Two Short Books by Margaret Barr (1899-1973): "The Universal Soul" and "The Great Unity"—A Unitarian interfaith educational pioneer

|

| Margaret Barr (aged about 20-21) |

Well, (apart from the Indian connections contained in two recent posts of mine HERE and HERE) she was in mind because I had recently got two of her books out to show them to a story-teller who is going to work with our children's church Sunday Club for a couple of weeks in the autumn and I wanted to introduce her to something of the open religious tradition of this particular Unitarian community and Margaret Barr remains such a splendid figure in our history that making the texts available for the story-teller proved irresistible.

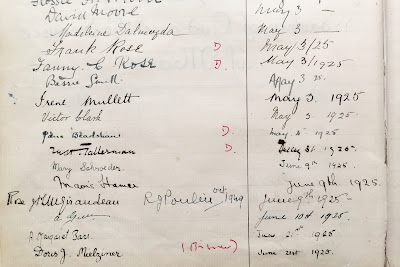

You see Margaret Barr became a Unitarian and member of the Cambridge Unitarian church (where I am minister) whilst studying at Girton College during the 1920s. Below, you can see her signature in our membership book (her's is the penultimate signature — just click on the photo to enlarge it).

|

| Margaret Barr's signature in the Cambridge Unitarian church membership book |

The two books of her's I have in my own library are, a copy of her early comparative religious educational book "The Great Unity" published in 1937 based on her curriculum for the non-sectarian "Gokhale Memorial Girls' School" in Calcutta (Kolkata) during 1933-1936, and a memorial volume called "Margaret Barr A Universal Soul" which was published in 1975 by the "Unitarian Inter-Faith Fellowship of India" shortly after she died.

So, for your interest, enjoyment and information I've put the scanned copies of the above books on the Cambridge Church website. Just click on the following links to download them:

Now, with this introduction out of the way here is the biographical piece about Margaret Barr I mentioned earlier. Enjoy!

REVEREND ANNIE MARGARET BARR (1899 – 1973)

EXCERPTS TAKEN FROM A BROCHURE “KHUBLEI” WRITTEN BY MARY LAWRENCE

EXCERPTS TAKEN FROM A BROCHURE “KHUBLEI” WRITTEN BY MARY LAWRENCE

Born in the year 1899 in England, Miss barr was appointed a Unitarian Minister for the Khasi Hills by the British General Assembly and Free Christian Churches, England. How she came to be appointed was an interesting story to be told. It was during her time of training for the ministry in England that Miss Barr came to know of a little Society called “The Friends of India” and of the cause of Indian freedom. It was then that she knew of Gandhi, studying his point of view and work, and eager to speak for his party.

Before long she was convinced that one who had never been to India did not carry conviction in her addresses – so her objective was to get to that sub-continent. Besides, she had a second motive for while when she was serving as pastor of Rotherham church, England, she learned for the first time of the little indigenous Unitarian movement in the Khasi Hills of Assam. The urge to go was strong, but there was no money in sight for the costly journey.

Four year later an opportunity to work in India came to Miss Barr when she was invited to teach in the Gokhale Memorial Girls School in Calcutta. In October 1933, she set sail, landing in Bombay. On her way East she stopped at Wardha where she was met by her sister who was one of Gandhiji’s village workers; thus, she had an early introduction to Gandhiji who advised her to “keep out of jail and find some constructive work to do.”

She found constructive work, indeed pioneer work. “The authorities of that school felt the need of some form of religious instruction, but as the school was strictly non- sectarian and included Hindus, Brahmos and Muslims it was clearly impossible to give sectarian instruction. It was decided to entrust the working out of a suitable scheme to one with a broad Universalist point of view - a method with genuine interest in and unbiased study of all the world’s great religious traditions. And this should be started at a very tender age by saturating the child’s mind with story material, not from one, but from all, till Christians are as familiar with the story of Buddha carrying the little lamb in his arms as they are with Jesus blessing the children, till Muslims know as much about Arjun’s conversion with God as they do about Mohammed’s childlike trust has been the outstanding characteristic of the religion of the world’s supreme spiritual master and is far more comprehensible to the child’s mind that to the average mature one. To teach only ethics and to withhold such things as these is to deny the children the very thing which they are most capable of entering into, and which will stand them in good stead later in the development of their religion. In the common denominator of all the great religions, this deeply spiritual teacher found “The Great Unity” – a title she employed for her book on the subject. Before long she was to find the same world outlook in the writings of Hajom Kissor Singh.

