Creating a liberal, free religion appropriate for the possible incoming sea of faith

|

| The tide coming in below Copperas Woods on the River Stour at Wrabness, Essex |

A short “thought for the day” offered to the Cambridge Unitarian Church as part of the Sunday Service of Mindful Meditation

—o0o—

Much thinking about the future of religion in the UK has been done using the metaphor of the withdrawing tide used as it was used in 1867 by the poet and cultural critic, Matthew Arnold (1822–1888), in his famous poem “Dover Beach”, lines 21–28 of which read:

Was once, too, at the full, and round earth’s shore

Lay like the folds of a bright girdle furl’d;

But now I only hear

Its melancholy, long, withdrawing roar,

Retreating to the breath

Of the night-wind, down the vast edges drear

And naked shingles of the world.

There is no doubt that in the United Kingdom — and, indeed, in many European countries and the US — formal religious belief, especially Christian belief, has been in significant decline since the mid-nineteenth century. Consequently, the question long faced by a small, liberal Christian derived denomination such as the one to which I belong, has been how on earth are we to respond to the withdrawal of the sea of faith?

All the available evidence suggests we have not responded well and, denominationally speaking, we are now very, very close to extinction. The denomination’s last published annual report for the year 2021 reveals we have dipped below 3,000 members, that three-quarters of members and trustees are over 70, and that over half our 160 congregations now have fewer than 20 members. As the report says: “it’s clear we are at a critical moment.”

In one sense, therefore, we seem utterly to have failed to answer the question posed by the withdrawal of the sea of faith.

But, more and more, I’m wondering whether simply to say we have failed, and to leave it at that, is to look at the matter in the wrong way. This is because, if one is minded to continue to use Arnold’s metaphor of the tide — and I should add that the wisdom of doing this is not entirely clear to me — but, if one does continue to use it, then one needs to be alert to the truth that, as surely as night follows day, tides turn and the sea returns.

This leads me to ask whether, perhaps, the real task of the Cambridge church where I am the minister and the national denomination to which I belong will turn out to be, not the creation of a liberal, free-religion appropriate for the withdrawal of the sea of faith but, instead, to create one appropriate for the possible return of the sea of faith?

But this is to get ahead of myself.

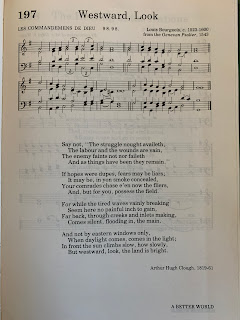

Firstly, it’s helpful and fascinating to know that Arnold’s friend and fellow poet, Arthur Hugh Clough (1819–1861) was way ahead of me here. We can see this in his poem (which has been set to music in one of our hymn books), “Say not the struggle naught availeth”:

|

| Click on photo to enlarge |

The labour and the wounds are vain,

The enemy faints not, nor faileth,

And as things have been they remain.

If hopes were dupes, fears may be liars;

It may be, in yon smoke conceal’d,

Your comrades chase e’en now the fliers,

And, but for you, possess the field.

Seem here no painful inch to gain,

Far back, through creeks and inlets making,

Comes silent, flooding in, the main.

When daylight comes, comes in the light;

In front the sun climbs slow, how slowly!

But westward, look, the land is bright!

Clough understood that in the midst of any struggle, the smoke and general confusion of action always hides from us any hope of being able to see the entire landscape around us or, indeed, of knowing whether one’s cherished hopes for a better future are real or simply delusional, mere dupes. However, Clough also saw that this means it is equally impossible to tell for sure whether one’s fears are also unfounded. It could be that, even though we truly feel the struggle for a better future has been lost, it may be that somewhere soon, out of sight, our comrades will have won and now possess the field.

To express this thought in another fashion, Clough also uses the tide metaphor. But, unlike Arnold, he employs it, not in the context of an exposed, pebbly and, therefore, often very noisy and dramatic beach like that at Dover as the tide withdraws, but in a less dramatic coastal landscape characterised by a complex of quiet creeks and inlets in which the tide is returning.

Although Clough starts the second half of his poem on a noisy and exposed open beach where, he notes, the tired waves appear vainly to be breaking and, painfully, they seem to gain not an inch, he immediately directs our imaginations back inland to those creeks and inlets where the water is, nevertheless, coming silent, flooding in. The point is that on these creeks and inlets as the tide turns there is no immediately obvious movement nor sound of return. Here, the turning of the tide is an extremely quiet and subtle event, the slow unfolding of which can easily be missed for a long, long time, even by the most careful observer.

Clough then notes how this is similar to the coming of dawn. As the sun slowly rises, the new day’s light arrives most obviously and dramatically through eastern windows. But, as he points out, this dawning light is always-already slowly and subtly being cast forward across the landscape so that when, eventually, westward we look, we find the land is now bright.

With this more nuanced metaphor of the tide in mind, let me now restate the thought I briefly expressed earlier.

As a liberal free-religious tradition we have clearly failed to provide an adequate religious response to the withdrawing sea of faith. Every measure available to us starkly reveals this. But what if this turns out not to have been our church’s real task? What if the withdrawal, and all the painful challenges it has brought us, were simply a necessary and vital preparation for us so we could play a meaningful part in the creation of a new kind of liberal, free-religion appropriate for the return of the sea of faith? A return of faith that is inevitably going to be both post-Christian and post-secular in character. [Ad-libbed addition in the service: “Please note that I said post-Christian and not anti- or non-Christian. This is, in my mind anyway, very much a continuation of Bonhoeffer’s religionless Christianity”] A faith which takes seriously, not only the mystical insights of our own Christian forbears and those of countless other non-Christian religious and philosophical teachers, but also the rational insights of the natural sciences. A new expression of faith that is, therefore, both religious and naturalist.

This is the hope that lay behind the creation, over a decade ago, of the evening service of mindful meditation which, during and now beyond the pandemic, became our morning service. This hope rests on an intuition I have that the main, that is to say, the sea of faith, is slowly and silently flooding in again.

Of course, back in the 2010s as now in the 2020s, I am forced to confess that, like Clough, I simply cannot see the whole field that makes up our present, confusing and extremely challenging situation, and my personal vision is, like everyone else’s, severely limited and confused by the thick, black smoke that is blowing everywhere about. All is not clear and so, as a passionate advocate for a modern, relevant, liberal, free-religion, I constantly, and often cripplingly, feel my hopes are dupes. And so they may be.

But, but, but . . .

Comments