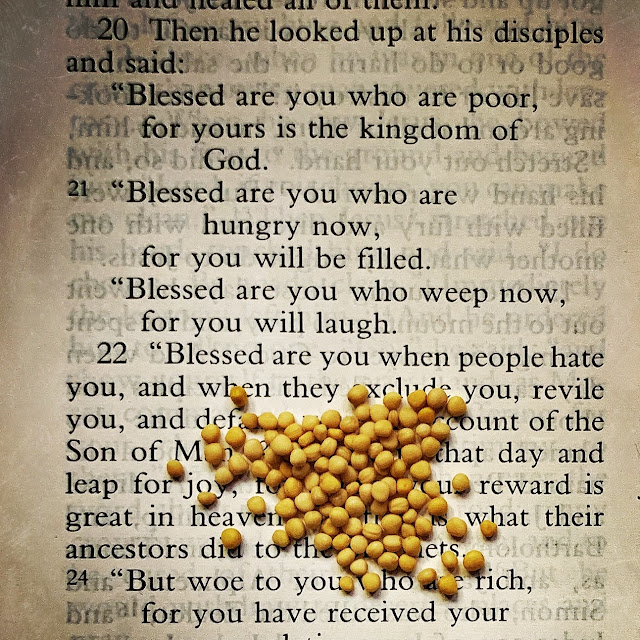

Tiny seeds and tiny words of love, freedom and justice. Scatter them. — Resisting the neoliberal onslaught

—o0o—

Jesus’ teaching — a teaching deeply rooted, remember, in the 8th-century Jewish prophetic tradition of Amos, Hosea, Isaiah and Micah — centres on the left-behind poor of his own time. Despite evidence to the contrary, he was able to proclaim, and live and die, by the belief that:

“Blessed are you who are poor, for yours is the kingdom of God. Blessed are you who are hungry now, for you will be filled. Blessed are you who weep now, for you will laugh” (Luke 6:20-21).

Alas, since Jesus’ day, evidence to the contrary has only continued to be gathered, so much so that the rich and powerful around the world continue to look down from their thrones — or today, perhaps from their Lulu Lytle designed sofas in some penthouse — and they have good reason to believe that the poor will never inherit the kingdom of God; those who are hungry will never be filled; those who weep now will never laugh. From their perspective, the jury seems to have come out in their favour and this enables them confidently to ignore Jesus’ parallel teaching in which he said:

“But woe to you who are rich, for you have received your consolation. Woe to you who are full now, for you will be hungry. Woe to you who are laughing now, for you will mourn and weep” (Luke 6:24-25).

In fact, so secure and utterly without woe remain the rich and powerful in our culture that, in the daily evening service of our state religion, without a scintilla of either awareness and/or irony, there is still said or sung the Magnificat, Mary’s “Song of Praise” which reads, in part, that God has scattered the proud in the thoughts of their hearts, brought down the powerful from their thrones, lifted up the lowly, has filled the hungry with good things, and sent the rich empty away.

So, today, in the face of all the evidence to the contrary, what are we to make of, and do with, Jesus’ words? Should we just abandon them all as arrant, idealistic nonsense and simply get down with the brutal neoliberal project along with people like Liz Truss, Kwasi Kwarteng, Suella Braverman and the Free Market think tanks at 55 Tufton Street?

No, of course not. But successfully to resist the wholesale attack on the poor, hungry and grief-stricken of our own time I remain convinced we need to access once again the radical and still undischarged energy contained in Jesus’ words.

In our current situation, one thing we need to see clearly and urgently address is the way formal religio-political structures have, again and again, succeeded in neutralising progressive and reformist forces by co-opting and domesticating their language to make it work for precisely the opposite cause.

This is done because Jesus’ language is dangerous; it really does threaten the hegemony of the rich and powerful. In fact, it’s so powerful and dangerous that it can’t now be got rid of — too many people know about it to do that — but it has been successfully suppressed, cooled and contained.

Think of nuclear fuel. It is so dangerous and capable of producing huge amounts of energy that it has to be contained inside a pressure vessel constantly cooled by water which is then placed inside a building-sized confinement shell. The teaching of Jesus — and, indeed, the intimately related Song of Mary and the words of the eighth-century prophets — is so dangerous it has to be put inside the pressure vessel of religious doctrines constantly cooled by lovely music and soothing prayers which are then placed inside a formal state religion, aka, a culture-sized containment shell. After all, one doesn’t want that kind of radical reformist stuff exploding all over the place does one! Good Lord, no!

Now, there is good evidence that Jesus knew about this kind of strategy and it explains, perhaps, the true import of his parable of the mustard seed, the common Christian interpretation of which is, itself, a great example of containment, cooling and neutralising. Christianity did this by making the story seem to be merely a platitudinous tale about growth in which small things become big things. So, before we go on, just to remind you, here’s the parable as it is found in Matthew 13:31-32:

“[Jesus] put before them another parable: ‘The kingdom of heaven is like a mustard seed that someone took and sowed in his field; it is the smallest of all the seeds, but when it has grown it is the greatest of shrubs and becomes a tree, so that the birds of the air come and make nests in its branches.’”

Now, the first thing you need to know, if you are to free this story and to tap its still undischarged energy, is that Pliny the Elder (23–79 AD), the first-century CE Roman author and naturalist, tells us something that was well-known in Jesus’ time:

“Mustard ... with its pungent taste and fiery effect is extremely beneficial for the health. It grows entirely wild, though it is improved by being transplanted: but on the other hand when it has once been sown it is scarcely possible to get the place free of it, as the seed when it falls germinates at once” (Natural History: 19.170-171).

You also need to know that in the Mishnah, a later, 3rd-century CE text which eventually came to form part of the Talmud, the authors tell us that because of its tendency to run wild the planting of mustard seed in a garden was forbidden in Jewish Palestine (Mishnah Kilayim 3:2).

What this means, as the New Testament scholar John Dominic Crossan notes, is that

“It is hard to escape the conclusion that Jesus deliberately likens the rule [or kingdom] of God to a weed.”

Crossan then goes on to say that it

“. . . is not just that the mustard plant starts as a proverbially small seed and grows into a shrub of three or four feet, or even higher, it is that it tends to take over where it is not wanted, that it tends to get out of control, and that it tends to attract birds within cultivated areas where they are not particularly desired. And that, said Jesus, was what the Kingdom was like: not like the mighty cedar of Lebanon and not quite like a common weed, but like a pungent shrub with dangerous takeover qualities. Something you would want only in small and carefully controlled doses — if you could control it” (John Dominic Crossan, ‘Jesus — A Revolutionary Biography’, Harper San Francisco 1994, pp. 64-66).

Let those with ears hear, and those with eyes see because the rich and powerful have never, and will never, want the mustard-seed-sized words of Jesus to be sown because, when they are, they really do have a tendency to run wild and take over. It’s not that his teaching is wrong or arrant nonsense, rather it is that we, the potential sowers of the seed, have not been scattering it as much, or as widely as we might.

So, here in the Cambridge Unitarian Church this morning, you have in your hands some mustard seeds and, in your hearts, you have some tiny words of love, freedom and justice. Scatter them.

Blessed are you who are hungry now, for you will be filled.

Blessed are you who weep now, for you will laugh.

Comments