In the first vacation, Miss Barr made a trip to the Khasi Hills in June 1934. On her arrival she was accorded a special reception by the Khasi Unitarians and the women presented her with a gold ring. To the Khasi Unitarians, Miss Barr was like an answer to urgent prayers. For the love and affection, Khasi Unitrians called Miss Barr “Kong Barr”.

In the autumn of 1936, Kong Barr again came to Khasi Hills as the representative of the British General Assembly of Unitarian and Free Christian Churches. However, she delayed starting her active work until 1938 due to a trip back to England.

Immediately on arrival in Khasi Hills in 1938, Miss Barr joined her Unitarian people in their annual pilgrimage to the church chosen for the Union meetings, walking all the way since there were no other means than one’s bare feet. Her arrival was always acclaimed with shouts of Kong Barr. She and they bedded down on the floor for the two or three nights of the conference. Usually, the officers of the Union invited her to deliver the sermon, and she took advantage of this chance.

In another way Miss Barr could help the Union; she undertook an annual tour of the churches bringing them uplift and cheer, and strengthening them where they required it.

These were helpful acts; but there was a far more pressing matter confronting her, which she immediately took upon herself to attack, the illiteracy of the majority of the Khasi Unitarians. In her tour, it was starkly revealed. She made the following observations: -

Though only a small group, they have most of the things necessary for growth and progress – loyalty, enthusiasm, a simple and beautiful faith, left to them in clear and intelligible form by the genius of their founder, and few leaders who have caught his spirit. But, with very few exceptions, they are terribly poor, and in this country there is no education except for those who can pay for it. But without education how can a Unitarian church prosper?

Miss Barr faced a situation not to be found in any other part of the world, illiterate Unitarians; government schools were more than twenty years in the future.

As I met the same faithful few in the little churches, separated many of them by 18 or 20 miles from the nearest neighbor, and as I see all the rival churches with their schools and paid workers, still the wonders grow that this little courageous movement should have survived at all. That it has done so is largely due to the staunchness of those who came in during the time of the founder. But that generation is rapidly dying out – the generation of those who knew will arise. Something else must be put in the place of early youthful enthusiasm. I am not sure what something else will be but I feel it will come through education.

From then to the present work of Miss Barr has been in that field – a great contribution and a vital one for the survival of the Unitarian Churches. She began in Shillong, the Capital of the State, with an infant school and a teacher-training program. This was followed by a second training school in the same town. It was later that she went into the interior for the Rural Center. And since lack of money there was little or none, her pupils paid nothing.

She had the great advantage to be able to follow the pattern by Gandhi in his experimental teaching method at Sevagram. His village, like hers hundreds of thousands of Indian villages, was illiterate. The “Basic Education” that Gandhi developed was intended to start rural, undeveloped people on the path toward literacy and much more. The first task is to build up a cooperative, self-sufficient community. E.W. Aryanayakam: “A community that will produce its necessities in food, clothing, shelter and tools, not a process of production and commerce but an educational process for a balanced life; a community that will be able to meet many of its aesthetic, spiritual and intellectual needs, creating its own art, music, literature and drama, and above all a community where a man may be respected as a man and there will be no distinction of caste, class or creed; where all religions and faiths of mankind will be equally honored.”

Miss Barr’s enthusiasm for the Gandhian program increased with the years. Early in her work she sent one of her teachers-in-training to study Hindi and weaving and “pick up what she could of the Gandhian spirit; then when India became independent (1947) and everyone was “very Gandhi-minded, not only Assam but all the state governments of the country were introducing Basic Education in their schools in rural areas. A full-fledged Training Centre for Basic Education was developed at Sevagram. But it did not last long.” Miss Barr regretfully reports, “due to inertia and the active opposition of some old line educators and the initial mistake of having the training center in a town instead of in a rural area.” For this reason, Miss Barr left Shillong for Kharang village in the beginning of the1950’s and made Kharang her home away from home and when she had settled down, she started an orphanage school based on Gandhian ideals, and she lived up to those ideals till she breathed her last.

Comments

This article is awesomely great!

Thanks for writing and reminding me how much Kong Barr is still remembered and loved by your own community. Much appreciated. I try to keep her memory alive here in the Cambridge Unitarian Church, but it is clear that her real and lasting legacy is with you in Kharang. I hope that having access, at least, to two of her books in pdf form is helpful but I will write to you at your email address as requested.

Thank you, too, for your own article of a few years ago written for the UUA's International blog called "Indian Independence Day for Khasi Unitarians" which I very much enjoyed reading.

With the warmest of wishes,

Andrew