaps this is correct.

Personally speaking, all I can say is that the infinite demand found in his face is what inspired me as a child and it is the same face which still drives me to act in the world as a religious liberal in the ministry of a radical, liberal, free-thinking church community that had also answered the same infinite demand. (Here's a very brief piece of autobiography which may help make this paragraph make more sense.) I personally can't let this go - but that is not to say this church as a living tradition cannot begin to seek another face.

So, as I've just said, perhaps you are right and Jesus is no longer suitable as our corporate inspiring image and passion. But I still maintain that without an image and a passion tied to an actual human face our purposes and principles will continue to fail to be effective and persuasive and we will increasingly find ourselves in retreat before the many revanchist illiberal forces abroad in the world today.

And so I finish today’s address with the same plea I made last Sunday: “Get a model. Find a prototype. Without this there is no image and no passion” — and so no way to achieve a powerful and effective liberal religious life of your own.

Comments